- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

War Photographer Summary & Analysis by Carol Ann Duffy

- Introduction

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Download PDF

- Line-by-Line Explanations

The Full Text of “War Photographer”

“war photographer” introduction.

- Read the full text of “War Photographer”

“War Photographer” Summary

“war photographer” themes.

Apathy, Empathy, and the Horrors of War

Lines 13-15, lines 15-18.

- Lines 19-24

Trauma and Memory

Lines 11-12.

- Lines 13-18

The Ethics of Documenting War

Line-by-line explanation & analysis of “war photographer”.

In his dark ... ... in ordered rows.

The only light ... ... intone a Mass.

Belfast. Beirut. Phnom ... flesh is grass.

He has a ... ... seem to now.

Rural England. Home ... ... weather can dispel,

to fields which ... ... a nightmare heat.

Something is happening. ... ... a half-formed ghost.

He remembers the ... ... into foreign dust.

Lines 19-21

A hundred agonies ... ... for Sunday’s supplement.

Lines 21-22

The reader’s eyeballs ... ... and pre-lunch beers.

Lines 23-24

From the aeroplane ... ... do not care.

“War Photographer” Symbols

Photographs

- Line 2: “with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows”

- Line 7: “Solutions slop in trays”

- Lines 13-15: “A stranger’s features / faintly start to twist before his eyes, / a half-formed ghost”

- Line 19: “A hundred agonies in black and white”

“War Photographer” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- Line 2: “s,” “s,” “s”

- Line 4: “th,” “th”

- Line 5: “pr,” “pr”

- Line 6: “B,” “B,” “P,” “P”

- Line 7: “H,” “h,” “S,” “s”

- Line 8: “h,” “h,” “th”

- Line 9: “th”

- Line 13: “S,” “s,” “t,” “f”

- Line 14: “f,” “s,” “t,” “t,” “t”

- Line 16: “h,” “h”

- Line 17: “w,” “w,” “w”

- Line 20: “s”

- Line 21: “S,” “s”

- Line 22: “b,” “b,” “b”

- Line 6: “Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.”

- Lines 11-12: “to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet / of running children in a nightmare heat.”

- Line 6: “All flesh is grass.”

- Line 1: “I,” “i”

- Line 2: “o”

- Line 3: “o,” “o”

- Line 4: “ou,” “e,” “u,” “e”

- Line 5: “ie,” “a”

- Line 6: “e,” “a,” “e,” “e,” “a”

- Line 8: “i,” “i,” “i,” “e,” “e”

- Line 10: “i,” “i,” “ea,” “e”

- Line 11: “ie,” “o,” “o,” “ea,” “ee”

- Line 13: “i,” “i,” “i,” “a,” “e,” “u”

- Line 14: “ai”

- Line 15: “ie”

- Line 16: “i”

- Line 17: “o,” “o,” “a,” “o,” “o,” “u”

- Line 18: “oo,” “u”

- Line 19: “a,” “a,” “a”

- Line 20: “i,” “i,” “i,” “i,” “i,” “i”

- Line 21: “u,” “u,” “i”

- Line 22: “i,” “ea,” “ee,” “e,” “ee”

- Line 23: “a,” “a,” “a,” “e”

- Line 24: “i,” “i”

- Line 6: “Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All”

- Line 7: “do. Solutions”

- Line 8: “hands, which”

- Line 9: “now. Rural England. Home”

- Line 13: “happening. A”

- Line 15: “ghost. He”

- Line 16: “wife, how”

- Line 21: “supplement. The”

- Line 1: “r,” “r,” “n,” “ll,” “l,” “n”

- Line 2: “s,” “l,” “s,” “s,” “t,” “t,” “r,” “d,” “r,” “d,” “r”

- Line 3: “l,” “l,” “l,” “l”

- Line 5: “pr,” “pr,” “p,” “r,” “t,” “t,” “ss”

- Line 6: “B,” “s,” “t,” “B,” “t,” “P,” “n,” “P,” “n,” “ll,” “l”

- Line 7: “H,” “h,” “S,” “l,” “sl”

- Line 8: “h,” “s,” “h,” “s,” “t,” “t,” “th”

- Line 9: “th,” “R,” “r,” “g,” “g,” “n”

- Line 10: “n,” “p,” “n,” “w,” “p,” “l,” “w,” “d,” “p,” “l”

- Line 11: “l,” “d,” “d,” “pl,” “d,” “th,” “th”

- Line 12: “n,” “n”

- Line 13: “S,” “str,” “r,” “s,” “t,” “r,” “s”

- Line 14: “f,” “t,” “st,” “t,” “t,” “t,” “st”

- Line 15: “f,” “f”

- Line 16: “w,” “h,” “w,” “h”

- Line 17: “w,” “w,” “d,” “d,” “w,” “eo”

- Line 18: “d,” “st,” “d,” “d,” “st”

- Line 21: “S,” “s,” “s,” “s,” “r”

- Line 22: “t,” “rs,” “b,” “tw,” “th,” “b,” “th,” “r,” “b,” “rs”

- Line 23: “s,” “r,” “ss,” “r”

- Line 24: “r,” “s,” “s”

End-Stopped Line

- Line 2: “rows.”

- Line 3: “glows,”

- Line 5: “Mass.”

- Line 6: “grass.”

- Line 10: “dispel,”

- Line 12: “heat.”

- Line 14: “eyes,”

- Line 18: “dust.”

- Line 22: “beers.”

- Line 24: “care.”

- Lines 1-2: “alone / with”

- Lines 4-5: “he / a”

- Lines 7-8: “trays / beneath”

- Lines 8-9: “then / though”

- Lines 9-10: “again / to”

- Lines 11-12: “feet / of”

- Lines 13-14: “features / faintly”

- Lines 15-16: “cries / of”

- Lines 16-17: “approval / without”

- Lines 17-18: “must / and”

- Lines 19-20: “white / from”

- Lines 20-21: “six / for”

- Lines 21-22: “prick / with”

- Lines 23-24: “where / he”

- Line 2: “spools of suffering”

- Line 6: “All flesh is grass”

Parallelism

- Lines 10-11: “to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel, / to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet”

- Lines 16-18: “how he sought approval / without words to do what someone must / and how the blood stained into foreign dust.”

- Lines 4-5: “as though this were a church and he / a priest preparing to intone a Mass.”

“War Photographer” Vocabulary

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- "All flesh is grass"

- Sunday's supplement

- Impassively

- (Location in poem: Line 1: “dark room”)

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “War Photographer”

Rhyme scheme, “war photographer” speaker, “war photographer” setting, literary and historical context of “war photographer”, more “war photographer” resources, external resources.

"War Photographer" Read Aloud — Listen to the poem read aloud.

Trailer for the Documentary "War Photographer" — Watch the trailer for the 2011 documentary War Photographer, which explores the responsibilities of photographers in war zones, focusing on photographer James Nachtwey.

"The Terror of War" — Explore Nick Ut's image from the Vietnam War, "The Terror of War." This famous photograph may have inspired "War Photographer." Note the second photographer at the right of the image examining his camera as children run by him, burnt and naked.

Carol Ann Duffy Biography — Learn more about Carol Ann Duffy, Britain's first female Poet Laureate, on Poets.org.

Interview with War Photographer Nick Ut — Watch this NBC interview with Vietnam War photographer Nick Ut about taking his famous photo depicting the naked "Napalm Girl" and the responsibility of photographers in war zones. Ut's comments intersect potently with the themes explored in "War Photographer."

LitCharts on Other Poems by Carol Ann Duffy

A Child's Sleep

Anne Hathaway

Before You Were Mine

Death of a Teacher

Education For Leisure

Elvis's Twin Sister

Head of English

In Mrs Tilscher’s Class

In Your Mind

Little Red Cap

Mrs Lazarus

Mrs Sisyphus

Pilate's Wife

Pygmalion's Bride

Queen Herod

Recognition

Standing Female Nude

The Darling Letters

The Dolphins

The Good Teachers

Warming Her Pearls

We Remember Your Childhood Well

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

- October 11, 2022

- All Poems / GCSE AQA

War Photographer, Carol Ann Duffy

FULL POEM - SCROLL DOWN FOR LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

In his dark room he is finally alone with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows. The only light is red and softly glows, as though this were a church and he a priest preparing to intone a Mass. Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.

He has a job to do. Solutions slop in trays beneath his hands, which did not tremble then though seem to now. Rural England. Home again to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel, to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet of running children in a nightmare heat.

Something is happening. A stranger’s features faintly start to twist before his eyes, a half-formed ghost. He remembers the cries of this man’s wife, how he sought approval without words to do what someone must and how the blood stained into foreign dust.

A hundred agonies in black and white from which his editor will pick out five or six for Sunday’s supplement. The reader’s eyeballs prick with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers. From the aeroplane he stares impassively at where he earns his living and they do not care.

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

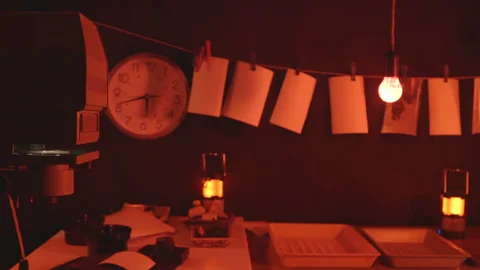

In his dark room he is finally alone

Duffy immediately creates a dark, somber tone by immediately setting the scene in the photographer’s ‘dark room’. A darkroom is used to process light-sensitive photographic film to develop photographs, hence would be how a photographer would publish their photos prior to the digital age. So here in a literal sense, the poem’s subject, the war photographer, is back home developing the photos he’s amassed from war. Figuratively, this tranquil setting juxtaposes the violence of the battlefields where he would have taken his photos, enabling a time for reflection – inevitably traumatic and depressing in nature for which the darkness is a metaphor.

with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.

The photographer winds his photographic film into ‘speels of suffering’ – a metaphor that portrays the sheer brutality of war captured in his photos. The sibilance in this line further emphasises this, resulting in a sinister hissing sound when spoken which is onomatopoeic for the hissing of shells and bullets on a battlefield.

The only light is red and softly glows as though this were a church and he a priest preparing to intone a Mass.

Duffy compares the dark room to a church through the simile ‘as though this were a church’ and the photographer to a priest through the metaphor ‘and he a priest preparing to intone a Mass’. The imagery of the red light that ‘softly glows’ supports this comparison. Red light is the only light source present in dark rooms to prevent damage to the photographic film and the overexposure of photographs. Meanwhile, in a church, it is also normally the colour of a sanctuary or altar lamp in the Christian tradition. The way in which the photographer prepares the photos of the victims is ritualistic, akin to a priest conducting a funeral. However, unlike how a priest is preparing to lay the dead to rest, the photographer is preparing for them to be published in newspapers – a contrast that makes the reader question the humanity of his profession.

Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.

The list of places of conflict, ‘Belfast.Beirut.Penh’ that he has photographed is an example of asyndeton – a list without conjunctions that here is instead punctuated with full stops. Such caesura reflects the photographer’s troubled pause for reflection as he prepares photos from each setting and allows the reader to do the same. ‘All flesh is grass’ is a biblical reference, here signifying how fragile and temporary life is especially in times of conflict, perishing and replenishing just like grass with the seasons.

He has a job to do. Solutions slop in trays beneath his hands, which did not tremble then though seem to now. Rural England. Home again

The abruptness of the opening to this stanza mirrors the photographer snapping back to reality and the job at hand, having become distracted pondering the trauma he has witnessed. Duffy also explores the irony between the photographer’s conduct when on the battlefield and when at home in ‘Rural England’. To work professionally at war, he must remain emotionally detached from his subjects, hence there’s a callous efficiency that the job entails. When at home though, a pause in the chaos of war results in the opportunity for its traumas to catch up with and consume him, leading to his hands trembling as he prepares the photographs even though they didn’t when he captured them.

to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel,

‘Ordinary pain’ is an oxymoron, emphasising the insignificance of the so-called ‘first-world problems’ experienced by those living in ‘Rural England’ compared to the problems of those living in ‘Belfast, Beirut, Phnom Penh’ and other war torn countries the photographer has worked in.

to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet of running children in a nightmare heat.

This rhyming couplet that concludes this stanza captures the brutality of the conflicts that he is reflecting upon by referencing the heartbreaking ‘Napalm Girl’ photograph depicting nine-year old Phan Thi Kim Phúc fleeing from a South Vietnamese air strike in 1972.

Something is happening. A stranger’s features

Duffy opens this third stanza abruptly with a short sentence, like the last. Here the effect is to create suspense as the caesura results in a pause in the narrative that leaves the reader hanging on what the ‘something’ that is happening actually is.

faintly start to twist before his eyes, a half-formed ghost. He remembers the cries

The imagery used to describe the development of this particular photograph is animalistic – the use of the word ‘twist’ evokes the image of a wounded animal writhing in pain, used to capture the agony of the ‘half-formed ghost’ (a metaphor for the dying man that describes he’s closer to dying than living) in the photograph.

of this man’s wife, how he sought approval without words to do what someone must and how the blood stained into foreign dust.

These lines explore the morality of the photographer’s profession. A dying man lies on the ‘blood stained’ ground beneath him, whilst the man’s wife cries in desperation as she loses him. Meanwhile, the photographer is a passive spectator, unable to offer help to the man or his wife, instead, he’s more of an intruder in their last moments together. His motive isn’t to cure the suffering but photograph and document it and in the moment that seems selfish, as though he is using it for his own gain. This, in part, is true – the more vivid and poignant the suffering that he captures is, the more successful he and his work become. But on the flip side, these are stories that need to be told, people at home, politicians, need to be made aware of these devastating conflicts if they’re ever going to end and the photographer is putting himself in the firing line to document these stories and one could argue that you don’t get less selfish than that.

A hundred agonies in black and white from which his editor will pick out five or six for Sunday’s supplement. The reader’s eyeballs prick

The final stanza describes the destination and purpose of the photographs that depict ‘a hundred agonies in black and white’. The term ‘a hundred agonies’ emphasises the scale of suffering that the photographer has captured and accumulated from country to country. ‘Five or six’ of the most shocking are then selected and published ‘for Sunday’s supplement’, designed to make as profound an impression on the reader as possible. As touched on previously, herein lies the debate on the morality of such publications.

with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers. From the aeroplane he stares impassively at where he earns his living and they do not care.

Having considered those who were the subject of his photographs, the photographer shifts his attention to those consuming them, the people back home in England who enjoy a much safer and easier life in comparison. How their ‘eyeballs prick with tears’ connotes how they are moved briefly but not sincerely by the photographs, akin to the momentary feeling of pain of pricking one’s finger, which subsides quickly at the thought of ‘pre-lunch beers’. The internal rhyme between ‘tears’ and ‘beers’ lightens the tone – further emphasising the shallow, temporary impact the photographs have on the readers. The poem concludes with the photographer coming to this realisation about his audience as he travels by plane most likely to his next place of work and no doubt this leaves him questioning the purpose and morality of his profession as he prepares to do it all over again.

You Might Also Like

Half-Caste, John Agard Poem Analysis/Annotations

The Manhunt (Laura’s Poem), Simon Armitage Poem Analysis/Annotations

- GCSE Edexcel

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

GCSE Poetry Comparison: War Photographer and Poppies Sample Essay

Welcome back to our series on the AQA Power and Conflict anthology—your go-to guide for writing comparative poetry essays!

In AQA GCSE English Literature , poetry comes toward the end of the exam, as part of Paper 2. By this point, you’ve already tackled a modern text you’ve prepared for and a daunting unseen section.

Then, you’ve got to analyse two anthology poems and compare them. It’s a lot to handle, and by this stage, you’ll be feeling tired. That’s why anything you can do to prepare will be a huge help!

With this in mind, we’re diving into comparative essays for every poem in the AQA anthology . We’ll break down key points, quotes and analysis, so you can be fully prepared to write a standout essay.

Today, we’re comparing War Photographer by Carol Ann Duffy and Poppies by Jane Weir. These are two of the most popular poems, as they’re written in a modern style with a powerful emotional impact. But do they have much in common beyond their strong messages?

Check out this sample essay comparing the two. As you read, get your mark scheme ready and think critically. Consider your own feelings and responses to the poems. What extra points or quotes would you add to make it even stronger?

In “War Photographer” by Carol Ann Duffy, the poet explores ideas about inner conflict. Compare this with “Poppies” by Jane Weir.

In “War Photographer” by Carol Ann Duffy and “Poppies” by Jane Weir, both poets explore inner conflict, focusing on how war impacts those left behind or who bear witness. Duffy portrays the moral struggles of a war photographer processing the horrors he’s captured. On the other hand, Weir delves into a mother’s grief and anxiety as her son goes to war. Both use vivid imagery and thoughtful structure to convey the deep psychological effects of war, though the nature of their inner conflicts differ significantly.

Duffy’s “War Photographer” examines a photographer managing the chaos of war through his work. The darkroom becomes a metaphor for his mind, where he confronts the images he’s captured: “spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.” This imagery contrasts the need for control with the overwhelming nature of war. The alliteration in “spools of suffering” adds a sinister undertone to the scene, while the later image of a “half-formed ghost” highlights the way memories and traumas still haunt him.

In contrast, “Poppies” presents a mother’s personal battle as she prepares to send her son to war. The opening, “Three days before Armistice Sunday / and poppies had already been placed / on individual war graves,” blends remembrance with foreshadowed loss, suggesting her awareness of what could come. While Duffy’s imagery evokes distant conflict, Weir’s use of domestic detail, pinning “crimped petals” onto her son’s blazer, brings the reader closer to the intimate pain of loss. The contrast between the mother’s care and the violence her son may face is heightened by the phrase “spasms of paper red,” subtly alluding to war wounds.

Both poets emphasise inner conflict through form. Duffy’s regular structure reflects the photographer’s methodical attempts to process his emotions. The tension between order and chaos mirrors the contrast between the structured form and the photographer’s inner turmoil. The poem shifts when the photographer realises the public’s detachment from his work, their emotions fleeting: “The reader’s eyeballs prick / with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers.” This emphasises his isolation, deepening his internal struggle as his experiences are dismissed.

In contrast, Weir uses a free-verse structure reflecting the unpredictability of the mother’s emotions. The lack of consistent rhyme or stanza length mirrors the chaotic flow of her thoughts as she wrestles with fear and pride. Weir’s enjambment, particularly in lines like “I resisted the impulse / to run my fingers through the gelled / blackthorns of your hair,” captures the fluidity of her emotional state, contrasting sharply with Duffy’s more rigid form.

Contextually, both poets come from different perspectives. Duffy, as poet laureate, often explores political and social issues, using “War Photographer” to highlight the emotional toll on those who document suffering. She challenges readers to consider the distance between war’s reality and their perception. Weir, drawing on personal experience, focuses on the intimate pain of a mother’s sacrifice. Her poem speaks to the personal costs of war, contrasting Duffy’s more external focus on media and societal detachment.

In conclusion, while both “War Photographer” and “Poppies” explore the inner conflict caused by war, they approach it from different angles. Duffy’s focus on the emotional struggle of documenting war contrasts with Weir’s intimate portrayal of a mother’s grief and anxiety. Together, they provide a powerful commentary on the psychological scars war leaves behind, highlighting the inner battles fought by those affected by it.

What are your thoughts on the essay and how the poems are compared? How do you feel about the two poems? Is there anything you’d include, change or something you’d disagree with? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

Support my work

Have you found this post helpful? By making a contribution, you’ll help me create free study materials for students around the country. Thank you!

If you like this, please share!

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

2 thoughts on “ GCSE Poetry Comparison: War Photographer and Poppies Sample Essay ”

Great work thank you!

Thank you very much Tom. I’m glad you’ve found it useful!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

War Photographer | Summary and Analysis

Critical appreciation of war photographer by carol ann duffy.

War Photographer by Carol Ann Duffy is a brief-yet-insightful poem that provides a touching perspective into the agonies of war, internal struggle, ethics, trauma and ignorance. Published by Carol Ann Duffy in 1985, War Photographer is a poem written in third-person. It depicts a photographer who has returned to his hometown to develop his photographs, all of which were taken at a warzone. Duffy captures it beautifully through the process of developing photos, rather than that of taking them. This adds to the emotion of the piece -in the dark room, the photographer is not required to remain as rational as he was on the battlefield. He lets his feelings sink in, even if it is just for a moment, and we are hence able to witness his internal struggle between professionalism and empathy. It also allows a calmer, less adrenaline-filled view on the topic of ethics in war photography, as compared to if the narrative had been during the war. The poem flows effortlessly, from the setting of context to the pain of war, to the traumatic memories and finally to the unfortunate ignorance of the public, encompassing a broad range of themes within four simple stanzas. Duffy’s distinct writing style aids this- she uses similes, metaphors, and imagery. She also inserts anticipation-inducing phrases at the start of her stanzas, which induce a sense of tense curiosity in her readers.

War Photographer | Summary

The poem starts with the photographer – referred to as ‘he’ throughout the text- alone in a dark room, with his yet-to-be-developed photographs set in front of him in orderly rows. One must keep note of the idea of namelessness and anonymity war had brought to the photographer concerned. There is no other light besides a soft red glow , which makes the photographer feel as though he is attending a Mass at church. The names of warzones cross his mind, making him think that in the end, everyone who dies returns to the same soil.

In the next stanza, we see that the photographer has a task at hand- developing his film. He holds a tray of solution in his hands- oddly enough, his hands, which did not tremble while taking the pictures at the warzone, tremble now . We learn that he is in Rural England, his hometown- a place where his suffering is minimal and his mood can be improved by simply the weather, where there are no bomb blasts and explosions within the sprawling fields, and where no children run in panic in an attempt to flee the scene of war,

A stranger’s features start appearing faintly, still translucent as the film continues to develop. When the photographer sees the man’s face, he remembers the moment he took the photo – the way the man’s wife cried, the way he wordlessly and quickly sought approval before taking the photo, and the way the man bled to death on foreign ground.

As the photos- hundreds of them- continue to develop in black-and-white, the photographer thinks of them as agonies. He knows that the editor of the magazine will pick only a few to publish in the Sunday supplement, and that the readers will s hake their heads with tears in their eyes , momentarily emotional in the late morning. As the photographer sits in the airplane, staring out the window and down at the warzones where he had taken so many photos, he knows that none of them truly care about where the images came from.

War Photographer | Analysis

War photographer | analysis, stanza 1.

In his dark room he is finally alone with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows. The only light is red and softly glows, as though this were a church and he a priest preparing to intone a Mass. Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.

In the first stanza, the rows of film are described as “ spools of suffering ” which is the first hint of the nature of the photos. The photographer is left anonymous , which may hint at the distance between him and the true cruelties of war. After all, he is able to leave when he wants to, not having to endure the same pain as those within the war. He is, at the same time, not completely ignorant to its horrors as the rest of the public, who have never witnessed it first-hand. He lies midway, an outsider in both worlds – this element is emphasized by his namelessness in the poem. When he likens the soft red glow of light to the Mass at church, he imagines the words, “Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. ”, all of which are badly hit warzones. The line “All flesh is grass. ” refers to the way war often ends with death. The body decays and joins the soil, e veryone enters the earth once more.

War Photographer | Analysis, Stanza 2

He has a job to do. Solutions slop in trays beneath his hands, which did not tremble then though seem to now. Rural England. Home again to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel, to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet of running children in a nightmare heat.

The suddenness of the line “He has a job to do .” is an example of Duffy’s anticipation-inducing inserts . It jolts the readers from hazy imagination to reality , and this abrupt transition is symbolic of the emotional switch the photographer must exhibit during his job- between sadness and empathy for those wounded in war, and responsibility and focus on his task. However, the fact that “ his hands, which did not tremble then though seem to now ” shows that he is n ot quite able to shake off the intensity of his thoughts and memories. While he remained calm on the scene of the war, the recollection of the moments causes him to shake. This also hints at him being nervous to see the fully-developed photos, possibly afraid of reliving those moments . Duffy also employs the juxtaposition of the bomb-blasted warzones versus the serenity of Rural England . This provides an illustrious imagery of just how different life on the warfield is, and ties into the previous point of the photographer being able to escape the reality of war , unlike those who die there. The “ ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel ” describes just how normal life in Rural England is, where one’s suffering halts just because of pleasant weather. The “nightmare heat .” in the last line is the heat from the fire caused by the explosions.

War Photographer | Analysis, Stanza 3

Something is happening. A stranger’s features faintly start to twist before his eyes, a half-formed ghost. He remembers the cries of this man’s wife, how he sought approval without words to do what someone must and how the blood stained into foreign dust.

“Something is happening ” is another phrase employed to stir anxiousness and tenseness in the readers, leaving them in suspense . The photographer calls the stranger’s appearing features a “ half-formed ghost” which implies that the photo is still translucent and developing- the word “ ghost” also emphasises the eerie nature of the photographs. It is important to note that the man in the image is simply called “ stranger ”, for the photographer d oes not know his name – he is just one of the many who died on that foreign ground. This is an almost sad realisation, as life is a precious thing. Yet while documenting it’s cruel end, there was not even enough time or means in the terrible situation for the photographer to learn the name of the dying man in his own photograph. It represents the fleeting nature of life , especially in war. Lives slip away in the blink of an eye, too many people to name.

The photographer remembers three things most clearly from that moment: “ remembers the cries of this man’s wife, how he sought approval without words to do what someone must and how the blood stained into foreign dust .” The cries of the man’s wife portray the agony of the ones being left behind – the families who lost loved ones and watch them pass right before them, while the photographer’s seeking of approval before taking the photo portrays the i nternal conflict of war photography ethics . The ethical side will ask, is it morally right to take pictures of someone’s gruesome last moments, and of their family’s grief? Is it right to use the images to earn money and print in magazines for the country to see? While the professional side may argue that it is simply part of the job, that permission has been received. And the final part about the man’s blood staining foreign ground highlights the way he was not even able to die in the warmth and comfort of his own country – he will become one with the soil of a foreign country, instead.

War Photographer | Analysis, Stanza 4

A hundred agonies in black and white from which his editor will pick out five or six for Sunday’s supplement. The reader’s eyeballs prick with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers. From the aeroplane he stares impassively at where he earns his living and they do not care.

“A hundred agonies in black and white ” represents the various traumatic photos that the photographer has captured. The use of the word ‘agonies’ suggests that despite maintaining his professionalism , that tinge of sadness will always remain – the pain of seeing such ruthlessness may be ignored while working, but cannot be forgotten . It is then mentioned that the editor will “ pick out five or six for Sunday’s supplement.” After all, these photos are for publishing . But after reading the previous three stanzas, it creates a disturbing feeling, realising that out of hundreds of heartbreaking, cruel tragedies, the editor will simply pick a few and discard the rest as though they do not matter. He will likely choose the most ‘aesthetic’ ones which fit the magazine, or the most horrifying ones which are certain to draw attention . There is a sense of discomfort at how people’s suffering and torture is used for commercialism.

When the magazine is published, “ The reader’s eyeballs prick with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers.” The important point here is the specified timestamp . “Between the bath and the pre-lunch beers ” suggests that it is around late morning that they will see the photos. They will feel emotional for a brief moment while reading , and will move on as soon as they put the magazine down. This is a privilege that does not exist for those trapped in war- similar to the comparison between Rural England and warzones. The readers have the luxury of seeing and forgetting, feeling momentary sympathy and nothing more.

The last line of the poem shows the photographer: “f rom the aeroplane he stares impassively at where he earns his living and they do not care.” He is flying somewhere, likely the next location for his jo b, another warzone to take pictures at. As he looks down at the warzones, the use of the word “impassive” represents the necessary switch between emotional and professional. While he spent quite a lot of time feeling upset, he realises as he sees the warzones again that he will soon need to return to his goal-oriented self. His lack of emotion portrays the way he steels himself for what is to come . The ending of the poem- “they do not care” – refers to both his editors and the public who read the magazines and see the photos. Their consumption is merely entertainment for them. They are ignorant to the brutality of the warzones, the internal struggle of the job. They do not think about the families of the people they see in the pictures, or wonder what is going on now in the warzones. It does not matter to them, because they are removed from the situation. They view the photos and shake their heads in sympathy, and calmly move on with their own lives.

Hiroshima by John Hersey | Summary and Analysis

The marble champ | summary and analysis, related articles.

The Darkling Thrush | Summary and Analysis

Analysis of in a london drawingroom.

The Tell-Tale Heart Summary and Analysis

Summary of the bass the river and sheila mant, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Adblock Detected

Ms Bellamy's English Class blog

'war photographer' notes, example essay and revision/essay-writing tasks.

- The subject(s) of the poem

- The attitude of the poet

- The poetic devices the poet uses

it is very accurate and it helped me in my english class

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The best War Photographer study guide on the planet. The fastest way to understand the poem's meaning, themes, form, rhyme scheme, meter, and poetic devices.

£Ðÿ QUë! } h¤,œ¿?B†¹/S}ÿì\N;H‘4! ŠêŒéô"§þâY K 6 ð K•øi²©ýŸ® ½_šI `'f&NivZ»h*% `ìüÿÛ¯>ån@ÔÑls¢ Œ¨º÷‰†Ï½ ªnÕ ...

Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘War Photographer’ depicts the poet’s opinions toward society and the agonies of war, in addition to the lack of interest of mankind toward it. Moreover, Duffy wrote the ‘War Photographer’ inspired by his friendship with Don McCullin and Philip Jones Griffiths. Both of them were well-respected stills photographers ...

Apr 30, 2024 · Published in 1985, 'War Photographer' depicts the solitary experience of a photographer at home in England developing photographs taken in conflicts around the world. The poem comments on the personal distress of the photographer at what they have seen in warzones, and how people back home respond. ‘War Photographer’ analysis. Lines 1-2

Oct 11, 2022 · The photographer winds his photographic film into ‘speels of suffering’ – a metaphor that portrays the sheer brutality of war captured in his photos. The sibilance in this line further emphasises this, resulting in a sinister hissing sound when spoken which is onomatopoeic for the hissing of shells and bullets on a battlefield.

Published in 1985, War Photographer explores the impact of the media and images that are produced of war. At the time of publishing this poem in 1985, the Vietnam War had finished a decade previously, the Troubles raged on in Northern Ireland, Lebanon was in the middle of a civil war, and Cambodia had experienced brutality on an enormous scale.

Sep 21, 2024 · With this in mind, we’re diving into comparative essays for every poem in the AQA anthology. We’ll break down key points, quotes and analysis, so you can be fully prepared to write a standout essay. Today, we’re comparing War Photographer by Carol Ann Duffy and Poppies by Jane Weir. These are two of the most popular poems, as they’re ...

Aug 23, 2022 · War Photographer by Carol Ann Duffy is a brief-yet-insightful poem that provides a touching perspective into the agonies of war, internal struggle, ethics, trauma and ignorance. Published by Carol Ann Duffy in 1985, War Photographer is a poem written in third-person. It depicts a photographer who has returned to his hometown to develop his ...

Oct 9, 2023 · Stanza-by-Stanza Analysis 'War Photographer' has a third-person speaker, someone who is 'looking in' on the photographer as he develops his latest images in the darkroom. This is the traditional way of bringing images out into the world (which may seem strange in this modern digital age), using liquid chemicals and photographic paper.

The surface subject of the poem is the war photographer of the title but at a deeper level the poem explores the difference between "Rural England" and places where wars are fought (Northern Ireland, the Lebanon and Cambodia), between the comfort or indifference of the newspaper editor and its readers and the suffering of the people in the ...