An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

International trade and unemployment: towards an investigation of the Swiss case

Lukas mohler, simone wyss.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Contributed equally.

Received 2017 May 15; Accepted 2017 Dec 10; Issue date 2018.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

The topic of this paper has been motivated by the rising unemployment rate of low-skilled relative to high-skilled labour in Switzerland. Between 1991 and 2014, Switzerland experienced the highest relative increase in the low-skilled unemployment rate among all OECD countries. A natural culprit for this development is “globalization” as indicated by some mass layoffs in Switzerland and as commonly voiced in public debates all over the world. Our analysis, which is based on panel data covering the years 1991 to 2008 and approximately 33,000 individuals employed in the Swiss manufacturing sector, does not, however, confirm this presumption. We do not find strong evidence for a positive relationship between import competition and (low-skilled) individuals’ likelihood of becoming unemployed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s41937-017-0006-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: International trade, Unemployment, Low-skilled labour, Switzerland

Introduction

The relationship between international trade and employment has always been controversial. Trade economists have traditionally emphasized the efficiency-enhancing effects of international trade with no impact on total employment, at least in the medium and long term. Politicians and members of governments, in contrast, typically believe in an employment-increasing effect of international trade and often point to the numbers of jobs created by rising exports. 1 In the eyes of the public, however, international trade entails the danger of job destruction, particularly through increased imports. Trade economists agree that international trade may have distributional effects within countries. But they typically identify these effects in terms of changing factor prices: Low-skilled labour may, for example, lose ground—relatively and absolutely—in a high-income country as a result of international trade with (low-skilled) labour-abundant countries such as China or India.

In this paper, we investigate whether international trade is indeed linked to the likelihood of becoming unemployed. The focus on unemployment is motivated by our observation that the Swiss unemployment rate between low-skilled labour and high-skilled labour increased faster than that of any other OECD country between 1991 and 2014, with virtually no change in the relative wage rate between the same two groups of people. We use a representative panel data set for employees in the Swiss manufacturing sector, covering the period from 1991 to 2008, and link it to international trade data. We control for a number of individual characteristics, particularly regarding skills, age and experience, as well as industry properties. The analysis indicates that, for the Swiss economy, rising or high levels of imports do not seem to be a driving force behind the probability of becoming unemployed. Individual characteristics such as a short length of tenure, part-time employment, and low skills are, however, confirmed to be important factors that positively affect the individual’s risk of becoming unemployed.

Thus, the paper adds to the rapidly expanding literature on whether international trade is an important cause of the increase in the wage and unemployment gaps between skilled and unskilled labour that have been observed in the USA and some other countries since the 1980s. 2 We know since Stolper and Samuelson ( 1941 ) and, more generally, since Jones ( 1965 ) that trade liberalization tends to have a strong negative impact on some real factor prices and, if these are inflexible or search costs are involved, also on factor market clearing, as shown by Davis ( 1998b ), Davidson et al. ( 1999 ), and Egger and Kreickemeier ( 2008 ). Moreover, Feenstra and Hanson ( 2003 ) argue that the effects from trade in intermediate inputs may be similar to those caused by skill-biased technological change which is often made responsible for the wage gap in the US economy. Autor et al. ( 2013 ) found significant negative labour-market effects on the US economy of international trade between the USA and China and conclude: “Rising imports cause higher unemployment, lower labor force participation, and reduced wages in local labor markets that house import-competing manufacturing industries” (p. 2121).

Recent trade models, which introduce some labour market frictions, as used by Brecher and Chen ( 2010 ), Davis and Harrigan ( 2011 ), Helpman and Itskhoki ( 2010 ), Helpman et al. ( 2010 ), Larch and Lechthaler ( 2011 ), Mitra and Ranjan ( 2010 ), or Ranjan ( 2012 ), imply that relative unemployment between different types of labour may be affected by trade liberalization in a variety of ways. Moreover, these models come to the conclusion that international trade may also affect the overall unemployment level in an economy—positively or negatively. 3 In empirical analyses, a negative effect of trade on overall unemployment is found by Felbermayr et al. ( 2011 ) and by Gozgor ( 2014 ) in cross-country analyses, by Hasan et al. ( 2012 ) for India and by Francis and Zheng ( 2011 ) for NAFTA. 4 Chusseau et al. ( 2010 )—in a cross-country analysis—and Horgos ( 2012 )—for Germany—show that in the case of inflexible factor prices an increase in the relative unemployment rate between skilled and unskilled labour can to some extent be linked to trade—which the former call an “inequality-unemployment trade-off”. Fugazza et al. ( 2014 ) find a positive relationship between trade and unemployment in a panel of 97 countries if countries have “a comparative advantage in sectors that have high labour market frictions” (p. 1).

Compared to the existing literature, our empirical investigation is of particular interest for three reasons. First, it focuses on a small country whose international trade reflects a large share of its domestic output. The Krugman ( 2000 ) critique that a country’s trade volume is typically too small to explain effects on different types of labour hardly applies in this case (or at least to a much lesser extent). Second, our paper’s emphasis is on the unemployment rate, and not on wages as underlined by the majority of empirical research studies. 5 This focus is in line with the recent shift in research interest among trade theorists and labour-market economists as well as with the stylized facts applying to the Swiss economy. Finally, we add to the limited literature on Switzerland in this field. The relationship between international trade and unemployment has, to our knowledge, not been analysed to date for the Swiss case. 6

The remainder of the paper is as follows. The “ Background ” section presents stylized facts that explain our research strategy. The “ Methods ” section briefly describes our research methodology. The “ Results and discussion ” section presents the main results of the econometric analysis. The “ Conclusion s” section concludes.

Past research has been motivated by an inquiry into the impact of international trade on relative wages . Feenstra ( 2010 , pp. 10), for example, describes and discusses the development of the wages of “nonproduction” relative to “production” workers in US manufacturing from 1958 to 2006. If we interpret this ratio as the relative wage rate of high-skilled to low-skilled labour, the data clearly shows that the relative wages of unskilled labour fell considerably and constantly from 1986 to 2000. This observation has been the basis for the expanding literature on trade and the wage gap in the USA that also sparked our research interest with its focus on Switzerland.

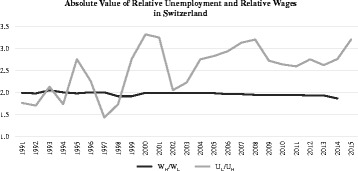

Such a development is, however, not observable for Switzerland. Using Swiss labour market panel data (Swiss Labor Force Statistic, SLFS) and the UNESCO skill classification scheme (International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED-97), 7 we calculated both the median gross wage rate of high-skilled ( W H ) and low-skilled ( W L ) labour, and the unemployment rate for the same two groups, i.e. U H and U L , for the period 1991 to 2014. Figure 1 shows that, over this period, the U L / U H rose with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2%, whilst the W H / W L remained roughly constant with a CAGR of − 0.3%. Thus, Fig. 1 serves as a motivation to study a possible relationship between international trade and (changes in) the relative unemployment of low-skilled and high-skilled labour in the Swiss case.

Evolution of relative wages and relative unemployment in Switzerland. Source: Own calculations based on FOS ( 2008 ), Wyss ( 2010 ) FOS ( 2016a , b )

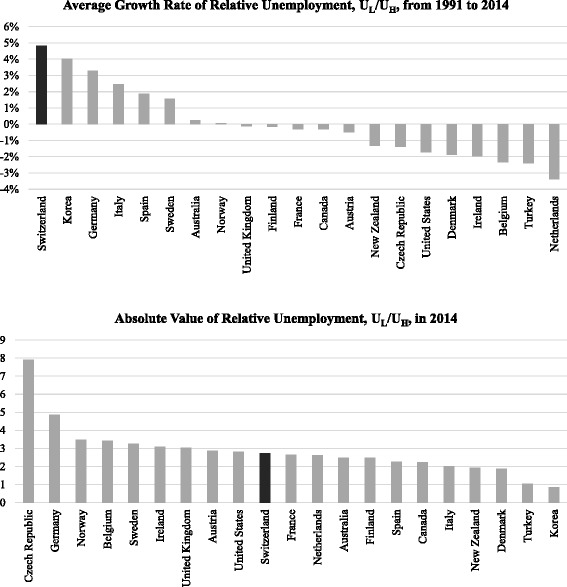

A comparison among 21 OECD countries implies that there is no other country in which U L / U H has grown as fast as in Switzerland from 1991 to 2014. 8 Figure 2 shows a CAGR of 4.8% of this ratio from 1991 to 2014 (top panel). It reveals that other countries such as South Korea or Germany also experienced a large rise in this ratio, whereas countries like the Netherlands or Belgium but also the USA or Canada demonstrate a decrease of the relative unemployment of low-skilled labour. Absolute numbers in the OECD data indicate that the Swiss U L increased from 1.2% (1991) to 8.8% (2014), whereas U H increased to a much smaller extent over this period (from 1.3 to 3.2%). Note, however, that the absolute value of the relative unemployment rate in Switzerland (2.7) is not extremely high, but rather puts the country in the middle of the reported OECD countries as shown in Fig. 2 (bottom panel). Given the strong and yet unbroken trend in the Swiss relative unemployment rate, it is of highest interest to assess whether trade may be a driving force of this development. 9

Average growth rate of relative unemployment (top panel, 1991–2014) and absolute value of relative unemployment (bottom panel, 2014) in OECD countries. Note: These are OECD countries for which data were available for the years considered. For the comparison in the top-panel, compounded average growth rates were taken. Source: Own calculations based on OECD (2007) and OECD (2015), Tables A8.4a and A5.4a, respectively

Trade theory stresses the importance of international trade in improving an economy’s allocation of resources, and not the creation of additional jobs. In a standard trade model, there is no expected link between trade liberalization and the total number of jobs in an economy. 10 The argument trade economists traditionally have put forward is that whilst more trade leads to some jobs being destroyed in the import-competing sector of an economy, new jobs are simultaneously being generated in the export sector.

An increase in unemployment is, however, compatible with the traditional trade theory if we, for example, extend a Heckscher-Ohlin type model to allow for some factor price inflexibility as shown by Davis ( 1998b ) or, adding trade in intermediate inputs, by Egger and Kreickemeier ( 2008 ). The reason is that trade typically leads to a decrease in the relative demand for low-skilled labour in a (human) capital-rich country. If the induced fall of the price of low-skilled labour—predicted by the Stolper Samuelson Theorem—is prevented by labour market rigidities, unemployment for low-skilled labour tends to rise with trade liberalization.

Recent trade models expanded in this direction allowing for a number of labour market frictions and/or using intra-industry trade models based on heterogeneous firms and job-specific rents. It turns out that, in these set-ups, trade liberalization may indeed raise unemployment of particular types of labour and affect overall unemployment in an economy. In Brecher and Chen ( 2010 ), for example, the unemployment rates of low- and high-skilled labour “often move in opposite directions” (p. 990), whereas the change of aggregate unemployment is ambiguous. Davis and Harrigan ( 2011 ) argue that, in their model, trade liberalization may destroy a considerable share of highly paid jobs without, however, necessarily affecting overall unemployment. Helpman and Itskhoki ( 2010 , p. 1100) find the surprising result that “[T]he opening to trade raises a country’s rate of unemployment if its relative labour market frictions in the differentiated sector are low.” And Hasan et al. ( 2012 , p. 269) come, based on their empirical study of India, to the conclusion: “Moreover, our industry-level analysis indicates that workers in industries experiencing greater reductions in trade protection were less likely to become unemployed, especially in net exporting industries.” 11

The focus of our paper is empirical. We seek to explain the employment status of individuals over time, i.e. whether they become unemployed or not, by changes and levels of imports and exports, controlling for various individual characteristics and industry factors. The explained variable (i.e. the individual’s status, y i ) is qualitative in nature and takes a value of 1 if an individual becomes unemployed in a certain year and 0 otherwise. The explanatory variables will be qualitative or quantitative as will be made more precise in the “ Results and discussion ” section. The econometric analysis of the relationship between the two is largely based on the linear probability model (OLS) that includes year and industry fixed effects and, for some specifications, individual fixed effects. We use this model as coefficients will be easier to interpret, but we also report the results of the analysis based on the logit model. They turn out to be qualitatively the same.

Results and discussion

We base our analysis on representative industry-panel data for the years 1991 to 2008. During this period, Switzerland established a number of bilateral agreements with trading partners—including the European Union (EU). Moreover, mutual trade liberalization between Switzerland and other countries also occurred through new membership of countries to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the EU and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). 12 All of this implies pressure and adjustments that are typical for trade liberalizations. The question we now seek to answer is whether international trade indeed had a significant impact on the probability of (particularly low-skilled) individuals to become unemployed. If this is the case, international trade could be one reason for the increase of the relative unemployment rate for low-skilled labour described in the “ Background ” section.

Using micro data on individuals’ characteristics, we intend to assess whether an individual, who becomes unemployed, does so because of his or her particular exposure to international trade, controlling—amongst others—for skills. We present detailed summary statistics of the underlying data in the “ The data ” section and then run regressions of the change in the individual employment status on individuals’ characteristics and the trade variables in the “ Changes in employment status, individual characteristics and trade ” section. The “ Refinement of the trade variables and inclusion of individual fixed effects ” section uses a number of refined trade variables and includes individual fixed effects. The “ Sensitivity analyses ” section concludes with some sensitivity analyses.

For the industry panel data, we rely on the Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS). It is based on an annual and representative collection of information from Swiss residents (including foreigners, but excluding cross-border commuters) by the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics (FOS). The SLFS is in line with the methods used by the International Labour Office (ILO) which defines those individuals as unemployed who are not working, but searching for a job and ready to assume employment quickly.

This data source includes a pool of roughly 33,000 individuals over a period of 18 years (1991–2008) who were employed in the secondary sector (manufacturing) in Switzerland. As we want to attribute an industry to an individual, characterizing in which kind of industry the worker is employed, we link the SLFS data (FOS, 2009a ) on the industry two-digit SIC level with the Swiss Foreign Trade Statistics (EZV, 2009 ) and the National Account Statistics of the FOS ( 2009b ). To also characterize whether an individual works in a so-called ICT industry (i.e. an industry which displays an above-average intensity in the use of information and communication technology) or in a GAV industry (i.e. an industry which shows an above-average coverage of collectively bargained labour contracts), we also take into account the ICT-Survey of the KOF Swiss Economic Institute (KOF, 2005 ) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) and the GAV-Statistics of the FOS ( 2002 ).

Summary statistics of the data used in our regressions are provided in Table 1 . The first column entitled “Change in Employment Status” is composed of individuals who are either employed during the full period of observation or indicate a change in their employment status from employment to unemployment. The second column “Employment Status” includes all individuals with a status of employed or unemployed. This leads to a maximum of 20,928 (40,875) observations of which 463 (1226) show a change in the employment status from employed to unemployed (show a status of unemployment). These observations stem from 10,242 (18,995) individuals, of which 461 (1008) show a change in their status from employed to unemployed (show at least once a status of unemployment). 13

Summary statistics of the regression data set

Source: Panel data set constructed using data from FOS ( 2009a ), EZV ( 2009 ), KOF ( 2005 ) and FOS ( 2009b ). Note that trade covariates and industry characteristics describe the industry which an individual is employed in

Our main econometric analyses will concentrate on the observations reported in the first column of Table 1 . However, we will take into account the observations in the second column in our sensitivity analysis (“ Sensitivity analyses ”). Regarding the first column, the mean year-to-year change in percentage of import (export) values in the 17 manufacturing industries considered in the analysis amounts to 6.9% (7.6%). 40.1% of the observations are linked with “GAV industries”, whereas 37.2% of the observations include individuals employed in “ICT industries”. 14 The distribution of the observed worker characteristics are reported in the bottom part of Table 1 and speak for themselves.

Changes in employment status, individual characteristics and trade

We first regress changes in the individual employment status on the individuals’ characteristics and aggregate trade variables, using the following linear probability model with time and industry fixed effects:

Note that i indexes the individual and t the year. The left-hand variable, y it , takes the value of 1 if the individual i becomes unemployed in t and was employed in t − 1, and it takes the value of 0 if the individual remains employed in t . The probability of becoming unemployed over time is explained based on a number of right-hand independent variables, starting with an individual being employed in an ICT and GAV industry, a number of socio-demographic factors (SDF) of individual i in t as well as imports ( IM ) and exports ( EX ) of the industry, in which the individual i is employed, in time t . Note that we use levels (i.e. the value) as well as changes (i.e. in percentage) for the trade covariates and also include lags. We also interact some of the variables with the individuals’ skill level (L, M, H). The results are provided in Table 2 .

Linear regressions of changes in employment status on trade variables and individual characteristics

Note: All regressions including year and industry fixed effects

Source: Panel data set constructed using data from FOS ( 2009a ), EZV ( 2009 ), KOF ( 2005 ) and FOS ( 2009b )

*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

We start with a base regression, leaving out all trade variables. The results are reported in the first column of Table 2 . They show that the likelihood of becoming unemployed significantly depends on the individual’s qualifications (medium and low skills) and type of contract (part-time, temporary contract). 15 In this respect, we find also a positive relationship between the individuals’ likelihood of becoming unemployed and a short or medium tenure and for foreigners (typically due to a lack of local language skills). Married and widowed employees, on the other hand, are associated with a lower probability of becoming unemployed. Note that the coefficient for employment in an ICT-intensive industry or in a GAV industry is not significantly different from zero. The size of the coefficients in Table 2 can be interpreted as follows: Compared to a high-skilled worker, a low-skilled employee bears a 1.3% higher probability of becoming unemployed.

Columns (2) to (5) include levels and changes in the trade variables ( IM , EX ), also interacted with individuals’ skill levels (low-skilled, medium-skilled). Trade levels enter the estimation in logs, whereas “trade first differences” are calculated as the rate of year-to-year changes in percentage. We also add lagged trade variables (lagged by 1 year) to allow for a more deferred adjustment process. Note that, overall, the coefficients of worker and job characteristics do not change in a qualitative manner in these different specifications, nor do the GAV and ICT coefficients (except for the low skill level as a consequence of its interaction with the trade variables). We find some evidence (on the 5% significance level) for a significant effect of import levels on the probability of becoming unemployed for low-skilled employees: A 1% higher import value is associated with a 0.017% (0.016% for lagged imports) higher probability of becoming unemployed. In other words, low-skilled individuals who work in industries characterized by relatively large contemporaneous imports may, ceteris paribus, face a slightly greater likelihood of becoming unemployed. As shown in the fourth and fifth columns of Table 2 , no significant effects are found for first differences (i.e. changes ) in import and export values: A change in imports or exports in a certain industry does not significantly affect the probability of becoming unemployed.

We further investigate the impact of trade in the next subsection by using more refined trade variables and by including individual fixed effects to take into account any unobserved individual characteristics.

Refinement of the trade variables and inclusion of individual fixed effects

We now regress changes in the individual employment status on a number of trade variables, distinguishing between imports in finished and intermediate products and between trade with the North and the South. 16 We eliminate individuals’ characteristics as well as the GAV and ICT variables as we now use individual fixed effects. 17 We continue applying the linear probability model with time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered by industry. We start with taking trade levels (in logs) as explanatory variables and then proceed to look at the rates of changes of the same variables. The results are reported in Tables 3 and 4 .

Linear regressions of changes in employment status on trade levels using individual fixed effects

Note: All regressions including time and individual fixed effects

Linear regressions of changes in employment status on trade differences using individual fixed effects

The estimates reported in Table 3 do not lend broad support for a positive relationship between the level of imports and the risk of becoming unemployed: Most coefficients of the import-level variables are not significantly different from zero. One exception at the 1% significance level is the coefficient of the 1-year lagged imports of final products from the South (fourth column): Individuals employed in an industry characterized by a 1% higher value of imports in this category encounter a 0.008% higher probability of becoming unemployed.

The results of the analogous estimations for first differences (i.e. rates of changes) in the import and export variables in a given industry are reported in Table 4 . We neither find an unambiguous relationship between changes in imports and the risk of unemployment nor is any of the relationship significant on the 1% level. However, we find that the coefficients for a lagged increase in final as well as intermediate imports from the South are significantly different from zero (on the 5% level, fourth column). Note that the economic impact of this effect is small: A 1% increase in import value, denoted as 0.01 in the dataset, leads to an increase in the probability of becoming unemployed by 0.004%. On this background, the fact that the coefficients of intermediate export products to the South in columns (2) and (4)—0.004 and 0.007—are significantly different from zero (and positive) should not be overvalued.

Sensitivity analyses

We finally try a number of different specifications to test the robustness of our results. Detailed results of these analyses are available from the Additional file 1 to this paper (Tables OA1 to OA5).

First, we replicate the results presented in Tables 2 , 3 and 4 using the logit regression model (Additional file 1 : Tables OA2 and OA3). Regarding the results in Table 2 , the logit estimates confirm a relationship between import levels and the likelihood of low-skilled workers of becoming unemployed: Coefficients are significantly different from zero (at the 5% level) with a positive sign. Also, we can confirm sign and significance level for the individual socio-demographic variables included and reported in Table 2 . Using a logit model with fixed effects, analogously to Tables 3 and 4 , we do not find any significant effects of the trade variables, regardless of whether we use levels or first differences as explanatory variables. 18 Hence, the logit estimations lead to qualitatively identical results as the linear regression model.

Second, we use the employment status (i.e. the information whether an individual is employed (0) or unemployed (1) in period t )—instead of the change of the employment status—as the dependent variable (summary statistics can be found in the second column of Table 1 ). As a start, we replicate the estimations described in Table 2 with the new dependent variable (see Additional file 1 : Table OA4). Again, we can confirm positive coefficients regarding import levels interacted with low-skilled labour for lagged imports (significantly different from zero at the 5% level). Furthermore, we use trade levels and first differences as explanatory variables in a model with individual fixed effects and find results that are qualitatively similar to those in Tables 3 and 4 . The results for the employment status as the dependent variable are reported in Additional file 1 : Table OA5. Most coefficients are not significantly different from zero. One exception is, again, the lagged level of final imports from the South with a coefficient of 0.016 (significantly different from zero at the 1% level). However, we also find a negative coefficient for the lagged first differences of intermediate imports from the North (− 0.010, significantly different from zero at the 5% level), leaving us with an ambiguous result regarding the effect of imports on the status of employment. 19

Third, and complementary to the analyses in Tables 3 and 4 (with again the change of the employment status as the dependent variable), we use second differences of the trade variables (e.g. [ IM t − ( IM t − 2 )/( IM t − 2 )]) instead of first differences and 2-year lags of trade levels instead of 1-year lags. All the results including the ones from Tables 3 and 4 are reported in Additional file 1 : Table OA1. We find a negative coefficient for the second differences without lags of intermediate imports from the North (− 0.006, significantly different from zero on the 5% level) in column 14. Furthermore, a positive coefficient is found for intermediate import levels from the North lagged by 2 years (0.013, significantly different from zero on the 5% level) in column 6. All the other import coefficients are insignificantly different from zero. 20 Thus, also in these regressions, we do not find unambiguous evidence for a positive relationship between imports and the probability of becoming unemployed.

Conclusions

This paper has been sparked by the omnipresent public concern in many industrial countries that international trade through specialization and outsourcing may cause income losses and unemployment, particularly for low-skilled labour. The striking increase in the Swiss unemployment rate of low-skilled relative to high-skilled labour from 1991 to 2014—with virtually no changes of relative wages—motivated us to focus our research on the relationship between international trade and unemployment for Switzerland.

Our assessment of the Swiss case does not confirm the public concerns. The econometric analysis of a data set of roughly 30,000 workers in the Swiss manufacturing sector from 1991 to 2008, which we link with the Swiss foreign trade statistics, does not, overall, support the presumption that an increase in imports has a statistically significant (and positive) effect on the probability of individuals of becoming unemployed, irrespective of their skills. Thus, we seem to be left with other well-established factors such as the level of skills, temporary employment or the length of tenure to explain the individuals’ risk of unemployment. The startling rise in the relative unemployment rate of low-skilled labour and, at the same time, the somewhat comforting constant relative wage rate of low-skilled labour in Switzerland from 1991 to 2014 still remains to be explained. Obvious candidates to look at more carefully would, in our view, be a skill-biased technological change for the relative unemployment rate and the compositional change in immigration for the relative wage rate. 21

Our investigation therefore only offers an initial basis for a more profound analysis of the labour market effects of trade or, more generally, of globalization for Switzerland. First, the fact that we find a weak (albeit small) positive relationship between low-skilled individuals working in industries characterized by a relatively high level of imports (particularly from the South) and the probability of their becoming unemployed may indicate something that we are not able to identify, given the limited statistical power of our data set which includes only a relatively small number of individuals who became unemployed. Second, we use exports as a control variable for (changes in) demand, because increasing imports have different effects on employment if they are combined with rising exports. This presents no problem as long as the domestic markets remain relatively small, which may, even in a small country such as Switzerland, not always be the case. If compatible data were available, a more sophisticated ratio could be used such as the import penetration ratio proposed by Autor et al. ( 2014 ) for the US industries.

Third, the fact that the individuals’ characteristics could only be linked to the two-digit SIC industry level, may even out a large amount of variation within industries: An individual’s employment status may be affected by imports on a sub-industry level, which might remain unobserved on the aggregated industry level. Also, and related to this, individuals employed in large multiproduct firms may be linked to an industry which is not really relevant to their actual occupation. Thus, an analysis based on more disaggregated, possibly even firm- or establishment-level, data may challenge our results.

On the other hand, this paper’s lack of findings in support of a strong positive relationship between import competition and the risk of unemployment could also be a consequence of the relatively low unemployment rate in Switzerland and the alleged high degree of flexibility in the Swiss labour market. If individuals lose their job because of import competition, but immediately find a new one, they never become unemployed. In this regard, it is interesting to note that our analysis of six announced mass-layoff cases in Swiss manufacturing due to globalization between 2001 and 2006 revealed exactly this situation: Only one quarter of the displaced workers were, in the end, dismissed by their companies and thus became, at least for a short term, unemployed (see Wyss, 2010 ). The others swiftly found a new job in the same or in another company or industry.

Additional file

Table OA1. Linear regressions of changes in employment status on trade variables using individual fixed effects. Table OA2. Logit regressions of changes in employment status on trade variables and individual characteristics, regression coefficients. Table OA3. Logit regressions of changes in employment status on trade variables using individual fixed effects, regression coefficients. Table OA4. Linear regressions of employment status on trade variables and individual characteristics, regression coefficients. Table OA5. Linear regressions of employment status on trade variables using individual fixed effects, regression coefficients. (DOCX 54 kb)

Acknowledgements

All persons who provided feedback as well as some minor support (data, editorial) to the different versions of the paper are mentioned in the acknowledgement.

We would like to thank the co-editor, Volker Grossmann, and two anonymous referees for their extremely helpful suggestions which led to a considerable improvement of the analysis in our paper. We also thank Marius Brülhart, David Green, Douglas A. Irwin, Ronald W. Jones, Peter Kugler, Christian Rutzer and George Sheldon for helpful feedback to earlier drafts as well as Dragan Filimonovic, Lukas Hohl and Hermione Miller-Moser for data and editorial support. We also benefited from discussions at the Annual Conference of the European Trade Study Group (ETSG), the Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics and a lunch seminar at the Department of Economics of the University of British Columbia (UBC). Simone Wyss gratefully acknowledges financial support from the WWZ-Forum and the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) during an early stage of the research project.

Industry dummies for ICT intensity and GAV intensity

Source: Own composition based on KOF ( 2005 ) and FOS ( 2002 ). The ICT dummy equals 1 if the investment in information and communication technology is above the average of 16% of total investment. The GAV dummy equals 1 if the coverage by collective labour contracts is above the average of 36%

Authors’ contributions

LM has implemented all the regressions in the second and the final version of the paper and given input to the first and second revisions of the paper. He also contributed to the letters to the editor and the referees. RW has written the first version of the paper and re-written the paper as part of the first and second revisions. He also wrote the letters to the editor and the referees. RW and LM have been closely working together in the first and second revisions of the paper. SM has collected the data and implemented the econometric analysis for the first version of the paper. She also answered questions regarding the data and the original regressions throughout the revision process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Interestingly, this point of view is emphasized, for example, in an early document of the U.S. Department of State ( 1945 ) that formed the basis of the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The title “Proposals of Expansion of World Trade and Employment” is revealing.

For early contributions see, for example, Berman et al. ( 1994 ), Borjas et al. ( 1991 ), Davis ( 1998a , 1998b ), Feenstra ( 1998 , 2010 ), Krugman ( 1995 , 2000 ), Lawrence and Slaughter ( 1993 ), Leamer ( 1998 , 2000 ) or Murphy and Welch ( 1991 ).

Whereas the overall effect on unemployment remains ambiguous or depends on parameters in these models, Dutt et al. ( 2009 ) predict a reduction in overall unemployment as a result of trade.

Moser et al. ( 2011 ) find a small (negative) effect from a reduction in the international competitiveness of firms on job flows for Germany, and more so on job creation rather than on job destruction.

See for example Feenstra and Hanson ( 1999 ), Hijzen et al. ( 2005 ) and OECD ( 2007 ) for a broad overview.

See Suarez ( 1998 ) and Müller, Marti and Nieuwkoop ( 2002 ) who focus on trade and wages. Other studies such as Sheldon ( 2007 ), Puhani ( 2003 ) and Arvanitis ( 2005 ) analyze shifts in supply and demand on the Swiss labour market, but do not explicitly investigate the effects of trade.

Note that, throughout this paper, high-skilled (H) is defined as people with tertiary education (ISCED 5-6: university, college of higher education (Fachhochschule) and school of higher education (Höhere Fachschule). Low-skilled (L) is defined as individuals with primary or lower secondary education (ISCED 1-2: mandatory education with no professional training qualification). Medium-skilled (M) is defined as individuals with upper secondary education (ISCED 3-4: professional education which, most importantly, includes completed apprenticeships).

Note that U L is defined as the unemployment rate of the 25–64-year-olds with “below upper secondary education”, whereas U H is defined as the unemployment rate of the 25–64-year-olds with “tertiary education”; see OECD ( 2007 , 2015 ).

Interestingly, South Korea shows the lowest absolute rate of relative unemployment in 2014 despite the considerable increase reported in Fig. 2 . On the other extreme, the Czech Republic shows a fall of the relative unemployment rate from 1991 to 2014, but remains the country with the highest ratio in 2014; note that, in 2014, U L ( U H ) equaled 20.7% (2.6%) for this country (see OECD ( 2015 , Table A5.4a)).

Baldwin ( 1994 , p. 73) once called the view that trade affects the number of jobs as “utter nonsense from the medium- or long-run economic perspectives”. Davidson et al. ( 1999 ) would, however, add that in a trade model with labour market frictions this is, in principle, possible, and mainly an empirical question (p. 273).

Dutt et al., 2009 , p. 33) emphasize a “fairly strong and robust empirical support (…) for the Ricardian prediction that trade openness and unemployment are negatively related across all countries”. The intuition is that trade raises productivity which increases the search effort of employees and employers that, in turn, reduces unemployment.

Note that, during this period, Switzerland or EFTA (to whom Switzerland belongs) established free trade agreements with approximately 20 countries (e.g. with Turkey (1992), Mexico (2001), South Korea (2006) and China (2014)), reached two bilateral agreements with the EU (1999, 2004) and was—through its free trade agreement (1972) and the two bilateral agreements with the EU—also affected by the enlargement of the EU by 13 new member countries in 2004, 2007 and 2013. Finally, there are approximately 30 countries (including China in 2001) that became additional members of the WTO, after its foundation in 1995 until 2008, and thus achieved improved mutual market access with Switzerland.

The deviation to all 33,000 individuals mentioned above is due to the fact that many individuals exhibit missing values in at least one of the variables of interest.

See Appendix : Table 5 regarding the assignment of individual industries. GAV stands for “Gesamt-Arbeits-Vertrag” and means collective bargaining contract; ICT stands for “Information and Communication Technology”.

Here and in the following we consider coefficients as significantly different from zero if they reach at least the 5% level.

Note that Feenstra and Hanson ( 2003 ) also base their analysis on annual changes broken down to final and intermediate imports. Anderton and Brenton ( 1999 ) differentiate between imports from industrial and low-wage countries. Based on the Swiss Trade Statistics, intermediates are defined as items in the category “raw materials”, “semi-finished products” and “intermediate goods”. An alternative definition based on input-output tables is currently not feasible as relevant statistics are not available. We also distinguish between imports from the North (industrial countries) and the South (developing countries).

Individuals remain in the same industry throughout the observed period. Hence, ICT and GAV variables are omitted when using individual fixed effects.

One may observe that the logit analysis implies a positive relationship (significantly different from zero at the 5% level) between low-skilled individuals working in GAV-industries (interacted variable) and their probability of becoming unemployed.

Also the relationship between the employment status and exports (level, change) remains ambiguous in the analysis.

Note that we also use 1-year leads of the trade variables as “placebo tests”. We refrain from showing those results in the Additional file 1 as we do not find any significant results.

For analyses of skill-biased technological change, see the seminal contributions by Berman et al. ( 1994 , 1998 ) and Krugman ( 2000 ) as well as, for an attempt to disentangle trade and technology effects, Autor et al. ( 2015 ).

- Anderton B, Brenton P. Outsourcing and low-skilled workers in the UK. Bulletin of Economic Research. 1999;51(4):267–285. doi: 10.1111/1467-8586.00085. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arvanitis S. (2005), “Information technology, workplace organization and the demand for employees of different education levels: Firm-level evidence for the Swiss economy”, in: Kriesi, Hanspeter et. al. (Eds.), Contemporary Switzerland: Revisiting the special case, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 135-162.

- Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH. The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. American Economic Review. 2013;103(6):2121–2168. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2121. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH. Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets. The Economic Journal. 2015;125(584):621–646. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12245. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH, Song J. Trade adjustment: Worker-level evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2014;129(4):1799–1860. doi: 10.1093/qje/qju026. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baldwin R. Towards an integrated Europe. London: CEPR; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berman E, Bound J, Griliches Z. Changes in the demand for skilled labor within U.S. manufacturing: Evidence from the annual survey of manufactures. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1994;104:367–398. doi: 10.2307/2118467. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berman E, Bound J, Machin S. Implications of skill-biased technological change: International evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1998;113(4):1245–1279. doi: 10.1162/003355398555892. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borjas GJ, Freeman RB, Katz LF. How much do immigration and trade affect labor market outcomes? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1991;1:1–90. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brecher RA, Chen Z. Unemployment of skilled and unskilled labor in an open economy: International trade, migration, and outsourcing. Review of International Economics. 2010;18(5):990–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9396.2010.00921.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chusseau, N., M. Dumont, J. Hellier and G. Rayp (2010), “Is there a country-specific trade-off between wage inequality and unemployment?”, EQUIPPE Working Paper .

- Davidson C, Martin L, Matusz S. Trade and search generated unemployment. Journal of International Economics. 1999;48:271–299. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00040-3. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis DR. Does European unemployment prop up American wages? National Labor Markets and global trade. American Economic Review. 1998;88(3):478–494. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis DR. Technology, unemployment, and relative wages in a global economy. European Economic Review. 1998;42(9):1613–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00113-X. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis DR, Harrigan J. Good jobs, bad jobs, and trade liberalization. Journal of International Economics. 2011;84:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.03.005. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dutt P, Mitra D, Ranjan P. International trade and unemployment: Theory and cross-national evidence. Journal of International Economics. 2009;78(1):32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.02.005. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Egger H, Kreickemeier U. International fragmentation: Boon or bane for domestic employment? European Economic Review. 2008;52:116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2007.01.006. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- EZV . Aussenhandel der Schweiz 1991-2008. Bern: EZV; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feenstra RC. Integration and disintegration in the global economy. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1998;12:31–50. doi: 10.1257/jep.12.4.31. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feenstra RC. Offshoring in the global economy. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feenstra RC, Hanson GH. The impact of outsourcing and high technology capital on wages: Estimates for the U.S. 1979-1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1999;114:907–940. doi: 10.1162/003355399556179. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feenstra RC, Hanson GH. Global production sharing and rising inequality: A survey of trade and wages. In: Kwan Choi E, Harrigan J, editors. Handbook of international trade. Oxford: Blackwell; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Felbermayr G, Prat J, Schmerer H-J. Trade and unemployment: What do the data say? European Economic Review. 2011;55:741–758. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2011.02.003. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- FOS . Mindestlöhne in der Schweiz, Analyse der Mindestlohn- und Arbeitszeitregelungen in den Gesamtarbeitsverträgen von 1999-2001. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- FOS . Schweizerische Arbeitskräfteerhebung 1991-2007. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- FOS . Schweizerische Arbeitskräfteerhebung 1991-2008. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- FOS . Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnung 1991-2008. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- FOS (2016a), Ausbildungsstufen der ständigen Wohnbevölkerung , Neuchâtel: BFS.

- FOS (2016b), Monatlicher Bruttolohn nach Ausbildung , Neuchâtel: BFS.

- Francis J, Zheng Y. Trade liberalization, unemployment and adjustment: Evidence from NAFTA using state level data. Applied Economics. 2011;43:1657–1671. doi: 10.1080/00036840903194212. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fugazza, M, C. Carrère, M. Olarreaga and F. Robert-Nicoud (2014), “Trade in Unemployment”, Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities. Research Study Series , Nr. 64, New York: UNCTAD

- Gozgor G. The impact of trade openness on the unemployment rate in G7 countries. Journal of International Trade & Economic Development. 2014;23(7):1018–1037. doi: 10.1080/09638199.2013.827233. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hasan R, Mitra D, Ranjan P, Ahsan RN. Trade liberalization and unemployment: Theory and evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics. 2012;97:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.04.002. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Helpman E, Itskhoki O. Labour market rigidities, trade and unemployment. Review of Economic Studies. 2010;77:1100–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2010.00600.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Helpman E, Itskhoki O, Redding S. Inequality and unemployment in a global economy. Econometrica. 2010;78(4):1239–1283. doi: 10.3982/ECTA8640. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hijzen A, Görg H, Hine RC. International outsourcing and the skill structure of labour demand in the United Kingdom. The Economic Journal. 2005;115:860–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2005.01022.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Horgos D. International outsourcing and wage rigidity: A formal approach and first empirical evidence. Global Economy Journal. 2012;12:2. doi: 10.1515/1524-5861.1844. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones RW. The structure of simple general equilibrium models. Journal of Political Economy. 1965;73:557–572. doi: 10.1086/259084. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- KOF . Einsatz von Informations- und Kommunikationstechnologie (IKT) Zürich: ETHZ; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krugman PR. Growing world trade: Causes and consequences. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1995;25(1):327–377. doi: 10.2307/2534577. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krugman PR. Technology, trade and factor prices. Journal of International Economics. 2000;50:51–71. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(99)00016-1. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larch M, Lechthaler W. Comparative advantage and skill-specific unemployment. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy. 2011;11:1. doi: 10.2202/1935-1682.2673. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lawrence RZ, Slaughter MJ. International trade and American wages in the 1980s: Giant sucking sound or small hiccup? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Microeconomics. 1993;2:161–226. doi: 10.2307/2534739. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leamer E. In search of Stolper-Samuelson linkages between international trade and lower wages. In: Collins S, editor. Imports, exports and the American worker. Washington D.C: Brookings Institution; 1998. pp. 141–202. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leamer E. What’s the use of factor contents? Journal of International Economics. 2000;50:17–50. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(99)00004-5. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mitra D, Ranjan P. Offshoring and unemployment: The role of search frictions labor mobility. Journal of International Economics. 2010;81:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2010.04.001. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moser C, Urban D, Weder di Mauro B. International competitiveness, job creation and job destruction—An establishment-level study of German job flows. Journal of International Economics. 2011;80:302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.09.006. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Müller, A., M. Marti und R. van Nieuwkoop (2002), Globalisierung und die Ursachen der Umverteilung in der Schweiz , Strukturberichterstattung, 12, Bern: seco.

- Murphy KM, Welch F. The role of international trade in wage differentials. In: Marvin H, editor. Workers and their wages: Changing patterns in the United States. Washington DC: AEI Press; 1991. [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD . Education at a glance 2007, OECD indicators. Paris: OECD; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD . Education at a glance 2015, OECD indicators. Paris: OECD; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Puhani PA. Relative demand shocks and relative wage rigidities during the rise and fall of Swiss unemployment. Kyklos. 2003;56(4):541–562. doi: 10.1046/j.0023-5962.2003.00237.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ranjan P. Trade liberalization, unemployment, and inequality with endogenous job destruction. International Review of Economics and Finance. 2012;23:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2011.10.003. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheldon, G. (2007), Migration, Integration und Wachstum: Die Performance und wirtschaftliche Auswirkung der Ausländer in der Schweiz, FAI-Studie , 04/07.

- Stolper S, Samuelson P. Protection and real wages. Review of Economic Studies. 1941;9:58–73. doi: 10.2307/2967638. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suarez J. The employment and wage effects of import competition in Switzerland. International Journal of Manpower. 1998;19(6):438–448. doi: 10.1108/01437729810233271. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U.S. Department of State (1945), Proposals for Expansion of World Trade and Employment , Publication 2411 (November).

- Wyss, S. (2010), Internationaler Handel, Löhne und Arbeitslosigkeit in der Schweiz. Eine empirische Analyse in drei Studien, Universität Basel: Dissertation.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (784.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Learning Materials

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Trade and Unemployment

Delve into the intricate dynamics of trade and unemployment in this comprehensive guide through the world of macroeconomics. Gain a fundamental understanding of how international trade interacts with the job market and informs unemployment rates. Discover the effects and consequences of trade frictions, and evaluate varying trade policies in light of their implications on employment. This resource brings substantial insight into the interconnected realms of trade, unemployment, and macroeconomics, dissecting their critical intersections within the broader economic landscape. Moreover, it introduces an engaging exploration of globalisation's role in these phenomena, punctuated by revealing historical case studies and comparative analyses.

Millions of flashcards designed to help you ace your studies

- Cell Biology

What effect does globalisation have on trade and unemployment?

How does high unemployment impact trade according to contemporary trade theories in macroeconomics?

What is the relationship between trade and unemployment in macroeconomics?

How do the effects of local trade and international trade on unemployment differ?

What are the positive effects of International Trade on Unemployment?

How do macroeconomic factors like exchange rates and business cycles affect trade and unemployment?

How does demand-pull inflation relate to trade and unemployment?

What is the influence of trade equilibrium on the job market?

What are trade frictions in macroeconomics?

What are the consequences of trade frictions in macroeconomics?

How can trade frictions lead to unemployment?

Achieve better grades quicker with Premium

Geld-zurück-Garantie, wenn du durch die Prüfung fällst

Review generated flashcards

to start learning or create your own AI flashcards

Start learning or create your own AI flashcards

Vaia Editorial Team

Team Trade and Unemployment Teachers

- 22 minutes reading time

- Checked by Vaia Editorial Team

- Aggregate Supply and Demand

- Economic Performance

- Economics of Money

- Financial Sector

- International Economics

- AA Schedule

- Advantages of Negotiation

- Anti Globalization Movement

- Appreciation and Depreciation

- BOP Current Account

- Balance of Trade

- Barriers to Trade

- Basics of International Economics

- Benefits of Tariffs

- Bimetallic Standard

- Bretton Woods System

- Capital Flight

- Central Bank Intervention

- Changes in Exchange Rate

- Collective Action

- Comparative Advantage

- Comparative Advantage vs Absolute Advantage

- Consumption Patterns

- Crisis in Venezuela

- Current Account Deficit

- Current Account Surplus

- Debt Default

- Determinants of Aggregate Demand

- Determinants of Consumption

- Devaluation and Revaluation

- Developed Countries

- Developing Countries

- Dynamic gains from Trade

- Economic Development

- Economic Globalisation

- Euro Crisis

- European Currency

- European Monetary System

- European Single Market

- Exchange Rate

- Exchange Rate Pass Through

- Exchange Rate and Net Exports

- Exploitation

- Export Led Growth

- Export Subsidies

- Export Subsidy

- External Balance

- External Economies

- External Economies of Scale

- Factor Price Equalization

- Factor Prices

- Factors Influencing Foreign Exchange Market

- Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

- Fiscal Expansion

- Fixed Exchange Rate

- Floating Exchange Rate

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Foreign Exchange Intervention

- Foreign Exchange Market

- Four Asian Tigers

- Free Trade Zone

- Funding Economic Development

- Global Economic Challenges

- Global Trade

- Gold Exchange Standard

- Heckscher-Ohlin Model

- Horizontal FDI

- Import Quotas

- Import Substitution Industrialization

- Imported Inflation

- Increase in Money Supply

- Infant Industry Argument

- Inflation and Real Exchange Rates

- Instruments of Trade Policy

- Integrated Market

- Internal Balance

- International Capital Flows

- International Companies

- International Labor Standards

- International Loans

- International Monetary Systems

- International Trade

- International Trade Agreements

- International Trade In Asia

- Intra-Industry Trade

- LL Schedule

- Labour Mobility

- Local Content Requirements

- Location of Production

- Low Wage Workers

- Managed Float

- Market Integration

- Market Size

- Monetary Approach to Exchange Rate

- Monetary Trilemma

- Nominal Exchange Rate

- Pattern of Trade

- Patterns of world trade

- Policy Formulation

- Pollution Haven

- Population Growth

- Preferential Trade Agreements

- Price Specie Flow Mechanism

- Production Possibilities

- Protectionism

- Purchasing Power Parity

- Real Exchange Rate

- Real Income

- Real Interest Parity

- Relative Wages

- Rent Seeking

- Ricardian Model

- Short Run Output

- Skill Biased Technological change

- Specialisation

- Specific Factors Model

- Standard Trade Model

- The Debt Crisis of the 1980s

- The Demand for Resources

- The Economic Basis for Trade

- The Equilibrium Exchange Rate

- The Gap between Rich and Poor

- Trade Agreements

- Trade Deficit and Surplus

- Trading Blocs

- Trans Pacific Partnership

- Transportation Cost

- Uruguay Round

- Vertical FDI

- Voluntary Export Restraints

- Welfare Effects

- World Trade Organisation

- Introduction to Macroeconomics

- Macroeconomic Issues

- Macroeconomic Policy

- Macroeconomics Examples

- National Income

Jump to a key chapter

Trade and Unemployment: An Overview in Macroeconomics

Trade and unemployment are two concepts deeply intertwined in the study of macroeconomics. They influence each other in many ways and forming a clear understanding of this relationship can provide valuable insights into the dynamics of economies worldwide.

Basic Understanding: Trade and Unemployment

Unemployment refers to the state of being without a job despite actively seeking work, while trade involves the exchange of goods and services, either within a country (domestic trade or internal trade) or between different countries (international trade). A close look at these definitions reveal the underlying linkage between these two concepts. Increased trade could lead to job opportunities, thereby reducing unemployment. However, this is not always the case, as the effect of trade on employment could be positive or negative depending on various factors.

Demand-pull inflation is a macroeconomic concept that describes a situation where the demand for goods and services in an economy outpaces supply, leading to increases in prices. In such a scenario, increased trade could lead to higher demand for labour, therefore reducing unemployment rates.

Suppose a country, let's call it 'Country A,' sees an inking in the demand for its goods from other nations as it is able to produce high-quality products at a reasonable cost. As a result, firms within Country A would require more labour to meet this increased demand, thereby reducing unemployment.

Core Concepts of Unemployment in International Trade

The relationship between unemployment and international trade becomes a bit more complex. Trade can affect the level of unemployment in a country depending on several factors including economic structure, labour market flexibility, and the type and composition of traded goods.

- Economic Structure : Countries focussed on manufacturing and industrial production may see a decrease in unemployment due to increase in foreign trade as they require a large workforce. However, countries focussed on services may not experience the same effect.

- Labour Market Flexibility : This refers to how easily labour can move between different sectors in a country. High labour market flexibility tends to result in lesser unemployment because workers can easily shift from sectors that are declining due to foreign trade to those that are booming.

- Type and Composition of Traded Goods : The impact of trade on unemployment can also significantly depend on the type and composition of goods being traded. For instance, if a country exports labour-intensive goods and imports capital-intensive ones, then foreign trade can reduce unemployment.

In other words, when evaluating the impact of trade on employment, it's essential to understand the structure and dynamics of the country's economy and the labour market. Furthermore, the type of goods and services traded also offer valuable insights.

Trade Equilibriums and Their Influence on Job Market

The relationship between trade and employment can be better understood with the concept of trade equilibrium. When a country reaches trade equilibrium, it's neither running a trade surplus nor a deficit, its import expenses equal export revenue. This balance can affect the job market in several ways.

Consider a scenario where a country's exports of goods and services surpass its imports (a trade surplus). This implies that the country's domestic industries are performing well, and thus there may be a high demand for labour to meet the production requirements which could reduce unemployment. However, if the country's exports decline and it ends up importing more than it exports (trade deficit), industries might lay off workers, leading to increased unemployment.

It is important to note that the impact of trade on employment is not static and changes over time as countries adapt to new technologies and shifts in global trade patterns. Thus, a full understanding of this dynamic relationship requires consistent study and analysis.

Trade Frictions and Unemployment: A Macroeconomic Analysis

A vital dimension in study of macroeconomics is understanding the impact of trade frictions on unemployment. Trade frictions, which refer to the various barriers and impediments to trade, are often a significant disruptive factor, capable of influencing labour market dynamics and, by extension, unemployment rates.

Causes and Consequences of Trade Frictions

Trade frictions can stem from numerous sources such as tariffs, quotas, trade restrictions, and even logistical challenges like inadequate infrastructure or inefficient customs procedures.

- Tariffs and Quotas : Imposed by governments to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. However, high tariffs and strict quotas can disrupt the flow of goods and services, leading to trade friction.

- Trade Restrictions : These include measures like embargos or boycotts. While they serve political or economic goals, they significantly hamper trade relations between nations.

- Inefficient Customs Procedures : These cause delays and increase costs associated with cross-border trade, thereby creating trade friction.

Trade Frictions: They refer to the various barriers and impediments to trade which can be policy-induced, like tariffs and quotas, or logistical, like inefficient customs procedures.

But what are the consequences of such frictions? The most immediate and observable impact is a reduction in the volume of trade between nations. Due to increased costs or complexities arising from these frictions, countries might find it less profitable to engage in international trade, leading to a decline in trade volumes.

A related consequence is that as trade volumes decrease, countries might turn inward and increase reliance on domestic industries. This re-orientation can lead to a change in the structure of an economy, often resulting in what's known as economic restructuring .

Impact of Trade Frictions on Unemployment

The influence of trade frictions on unemployment isn't straightforward and tends to be context-dependent. To put it simply, if trade frictions lead to limitations on imports and provoke an increase in domestic production, this might necessitate more labour thus reducing unemployment.

However, if the domestic industry isn't equipped to increase production or if the demand for domestic goods isn't strong enough to compensate for reduced trade, trade frictions might lead to stagnation and increased unemployment. This is particularly the case for economies heavily dependent on foreign trade. For instance, an export-led growth strategy would suffer tremendously under high trade friction scenarios, potentially leading to increased unemployment.

Historical Case Studies: Trade Frictions Leading to Unemployment

Historical cases offer invaluable insights into how trade frictions can lead to unemployment. For instance, consider the case of the automotive industry in the US in the 1980s. Japanese car manufacturers were outpacing their American counterparts, leading to increased imports of Japanese cars into the US. In response, the US imposed strict quotas on Japanese car imports to protect its domestic industry.

This led to a reduction in the total volume of cars being sold in the US, as Japanese manufacturers couldn't meet the high demand despite having the capacity to do so, and American manufacturers were not prepared to meet the excess demand. This mismatch led to a slowdown in the auto manufacturing industry, directly contributing to increased unemployment rates within the sector.

Another indicating case is the US-China trade war that started in 2018. This trade dispute, marked by high tariffs and trade restrictions imposed reciprocally, has had notable effects on unemployment.

Due to the tariffs, several industries in the US which relied on Chinese inputs saw their production costs rise sharply. Unable to pass on this increase in costs to consumers due to price sensitivity, many firms cut down on their workforce, thereby increasing unemployment.

These examples illustrate that trade frictions can indeed cause rises in unemployment levels. However, each situation is unique, and numerous variables come into play.

Investigating the Effects of Trade on Unemployment

Trade has a significant influence on unemployment rates across the globe. It's essential to examine this relationship closely to better comprehend the dynamics of international economies and understand the larger implications of trade policies. The effect of trade on unemployment is multifaceted and can be analysed from both positive and negative perspectives.

The Positive Effects of International Trade on Unemployment

International trade can play a vital role in reducing unemployment levels. By promoting economic activity and stimulating growth, trade can foster job creation and contribute to labour market stability. Here's how it accomplishes this:

- Increasing Demand: International trade allows countries to access larger markets, which can increase the demand for their goods and services. This elevated demand often necessitates an uptick in production levels, which can lead to job creation and subsequently lower unemployment rates.

- Fostering Economic Growth: Foreign trade can be a key driver of economic growth. By generating additional income and profits for businesses, trade can increase investment in capital and labour, thereby creating more job opportunities.

- Promoting Specialisation: International trade encourages nations to specialise in the production of goods and services they can produce more efficiently. By focusing on areas where they have a comparative advantage, countries can boost productivity, which may increase demand for specific skill sets and decrease unemployment rates within these sectors.

Additionally, international trade can lead to the transfer of technology and skills between countries. Technological advancements can result in upgraded industries which may need qualified workforce leading to a decrease in unemployment rates. However, this impact can be complex as it might also lead to job losses if certain skills become redundant due to technological upgrades.

Adverse Effects of Trade on Job Markets

While trade can bring about positive implications for unemployment, it can also produce adverse effects on job markets. Disruptions caused by global trade can lead to job displacements and increased unemployment rates.

- Structural Unemployment: International trade can result in structural changes to an economy, especially when a nation transitions from being primarily agricultural to increasingly industrial or service-oriented. These shifts may render some jobs obsolete, resulting in structural unemployment.

- Competition and Downsizing: Increased competition from international markets can make it difficult for domestic firms to compete. This pressure can lead businesses to downsize their operations or even shut down, causing job losses.

- Trade Deficits: When a country consistently imports more than it exports, it could witness a significant outflow of capital, which may in turn limit the growth of domestic industries and lead to higher unemployment.

Moreover, not all job losses can be recouped by creating new roles in other sectors. Workers who lose their jobs may not possess the skills needed for new industries or may live in areas where job opportunities are scarce. In such instances, trade can contribute to sustained high unemployment rates.

A Comparative Study: Effects of Local and International Trade on Unemployment

Focussing on the comparison between the effects of local and international trade on unemployment reveals compelling insights. Local trade, or trade within a country's borders, may not have the same impact as international trade due to distinct dynamics.

Local trade, by its very nature, limits exposure to global competitive pressures. Domestic firms primarily compete with other domestic firms. While competition exists, it's often mitigated by common regulations, standards and costs. Therefore, local trade might not have the same level of job displacement as seen in international trade. However, evolutions in local markets could still lead to some job losses as industries expand, contract or evolve.

On the other hand, international trade leads to direct competition between domestic firms and foreign counterparts. This competition can be more intense due to factors like varying costs of labour, diverse regulations and standards, and different levels of access to technologies or resources. Hence, the potential for job displacement and unemployment can be higher. However, international trade also offers opportunities for job creation that might not be accessible through local trade alone. In essence, the comparative effects of local and international trade on unemployment are contingent on numerous factors.

Causes of Trade and Unemployment: A Comprehensive Discussion

Trade and unemployment, two critical aspects of macroeconomics, are affected by a wide array of factors. From trade policies and economic conditions to globalisation and technological advancements, a variety of elements shape the intricate dynamics of trade and unemployment. Let's delve deeper into these causative factors.

Understanding the Relationship Between Trade Policies and Unemployment

Trade policies are one of the key variables that shape the landscape of international trade and have consequential impacts on unemployment levels. These policies, which can range from tariffs and import quotas to economic sanctions and export subsidies, can influence how and to what extent countries engage in international trade.

Consider tariffs , which are essentially taxes imposed on imported goods. High tariffs can make imported goods more expensive, encouraging consumers to buy domestically produced goods instead. This increased demand for local products could stimulate domestic industry and potentially increase employment. In fact, the economic model known as the Stolper-Samuelson theorem holds that import restrictions, such as tariffs, can result in higher real wages for individuals working in sectors that produce protected goods. However, this theorem assumes that resources, including labour, can freely move between sectors - an assumption that doesn't always hold in reality.

Import quotas , which directly limit the quantity of a certain good that can be imported, can have a similar impact. By reducing competition from foreign goods, import quotas allow domestic industries to sell more, which could theoretically increase employment levels in these sectors.

However, the effects of trade policies on unemployment are not always positive. Economic sanctions , for example, can severely restrict a country’s ability to trade and often lead to increases in unemployment. Similarly, export subsidies may initially boost employment in the subsidized industry. Still, they can lead to inefficiencies and long-term negative impacts on employment by allocating resources away from more productive areas of the economy.

Protectionist Policies : These are measures taken by a government to restrict or restrain international trade, often with the intent of protecting local businesses and jobs from foreign competition. Policies such as tariffs and quotas can, however, distort trade and reduce economic efficiency.

Macroeconomic Factors Influencing Trade and Unemployment

Several macroeconomic factors also feed into the relationship between trade and unemployment. These include currency exchange rates, inflation, fiscal and monetary policy, technological changes, and business cycles, to mention a few.

The exchange rate of a country's currency can have a profound impact on its international trade. When a currency is strong compared to that of its trading partners, its exports become more expensive, and imports become cheaper. This situation can lead to a decrease in demand for domestically produced goods and, consequently, a potential increase in unemployment.

Inflation also plays a part. Higher prices can make a country's exports less competitive on the international market, dampening demand for these goods and leading to lower levels of production and possible layoffs. Similarly, the economic policies of a country, including fiscal and monetary policies, can affect trade and unemployment. For instance, high interest rates can reduce domestic investment, stifery economic growth, and increase unemployment rates.

The business cycle , which refers to the fluctuations in economic activity over time, can also influence trade and unemployment. During downturns of the business cycle, demand for goods and services often declines, leading to reduced trade and increased unemployment.

Technological changes can also have significant effects on trade and unemployment. Technological advancements that improve productivity can boost a country's exports and potentially increase employment in sectors that adopt these technologies. However, technological changes can also make certain jobs obsolete, leading to increased unemployment in affected industries.

The Role of Globalisation in Trade and Unemployment

Globalisation has been a transformative force in shaping trade and unemployment patterns around the world over the past few decades. Globalisation, which can broadly be understood as the increased interconnectedness and interdependence of the world's economies, is closely intertwined with changes in trade and unemployment.

From a trade perspective, globalisation has led to a dramatic increase in international trade volumes. As barriers to trade have come down, and transport and communication technologies have evolved, goods, services, and capital now flow more freely across borders than ever before. This phenomenon has led to increased competition, industry realignment and, importantly for our discussion, changes in employment patterns.

The impact of globalisation on employment is multifaceted. New trade opportunities facilitated by globalisation can create jobs in certain sectors, contributing to a decrease in unemployment levels. However, competition from inexpensive imports can cause domestic industries to contract, leading to job losses and potential increases in unemployment.