Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Mr. E.A. is a 40-year-old black male who presented to his Primary Care Provider for a diabetes follow up on October 14th, 2019. The patient complains of a general constant headache that has lasted the past week, with no relieving factors. He also reports an unusual increase in fatigue and general muscle ache without any change in his daily routine. Patient also reports occasional numbness and tingling of face and arms. He is concerned that these symptoms could potentially be a result of his new diabetes medication that he began roughly a week ago. Patient states that he has not had any caffeine or smoked tobacco in the last thirty minutes. During assessment vital signs read BP 165/87, Temp 97.5 , RR 16, O 98%, and HR 86. E.A states he has not lost or gained any weight. After 10 mins, the vital signs were retaken BP 170/90, Temp 97.8, RR 15, O 99% and HR 82. Hg A1c 7.8%, three months prior Hg A1c was 8.0%. Glucose 180 mg/dL (fasting). FAST test done; negative for stroke. CT test, Chem 7 and CBC have been ordered.

Past medical history

Diagnosed with diabetes (type 2) at 32 years old

Overweight, BMI of 31

Had a cholecystomy at 38 years old

Diagnosed with dyslipidemia at 32 years old

Past family history

Mother alive, diagnosed diabetic at 42 years old

Father alive with Hypertension diagnosed at 55 years old

Brother alive and well at 45 years old

Sister alive and obese at 34 years old

Pertinent social history

Social drinker on occasion

Smokes a pack of cigarettes per day

Works full time as an IT technician and is in graduate school

- Register-org

- Subscriptions

Recent Posts

- 7 Health And Wellness Products To Have In Your Winter Essentials

- How Can You Enhance Your Overall Health This Winter Season?

- Dermatologist Austin TX: Skin Care Tips Revealed

- Future Trends in Dentistry: What Dental Professionals Need to Know

- The Role of Kaizen in Enhancing Healthcare Efficiency

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

- Allergy and Immunology

- Anesthesiology

- Basic Science

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Cardiovascular

- Complementary Medicine

- Critical Care Medicine

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Hematology, Oncology and Palliative Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Medical Education

- Neonatal – Perinatal Medicine

- Neurosurgery

- Nursing & Midwifery & Medical Assistant

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Opthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Otolaryngology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Plastic Reconstructive Surgery

- Pulmolory and Respiratory

- Rheumatology

Search Engine

Hypertension (Case 7)

Published on 24/06/2015 by admin

Filed under Internal Medicine

Last modified 24/06/2015

This article have been viewed 6928 times

Elie R. Chemaly MD, MSc and Michael Kim MD

Case: A 59-year-old African-American woman is referred by her primary physician. She has had a history of severe hypertension for 38 years. She complains of dizziness, occipital headaches with blurred vision, and palpitations correlated with high BP sometimes reaching 200 mm Hg systolic and 120 mm Hg diastolic. She also has claudication of the legs and thighs upon walking four street blocks. She has a history of thyroid disease and is presently hypothyroid. Her medications on presentation were valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide 320 mg/25 mg (one tablet daily in the morning), clonidine 0.3 mg (one tablet daily in the evening), verapamil SR 240 mg (one tablet twice a day), and levothyroxine 0.1 mg (one tablet daily). Although she takes her medications each day as directed, she confides to you that she is concerned that they are becoming increasingly difficult for her to afford on a limited budget. She has an extensive family history of hypertension, and her father died at the age of 57 years in his sleep. On examination she weighs 68 kg, her pulse is 60 bpm, and her BP is 148/88 mm Hg. Her examination is remarkable for bilateral femoral bruits.

Differential Diagnosis

Speaking Intelligently

The first assessment when approaching the hypertensive patient is to classify the patient based on the following:

1. The arterial BP measurements

2. The acuteness of the problem

3. The status of the patient in terms of antihypertensive therapy

4. The cause of hypertension in the patient: essential vs. secondary. In acute settings, BP elevation may be an appropriate response to stress such as hypoxia, hypercapnia, hypoxemia, or even intracranial hypertension (the Cushing response of hypertension and bradycardia).

PATIENT CARE

Clinical thinking.

• The definition of hypertension is an operational definition, which means that a BP is considered to be in the hypertensive range when it requires treatment to lower it, not just when it is above the number considered to be normal, and such treatment is required when the benefit of therapy outweighs the risk of therapy. This explains the changes in the definition of hypertension over the course of the years, motivated by treatment availability and data on treatment benefit and treatment targets.

• The seventh report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), published in 2003, has issued those definitions. 1 Based upon the average of two or more BP readings at each of two or more visits after an initial screen, the following classification is used:

• Normal blood pressure: systolic less than 120 mm Hg and diastolic less than 80 mm Hg

• Prehypertension: systolic 120 to 139 mm Hg or diastolic 80 to 89 mm Hg

• Hypertension:

Stage 1: systolic 140 to 159 mm Hg or diastolic 90 to 99 mm Hg

Stage 2: systolic ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic ≥100 mm Hg

• It is not the same thing to have hypertension and to have a BP that is not normal. The normal BP definition comes from studies recognizing a continuous rise in the risk of hypertension complications starting at a BP over 110/75 mm Hg (mainly cardiovascular morbidity and mortality).

• These definitions apply to adults on no antihypertensive medications and who are not acutely ill. If there is a disparity in category between the systolic and diastolic pressures, the higher value determines the severity of the hypertension. The systolic pressure is the greater predictor of risk in patients over the age of 50 to 60 years. Also, systolic blood pressure (SBP) is measured more reliably than diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and classifies most patients. Isolated systolic hypertension is common in elderly patients; younger hypertensive patients tend to have elevations of both SBP and DBP. An isolated elevation of the DBP is much less common.

• I need to know if the patient, especially in the acute setting, is presenting with malignant hypertension, hypertensive emergency, or hypertensive urgency.

• If the patient is already receiving antihypertensive therapy, the diagnosis of hypertension is made. I need to assess the particular therapeutic goal for the BP of this patient, since BP treatment goals vary from patient to patient (see JNC 7 report 1 ) and the appropriateness of the treatment.

• The decision to search for a secondary cause of hypertension and/or poor BP control is made on a case-by-case basis.

The history should search for precipitating or aggravating factors as well as an identifiable cause (secondary hypertension), establish the course of the disease, assess the extent of target organ damage, and look for other risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

• Duration and course of the disease

• Prior treatment, response, tolerance, and compliance. Noncompliance with treatment is an important cause of poor BP control.

• Medications, diet, and social history: Drugs that may aggravate or cause hypertension include sympathomimetics, steroids, NSAIDs, and estrogens; psychiatric medications causing a serotonin syndrome; cocaine and alcohol abuse. Withdrawal syndromes and rebound effects also need to be considered: alcohol, benzodiazepines, β-blockers, and clonidine.

• Family history

• Comorbidities, especially diabetes; diseases that can be secondary causes of hypertension (e.g., kidney disease); other cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., tobacco).

• Symptoms of sleep apnea: early-morning headaches, daytime somnolence, snoring, erratic sleep.

• Symptoms of severe hypertension, end-organ damage, or volume overload: epistaxis, headache, visual disturbances, neurologic deficits, dyspnea, chest pain, syncope, claudication.

• Symptoms suggestive of a secondary cause: headaches, sweating, tremor, tachycardia/palpitations, muscle weakness, and skin symptoms.

Physical Examination

• Proper measurement of BP: Away from stressors, with an appropriate cuff size, use Korotkoff phase V for auscultatory DBP. Korotkoff phase V is when the sounds disappear; one can use phase IV when they muffle if they do not disappear until a BP of 0 mm Hg. SBP, measured by auscultation, can and should also be measured through the radial pulse: when the cuff is inflated above the SBP, the radial pulse disappears. This maneuver allows the assessment of auscultatory gap (a stiff artery that does not oscillate and leads to an auscultatory underestimation of SBP) and pseudo-hypertension (a stiff artery not compressed by the cuff; SBP is overestimated). In selected settings, BP should be measured in both arms (especially in the younger patient to assess for coarctation of the aorta). Measurements should be repeated at different visits, unless BP is markedly elevated, before treatment.

• Vital signs , in particular heart rate in relationship to BP and treatments already taken. It may be important, especially in the acute setting, to know if the patient is febrile or hypoxic. Mental status is an important vital sign in the acute setting (hypertensive emergencies and urgencies).

• General appearance: body fat, skin (cutaneous manifestations of endocrinopathies causing secondary hypertension).

• Funduscopic examination to evaluate retinal complications.

• Thyroid examination.

• Cardiac auscultation (for murmurs and abnormal sounds: An S 4 gallop may indicate the stiff left ventricle of hypertensive heart disease).

• Vascular auscultation (carotid bruits, renal bruits, pulses): to assess atherosclerotic status and the presence of renal artery stenosis; the relationship between carotid artery disease, its treatment, and hypertension is not well understood.

• Abdominal examination , especially of the aorta and the kidneys.

• Neurologic examination , if applicable.

Tests for Consideration

IMAGING CONSIDERATIONS

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

Medicine A Competency-Based Companion With STUDENT CONSULT Onlin

WhatsApp us

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A case report of malignant hypertension in a young woman

Andrea michelli, stella bernardi, andrea grillo, emiliano panizon, matteo rovina, moreno bardelli, renzo carretta, bruno fabris.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2015 Oct 9; Accepted 2016 Jun 24; Collection date 2016.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Malignant hypertension is a condition characterized by severe hypertension and multi-organ ischemic complications. Albeit mortality and renal survival have improved with antihypertensive therapy, progression to end-stage renal disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. The underlying cause of malignant hypertension, which can be primary or secondary hypertension, is often difficult to identify and this can substantially affect the treatment outcomes, as we report here.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman presented with severe hypertension and acute renal failure. Initial evaluation demonstrated hyperreninemia with hyperaldosteronism and a possible renal artery stenosis at the contrast-enhanced CT scan. Although this data suggested the presence of a secondary form of hypertension, further exams excluded our first diagnosis of renal artery stenosis. Consequently, the patient did not undergo renal angiography (and the contrast media infusion associated with it), but she continued to be medically treated to achieve a tight blood pressure control. Our conservative approach was successful to induce renal function recovery over 2 years of follow-up.

This case highlights the difficulty in differentiating between primary and secondary forms of malignant hypertension, particularly when the patient presents with acute renal failure. Clinicians should consider renal artery ultrasound as a first level diagnostic technique, given that the presentation of primary malignant hypertension can often mimic a renal artery stenosis. Secondly, adequate control of blood pressure is essential for kidney function recovery, although this may require a long time.

Keywords: Malignant hypertension, Acute kidney injury, Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, Young woman

Malignant hypertension is a condition characterized by severe hypertension and multi-organ ischemic complications [ 1 ]. Incidence of malignant hypertension has remained stable over the years, although mortality and renal survival have improved with the introduction of antihypertensive therapy. However, progression to end-stage renal disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality [ 2 ]. The underlying cause of malignant hypertension can be primary or secondary hypertension, and identification of the latter is mandatory for choosing the correct treatment in order to control blood pressure and improve end-organ damage. However, correct diagnosis can be challenging [ 3 ]. This case highlights the difficulty in differentiating between primary and secondary hypertension, particularly when the patient presents with acute renal failure.

A 33-year-old woman was referred to our Internal Medicine Department by her GP after the recent diagnosis of severe hypertension. While the diagnosis of hypertension dated back to the day before, its onset was actually unknown, as the patient had no memory of having ever measured her blood pressure before, consistent with the low awareness that young adults have of their hypertension [ 4 ]. During the visit she complained of fatigue. Otherwise, her medical and family histories were unremarkable. She used to smoke no more than 5 cigarettes per day, did not take any prescription or over-the-counter medications and denied the use of recreational drugs, as confirmed by the negativity of the urine drug screening. On admission, her blood pressure was 240/140 mmHg, but her other vital signs were normal and physical examination was unremarkable. Initial laboratory studies identified the presence of renal failure (creatinine 2.11 mg/dL), hypokalemia (potassium 2.45 mEq/L), and anemia with thrombocytopenia (hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL, platelets 113.000/microm 3 ), which were likely to be hemolytic as LDH was elevated (572 U/L). There was also an elevated CRP level of 170 mg/L. As for end-organ damage, renal failure was associated with a proteinuria of 1.9 g over 24 h, while ultrasound revealed 2 normal-sized kidneys with echogenic parenchyma. The ECG showed signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, which was confirmed by echocardiography, as the interventricular septum thickness measured 19 mm and LV mass/BSA was 232 g/m 2 . The left ventricular ejection fraction was 50 %, and there was no aortic coarctation. Retinal examination revealed grade III hypertensive retinopathy, showing the presence of malignant hypertension, and antihypertensive drugs were promptly administered.

Given that the clinical characteristics suggestive of secondary causes of hypertension include early (i.e. < 30 years) and sudden onset of hypertension in patients without other risk factors, blood pressure levels higher than 180/110 mmHg, and presence of target end-organ damage [ 5 ], our next exams were aimed at excluding secondary causes of hypertension. These analyses showed that our patient had a hyperreninemia with a secondary hyperaldosteronism (renin 266.4 microUI/mL, aldosterone 38.1 ng/dL), which could be due to the presence of a renovascular disease, a renin-secreting tumor, or a scleroderma renal crisis [ 6 ]. This last hypothesis was however excluded by the absence of circulating autoantibodies, as well as the absence of other clinical and/or laboratory features suggestive of immunological disorders. Moreover, a week after the start of the antihypertensive therapy, not only CRP, but also hemoglobin, platelets, and LDH normalized, so that we ruled out also other conditions causing renal failure with thrombotic microangiopathy and secondary hypertension, such as the hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (PTT) [ 7 ].

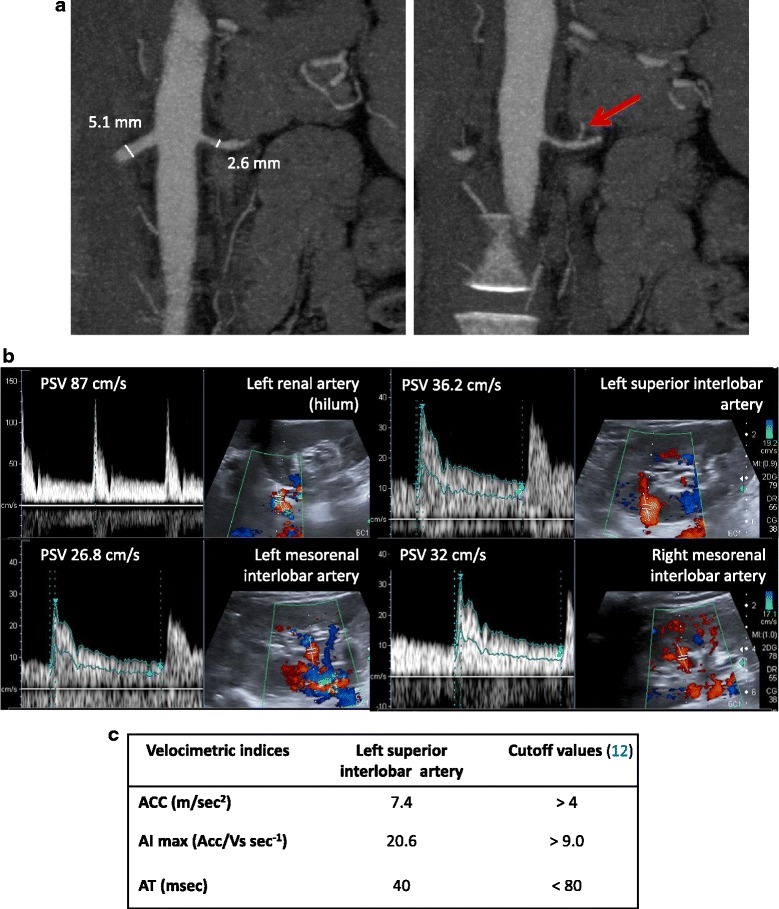

Given the severity of the case, the diagnosis of any underlying curable cause of the patient hypertension could not be overlooked. At that stage, taking into account the laboratory exams, we needed to rule out several possible causes of malignant hypertension, including renal artery stenosis, and other insidious diseases such as phaeocromocytomas [ 8 ], lymphomas, and other renin-secreting masses [ 9 ]. For this reason, according to current guidelines [ 10 , 11 ], the patient underwent a contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen. This exam did not show any suspicious masses. Nevertheless, it visualized a stenotic left renal artery (Fig. 1a ), suggesting that our patient could have a fibromuscular dysplasia causing renal artery stenosis. Despite most of our results were already strongly suggestive of renal artery stenosis, before prescribing any angiography with angioplasty, we requested a renal duplex ultrasound exam. The analysis of blood flow velocity, which was performed at the renal hilum as well as the intraparenchymal arteries, showed a normal hemodynamic pattern (Fig. 1b ). Moreover, both proximal and distal velocimetric indices were normal (Fig. 1c ). In particular, the maximal acceleration index, whose sensitivity is 93 % and specificity is 84 % [ 12 ], was greater than 9 s -1 , at all the sites. So, the renal duplex ultrasound did not confirm -to our surprise- the suspected renal artery stenosis.

a Abdomen CT scan image. The red arrow indicates the suspected left renal artery stenosis. b Renal echocolordoppler images and velocimetric indices. PSV, peak systolic velocity; ACC, maximal systolic acceleration, AI max , maximal acceleration index; AT, acceleration time

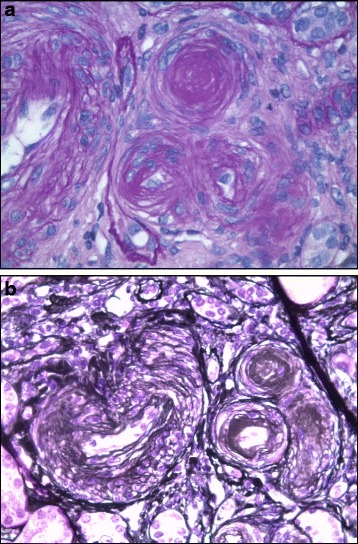

Given this result, the renal angiography was put on hold and the patient was treated with medical therapy only, achieving blood pressure normalization over a few weeks. Nevertheless, the persistence of the renal failure, despite blood pressure normalization, led us to perform a kidney biopsy in order to exclude primary renal diseases. Kidney biopsy showed relative sparing of glomeruli with predominant vascular damage (Fig. 2 ). This finding led us to the final diagnosis of malignant hypertension complicating an underlying primary (essential) hypertension with thrombotic microangiopathy.

a-b Representative images of kidney biopsy pathology, where vessel wall thickening with aspects of onionskin hyperplasia, endothelial layer detachment, and intraluminal platelet thrombosis with partial or complete obstruction of the vessel lumina can be seen

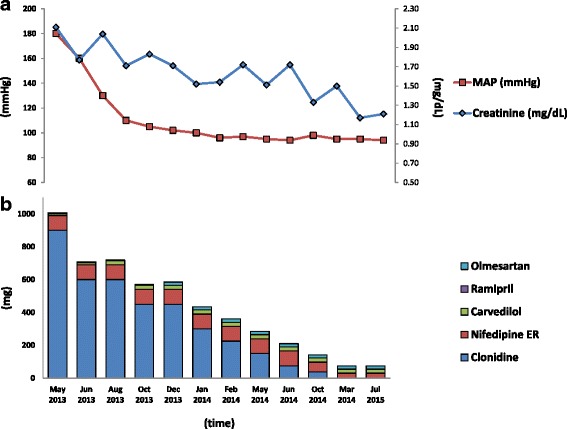

In this case antihypertensive therapy was able to successfully reduce blood pressure and induce end-organ damage recovery (Fig. 3 ). The echocardiography showed that after 1 year from the start of the therapy the interventricular septum thickness was of 11 mm, the LV mass/BSA was of 61 g/m 2 , and that the ejection fraction was of 74 %. The retinal examination did not show any cotton wool spots or flame hemorrhages. Proteinuria disappeared 4 months after hospitalization and renal function progressively ameliorated over the following 2 years (Fig. 3 ), reflecting a slow recovery process that is likely to include vascular remodeling [ 6 ].

Mean arterial pressure and creatinine normalization. a antihypertensive therapy reduction. b over the 2-year follow-up

Conclusions

This young woman’s presentation, marked by malignant hypertension with renal failure, was a diagnostic challenge. On one hand, the clinical presentation, the hyperreninemia with a secondary hyperaldosteronism were suggestive of a secondary form of hypertension, which at the contrast-enhanced CT scan seemed to be that of a renal artery stenosis. On the other hand, the renal duplex ultrasound exam was normal. Had there been a renal artery stenosis, the angiography (with angioplasty) might have been essential to successfully treat both hypertension and renal failure. On the contrary, if this had not been the case, unnecessary contrast media administration could have prevented renal recovery. In the end, we relied on the sensitivity [ 12 ] of the renal duplex ultrasound exam and decided to avoid the angiography.

This case highlights the difficulty in differentiating between primary and secondary hypertension in cases of malignant hypertension. More than half of the cases of malignant hypertension are in fact due to essential hypertension [ 13 ]. Moreover, be it essential or secondary, the clinical presentation of malignant hypertension can be the same. In addition, if the clinical presentation does not help discriminate, laboratory might not help either, in particular when it comes to the measurement of renin and aldosterone. Malignant hypertension is in fact typically associated with an activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [ 14 ]. Although the exact mechanism of malignant hypertension is unknown, several studies have implicated the RAAS as a key factor to its pathogenesis. The severe elevation of blood pressure would in fact lead to RAAS activation through microvascular damage and renovascular ischemia, and the increased production of Angiotensin II would in turn further increase blood pressure, leading to malignant hypertension [ 14 ]. In this setting, it is not unusual to find also other changes due to endothelial dysfunction [ 15 ], which might explain the transient microangiopathic hemolysis and increased CRP of our case.

Secondly, this case underlines the importance of performing the renal artery duplex ultrasound as the first-line (screening) exam when a renal artery stenosis is suspected, before considering the renal angiography with angioplasty, which is the reference standard for the anatomic diagnosis and treatment of renal artery stenosis [ 10 ]. Given that angiography is an invasive procedure that carries a risk for serious complications, less invasive techniques are advocated for the initial work-up of patients with suspected renal artery stenosis [ 12 ]. For this reason, the European consensus on the diagnosis and management of fibromuscular dysplasia suggests starting the patient evaluation with renal duplex ultrasound and then confirming the diagnosis with a CT-angiography prior to angioplasty. As compared to computed tomography, whose sensitivity has not always been found sufficient to rule out a renovascular disease [ 16 ], the renal duplex ultrasound exam, by the assessment of intrarenal velocimetric indices, has a high sensitivity and a high negative predictive value [ 12 ]. On the other hand, the results of the renal duplex ultrasound exam can be suboptimal if it is performed on obese patients, when apnea is difficult or impossible, and where local expertise is poor [ 10 ]. Nevertheless, in our case, given the patient’s slender figure and compliance, as well as local expertise, we took a step backward and decided to schedule a renal duplex ultrasound before the angiography. Contrary to the CT scan, the renal duplex ultrasound turned out to be negative. Therefore, given that there had not been technical biases hindering the diagnostic accuracy of the exam, we based our next decision on the high sensitivity and negative predictive value of the duplex ultrasound. This helped avoid the angiography as well as the additional contrast media administration that could have affected negatively the renal recovery [ 17 ].

Despite the fact that over the last 40 years the incidence of malignant hypertension has not changed and remains 2-3/100,000/year, its prognosis has improved significantly [ 13 ], which can be ascribed to the introduction of modern antihypertensive drugs and a better blood pressure control. Likewise, also renal prognosis has improved, and the probability of renal survival is 84 % and 72 % after 5 and 10 years of follow-up, respectively [ 18 ]. In the end, our case confirms that a tight control of blood pressure during follow-up is one of the main predictors of renal outcome in patients with malignant hypertension [ 18 ].

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and supporting materials.

All information supporting the conclusions of this case report has been included in the article.

Authors’ contributions

AM conceived and participated in the design the study, participated in the acquisition, drafted the manuscript. SB conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and revised the manuscript. AG EP MR participated in the acquisition of data, MB RC participated in the study design and in the revision of the manuscript. BF conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Contributor Information

Andrea Michelli, Email: [email protected].

Stella Bernardi, Phone: +0039 (0)403994324, Email: [email protected], Email: [email protected].

Andrea Grillo, Email: [email protected].

Emiliano Panizon, Email: [email protected].

Matteo Rovina, Email: [email protected].

Moreno Bardelli, Email: [email protected].

Renzo Carretta, Email: [email protected].

Bruno Fabris, Email: [email protected].

- 1. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Redon J, Dominiczak A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson PM, Burnier M, Viigimaa M, Ambrosioni E, Caufield M, Coca A, Olsen MH, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Clement DL, Coca A, Gillebert TC, Tendera M, Rosei EA, Ambrosioni E, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Hitij JB, Caulfield M, De Buyzere M, De Geest S, Derumeaux GA, Erdine S, Farsang C, Funck-Brentano C, Gerc V, Germano G, Gielen S, Haller H, Hoes AW, Jordan J, Kahan T, Komajda M, Lovic D, Mahrholdt H, Olsen MH, Ostergren J, Parati G, Perk J, Polonia J, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Ryden L, Sirenko Y, Stanton A, Struijker-Boudier H, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Vlachopoulos C, Volpe M, Wood DA. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Amraoui F, Bos S, Vogt L, van den Born BJ. Long-term renal outcome in patients with malignant hypertension: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-71. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Kitiyakara C, Guzman NJ. Malignant hypertension and hypertensive emergencies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:133–142. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V91133. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. NCHS Data Brief, No 133. 2013. p. 1–8. [ PubMed ]

- 5. Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Messerli FH. Secondary arterial hypertension: when, who, and how to screen? Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1245–1254. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht534. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Penn H, Howie AJ, Kingdon EJ, Bunn CC, Stratton RJ, Black CM, Burns A, Denton CP. Scleroderma renal crisis: patient characteristics and long-term outcomes. QJM. 2007;100:485–494. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm052. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Cheng XS, Adusumalli S, Singh H, DePasse JW, Smith RN, Haupert GT., Jr The root of this evil: microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and renal failure. Am J Med. 2015;128:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.08.021. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Iimura O, Shimamoto K, Hotta D, Nakata T, Mito T, Kumamoto Y, Dempo K, Ogihara T, Naruse K. A case of adrenal tumor producing renin, aldosterone, and sex steroid hormones. Hypertension. 1986;8:951–956. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.8.10.951. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Wong L, Hsu TH, Perlroth MG, Hofmann LV, Haynes CM, Katznelson L. Reninoma: case report and literature review. J Hypertens. 2008;26:368–373. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f283f3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Persu A, Giavarini A, Touze E, Januszewicz A, Sapoval M, Azizi M, Barral X, Jeunemaitre X, Morganti A, Plouin PF, de Leeuw P, Hypertension ESHWG, the K European consensus on the diagnosis and management of fibromuscular dysplasia. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1367–1378. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000213. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Grebe SK, Murad MH, Naruse M, Pacak K, Young WF, Jr, Endocrine S. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915–1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Bardelli M, Veglio F, Arosio E, Cataliotti A, Valvo E, Morganti A, Italian Group for the Study of Renovascular H New intrarenal echo-Doppler velocimetric indices for the diagnosis of renal artery stenosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:580–587. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000112. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Lane DA, Lip GY, Beevers DG. Improving survival of malignant hypertension patients over 40 years. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1199–1204. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.153. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. van den Born BJ, Koopmans RP, van Montfrans GA. The renin-angiotensin system in malignant hypertension revisited: plasma renin activity, microangiopathic hemolysis, and renal failure in malignant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:900–906. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.02.018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. van den Born BJ, Lowenberg EC, van der Hoeven NV, de Laat B, Meijers JC, Levi M, van Montfrans GA. Endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, thrombogenesis and fibrinolysis in patients with hypertensive crisis. J Hypertens. 2011;29:922–927. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328345023d. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Vasbinder GB, Nelemans PJ, Kessels AG, Kroon AA, Maki JH, Leiner T, Beek FJ, Korst MB, Flobbe K, de Haan MW, van Zwam WH, Postma CT, Hunink MG, de Leeuw PW, van Engelshoven JM, Renal Artery Diagnostic Imaging Study in Hypertension Study G Accuracy of computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography for diagnosing renal artery stenosis. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:674–682. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-9-200411020-00007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Shavit L, Reinus C, Slotki I. Severe renal failure and microangiopathic hemolysis induced by malignant hypertension--case series and review of literature. Clin Nephrol. 2010;73:147–152. doi: 10.5414/CNP73147. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Gonzalez R, Morales E, Segura J, Ruilope LM, Praga M. Long-term renal survival in malignant hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3266–3272. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq143. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.9 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Case report: A challenging case of severe Cushing's syndrome in the course of metastatic thymic neuroendocrine carcinoma with a synchronous adrenal tumor, Frontiers in Endocrinology, 15, (2024 ...

A 42-year-old black American woman with a 7-year history of hypertension and a family history of CVD is presented. The case illustrates the challenges and strategies of treating hypertension in this population, including the use of ARB and diuretics.

In this case study 60 years old women with Hypertension was identified in community remote area and checked the Health status of the client and monitored for one week and Health Education was ...

A 40-year-old black male with diabetes and hypertension presents with headache, fatigue, and muscle ache. His vital signs are elevated and he has a positive family history of hypertension.

A 17-year-old male with uncontrolled hypertension was diagnosed with coarctation of the aorta (CoA) by computed tomography angiography (CTA). The case report highlights the importance of screening for CoA in adolescents with typical signs and symptoms of secondary hypertension.

HTN - Case Study MK is a 51-year-old Caucasian male who is 6 feet tall and weighs 275 pounds (BMI 37.3) with an abnormal distribution of weight around his abdomen. He does not regularly exercise, does not like to cook, and eats fast food three to five times during the week. He has smoked one pack per day since the age of 20 (31 pack years).

Learn how to diagnose and manage hypertension in adults with five realistic case scenarios based on NICE guidance. Each case includes questions, answers, recommendations and references to the guideline.

Hypertension (Case 7) Elie R. Chemaly MD, MSc and Michael Kim MD. Case: A 59-year-old African-American woman is referred by her primary physician. She has had a history of severe hypertension for 38 years. She complains of dizziness, occipital headaches with blurred vision, and palpitations correlated with high BP sometimes reaching 200 mm Hg systolic and 120 mm Hg diastolic.

Case presentation. A 33-year-old woman presented with severe hypertension and acute renal failure. ... Postma CT, Hunink MG, de Leeuw PW, van Engelshoven JM, Renal Artery Diagnostic Imaging Study in Hypertension Study G Accuracy of computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography for diagnosing renal artery stenosis. Ann ...

Treatment: Case Study 2 Stage 2 hypertension in the setting of reported kidney disease Pt has 2 risk factors (CVD and family history) this might cause you to be a little more aggressive when initiating therapy Pt had an expected bump in creatnine with initiation of ACE inhibitor. Up to a 30% increase is acceptable.