Thesis and Purpose Statements

Use the guidelines below to learn the differences between thesis and purpose statements.

In the first stages of writing, thesis or purpose statements are usually rough or ill-formed and are useful primarily as planning tools.

A thesis statement or purpose statement will emerge as you think and write about a topic. The statement can be restricted or clarified and eventually worked into an introduction.

As you revise your paper, try to phrase your thesis or purpose statement in a precise way so that it matches the content and organization of your paper.

Thesis statements

A thesis statement is a sentence that makes an assertion about a topic and predicts how the topic will be developed. It does not simply announce a topic: it says something about the topic.

Good: X has made a significant impact on the teenage population due to its . . . Bad: In this paper, I will discuss X.

A thesis statement makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of the paper. It summarizes the conclusions that the writer has reached about the topic.

A thesis statement is generally located near the end of the introduction. Sometimes in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or an entire paragraph.

A thesis statement is focused and specific enough to be proven within the boundaries of the paper. Key words (nouns and verbs) should be specific, accurate, and indicative of the range of research, thrust of the argument or analysis, and the organization of supporting information.

Purpose statements

A purpose statement announces the purpose, scope, and direction of the paper. It tells the reader what to expect in a paper and what the specific focus will be.

Common beginnings include:

“This paper examines . . .,” “The aim of this paper is to . . .,” and “The purpose of this essay is to . . .”

A purpose statement makes a promise to the reader about the development of the argument but does not preview the particular conclusions that the writer has drawn.

A purpose statement usually appears toward the end of the introduction. The purpose statement may be expressed in several sentences or even an entire paragraph.

A purpose statement is specific enough to satisfy the requirements of the assignment. Purpose statements are common in research papers in some academic disciplines, while in other disciplines they are considered too blunt or direct. If you are unsure about using a purpose statement, ask your instructor.

This paper will examine the ecological destruction of the Sahel preceding the drought and the causes of this disintegration of the land. The focus will be on the economic, political, and social relationships which brought about the environmental problems in the Sahel.

Sample purpose and thesis statements

The following example combines a purpose statement and a thesis statement (bold).

The goal of this paper is to examine the effects of Chile’s agrarian reform on the lives of rural peasants. The nature of the topic dictates the use of both a chronological and a comparative analysis of peasant lives at various points during the reform period. . . The Chilean reform example provides evidence that land distribution is an essential component of both the improvement of peasant conditions and the development of a democratic society. More extensive and enduring reforms would likely have allowed Chile the opportunity to further expand these horizons.

For more tips about writing thesis statements, take a look at our new handout on Developing a Thesis Statement.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Seeking Feedback from Others

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

Learning objectives.

- Identify the four common academic purposes.

- Identify audience, tone, and content.

- Apply purpose, audience, tone, and content to a specific assignment.

Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. One technique that effective writers use is to begin a fresh paragraph for each new idea they introduce.

Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks. One paragraph focuses on only one main idea and presents coherent sentences to support that one point. Because all the sentences in one paragraph support the same point, a paragraph may stand on its own. To create longer assignments and to discuss more than one point, writers group together paragraphs.

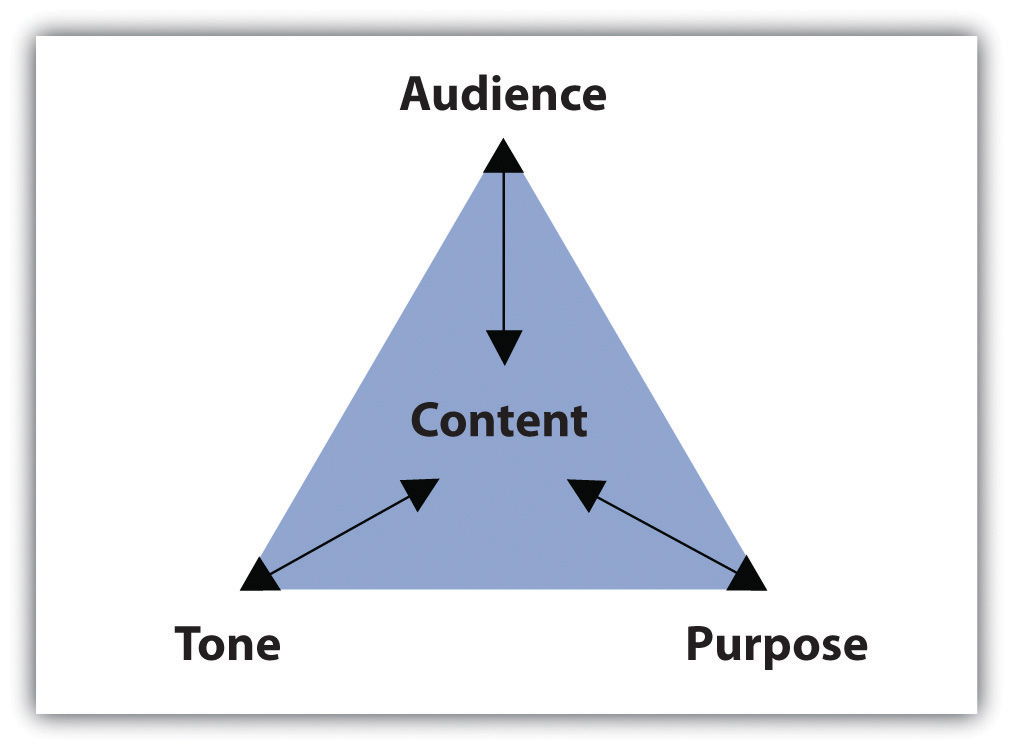

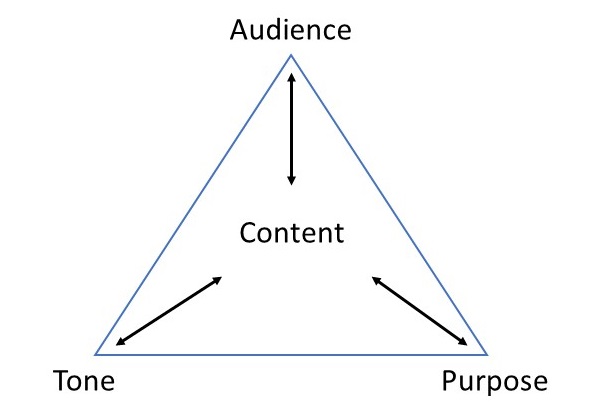

Three elements shape the content of each paragraph:

- Purpose . The reason the writer composes the paragraph.

- Tone . The attitude the writer conveys about the paragraph’s subject.

- Audience . The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

Figure 6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content Triangle

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what the paragraph covers and how it will support one main point. This section covers how purpose, audience, and tone affect reading and writing paragraphs.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write a particular document. Basically, the purpose of a piece of writing answers the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing fulfill four main purposes: to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate. You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure. Because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. To learn more about reading in the writing process, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Eventually, your instructors will ask you to complete assignments specifically designed to meet one of the four purposes. As you will see, the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of the paper, helping you make decisions about content and style. For now, identifying these purposes by reading paragraphs will prepare you to write individual paragraphs and to build longer assignments.

Summary Paragraphs

A summary shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials. You probably summarize events, books, and movies daily. Think about the last blockbuster movie you saw or the last novel you read. Chances are, at some point in a casual conversation with a friend, coworker, or classmate, you compressed all the action in a two-hour film or in a two-hundred-page book into a brief description of the major plot movements. While in conversation, you probably described the major highlights, or the main points in just a few sentences, using your own vocabulary and manner of speaking.

Similarly, a summary paragraph condenses a long piece of writing into a smaller paragraph by extracting only the vital information. A summary uses only the writer’s own words. Like the summary’s purpose in daily conversation, the purpose of an academic summary paragraph is to maintain all the essential information from a longer document. Although shorter than the original piece of writing, a summary should still communicate all the key points and key support. In other words, summary paragraphs should be succinct and to the point.

A summary of the report should present all the main points and supporting details in brief. Read the following summary of the report written by a student:

Notice how the summary retains the key points made by the writers of the original report but omits most of the statistical data. Summaries need not contain all the specific facts and figures in the original document; they provide only an overview of the essential information.

Analysis Paragraphs

An analysis separates complex materials in their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. The analysis of simple table salt, for example, would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride, which is also called simple table salt.

Analysis is not limited to the sciences, of course. An analysis paragraph in academic writing fulfills the same purpose. Instead of deconstructing compounds, academic analysis paragraphs typically deconstruct documents. An analysis takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

Take a look at a student’s analysis of the journal report.

Notice how the analysis does not simply repeat information from the original report, but considers how the points within the report relate to one another. By doing this, the student uncovers a discrepancy between the points that are backed up by statistics and those that require additional information. Analyzing a document involves a close examination of each of the individual parts and how they work together.

Synthesis Paragraphs

A synthesis combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Consider the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of the synthesizer is to blend together the notes from individual instruments to form new, unique notes.

The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document. An academic synthesis paragraph considers the main points from one or more pieces of writing and links the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Take a look at a student’s synthesis of several sources about underage drinking.

Notice how the synthesis paragraphs consider each source and use information from each to create a new thesis. A good synthesis does not repeat information; the writer uses a variety of sources to create a new idea.

Evaluation Paragraphs

An evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday experiences are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge. For example, at work, a supervisor may complete an employee evaluation by judging his subordinate’s performance based on the company’s goals. If the company focuses on improving communication, the supervisor will rate the employee’s customer service according to a standard scale. However, the evaluation still depends on the supervisor’s opinion and prior experience with the employee. The purpose of the evaluation is to determine how well the employee performs at his or her job.

An academic evaluation communicates your opinion, and its justifications, about a document or a topic of discussion. Evaluations are influenced by your reading of the document, your prior knowledge, and your prior experience with the topic or issue. Because an evaluation incorporates your point of view and reasons for your point of view, it typically requires more critical thinking and a combination of summary, analysis, and synthesis skills. Thus evaluation paragraphs often follow summary, analysis, and synthesis paragraphs. Read a student’s evaluation paragraph.

Notice how the paragraph incorporates the student’s personal judgment within the evaluation. Evaluating a document requires prior knowledge that is often based on additional research.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate . Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Read the following paragraphs about four films and then identify the purpose of each paragraph.

- This film could easily have been cut down to less than two hours. By the final scene, I noticed that most of my fellow moviegoers were snoozing in their seats and were barely paying attention to what was happening on screen. Although the director sticks diligently to the book, he tries too hard to cram in all the action, which is just too ambitious for such a detail-oriented story. If you want my advice, read the book and give the movie a miss.

- During the opening scene, we learn that the character Laura is adopted and that she has spent the past three years desperately trying to track down her real parents. Having exhausted all the usual options—adoption agencies, online searches, family trees, and so on—she is on the verge of giving up when she meets a stranger on a bus. The chance encounter leads to a complicated chain of events that ultimately result in Laura getting her lifelong wish. But is it really what she wants? Throughout the rest of the film, Laura discovers that sometimes the past is best left where it belongs.

- To create the feeling of being gripped in a vice, the director, May Lee, uses a variety of elements to gradually increase the tension. The creepy, haunting melody that subtly enhances the earlier scenes becomes ever more insistent, rising to a disturbing crescendo toward the end of the movie. The desperation of the actors, combined with the claustrophobic atmosphere and tight camera angles create a realistic firestorm, from which there is little hope of escape. Walking out of the theater at the end feels like staggering out of a Roman dungeon.

- The scene in which Campbell and his fellow prisoners assist the guards in shutting down the riot immediately strikes the viewer as unrealistic. Based on the recent reports on prison riots in both Detroit and California, it seems highly unlikely that a posse of hardened criminals will intentionally help their captors at the risk of inciting future revenge from other inmates. Instead, both news reports and psychological studies indicate that prisoners who do not actively participate in a riot will go back to their cells and avoid conflict altogether. Examples of this lack of attention to detail occur throughout the film, making it almost unbearable to watch.

Collaboration

Share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing at Work

Thinking about the purpose of writing a report in the workplace can help focus and structure the document. A summary should provide colleagues with a factual overview of your findings without going into too much specific detail. In contrast, an evaluation should include your personal opinion, along with supporting evidence, research, or examples to back it up. Listen for words such as summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate when your boss asks you to complete a report to help determine a purpose for writing.

Consider the essay most recently assigned to you. Identify the most effective academic purpose for the assignment.

My assignment: ____________________________________________

My purpose: ____________________________________________

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions.

For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send e-mails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with her intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own paragraphs, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject. Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience would not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

- Demographics. These measure important data about a group of people, such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

- Education. Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

- Prior knowledge. This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

- Expectations. These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance, such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

On your own sheet of paper, generate a list of characteristics under each category for each audience. This list will help you later when you read about tone and content.

1. Your classmates

- Demographics ____________________________________________

- Education ____________________________________________

- Prior knowledge ____________________________________________

- Expectations ____________________________________________

2. Your instructor

3. The head of your academic department

4. Now think about your next writing assignment. Identify the purpose (you may use the same purpose listed in Note 6.12 “Exercise 2” ), and then identify the audience. Create a list of characteristics under each category.

My audience: ____________________________________________

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Keep in mind that as your topic shifts in the writing process, your audience may also shift. For more information about the writing process, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Also, remember that decisions about style depend on audience, purpose, and content. Identifying your audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how you write, but purpose and content play an equally important role. The next subsection covers how to select an appropriate tone to match the audience and purpose.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit through writing a range of attitudes, from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers intimate their attitudes and feelings with useful devices, such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just 7 percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelt and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.

Think about the assignment and purpose you selected in Note 6.12 “Exercise 2” , and the audience you selected in Note 6.16 “Exercise 3” . Now, identify the tone you would use in the assignment.

My tone: ____________________________________________

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. Consider that audience of third graders. You would choose simple content that the audience will easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone. The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Match the content in the box to the appropriate audience and purpose. On your own sheet of paper, write the correct letter next to the number.

- Whereas economist Holmes contends that the financial crisis is far from over, the presidential advisor Jones points out that it is vital to catch the first wave of opportunity to increase market share. We can use elements of both experts’ visions. Let me explain how.

- In 2000, foreign money flowed into the United States, contributing to easy credit conditions. People bought larger houses than they could afford, eventually defaulting on their loans as interest rates rose.

- The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, known by most of us as the humungous government bailout, caused mixed reactions. Although supported by many political leaders, the statute provoked outrage among grassroots groups. In their opinion, the government was actually rewarding banks for their appalling behavior.

Audience: An instructor

Purpose: To analyze the reasons behind the 2007 financial crisis

Content: ____________________________________________

Audience: Classmates

Purpose: To summarize the effects of the $700 billion government bailout

Audience: An employer

Purpose: To synthesize two articles on preparing businesses for economic recovery

Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone from Note 6.18 “Exercise 4” , generate a list of content ideas. Remember that content consists of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations.

My content ideas: ____________________________________________

Key Takeaways

- Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks of information.

- The content of each paragraph and document is shaped by purpose, audience, and tone.

- The four common academic purposes are to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate.

- Identifying the audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how and what you write.

- Devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language communicate tone and create a relationship between the writer and his or her audience.

- Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations. All content must be appropriate and interesting for the audience, purpose and tone.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

When You Write

What is the Author’s Purpose & Why Does it Matter?

There’s always a reason a writer decides to produce their work. We rarely think about it, but there’s always a motivating factor behind intent and goals they hope to achieve.

This “why” behind the author’s writing is what we call the author’s purpose, and it is the reason the author decided to write about something.

There are billions—maybe more—of reasons a writer decides to write something and when you understand the why behind the words, you can effectively and accurately evaluate their writing.

When you understand the why, you can apprehend what the author is trying to say, grasp the writer’s message, and the intent of a particular piece of literary work.

Without further ado, let me explain what the author’s purpose is and how you can identify it.

What is Author’s Purpose?

Just as I introduced the term, an author’s purpose is the author’s reason for or intent in writing.

In both fiction and non-fiction, the author selects the genre, writing format, and language to suit the author’s purpose.

The writing formats, genres, and vernacular are chosen to communicate a key message to the reader, to entertain the reader, to sway the reader’s opinion, et cetera.

The way an author writes about a topic fulfills their purpose; for example, if they intend to amuse, the writing will have a couple of jokes or anecdotal sections. The author’s purpose is also reflected in the way they title their works, write prefaces, and in their background.

In general, the purposes fall into three main categories, namely persuade, inform, and entertain. The three types of author’s purpose make the acronym PIE.

But, there are many reasons to write, the PIE just represents the three main classes of the author’s purpose .

In the next section, I’m going to elaborate on the various forms of the author’s purpose including the three broader categories that I have introduced.

How useful is the Author’s Purpose?

Understanding the author’s purpose helps readers understand and analyze writing. This analytical advantage helps the reader have an educated point of view. Titles or opening passages act as the text’s signposts, and we can assume what type of text we’re about to read.

If you can identify the author’s purpose, it becomes easier to recognize the proficiencies used to achieve that particular purpose. So, once you identify the author’s purpose, you can recognize the style, tone, word, and content used by the author to communicate their message.

You also get to explore other people’s attitudes, beliefs, or perspectives.

Why does the Author’s Purpose Matter for the Writer?

The intent and manner in which a body of text is written determine how one perceives the information one reads.

Perception is especially important if the author aims to inform, educate, or explain something to the reader. For instance, an author writing an informative piece should provide relevant or reliable information and clearly explain his concepts; otherwise, the reader will think they are trying to be deceptive.

The readers—particularly those reading informative or persuasive pieces—expect authors to support their arguments and demonstrate validity by using autonomous sources as references for their writing.

Likewise, readers expect to be thoroughly entertained by works of fiction.

Types of Author’s Purpose

Mostly, reasons for writing are condensed into 5 broad categories, and here they are:

1. to Persuade

Using this form of author’s purpose, the author tries to sway the reader and make them agree with their opinion, declaration, or stance. The goal is to convince the reader and make them act in a specific way.

To convince a reader to believe a concept or to take a specific course of action, the author backs the idea with facts, proof, and examples.

Authors also have to be creative with their persuasive writing . For instance, apart from form complementary facts and examples, the author has to borrow some forms of entertaining elements and amuse their readers. This makes their writing enjoyable and relatable to some extent, increasing the likelihood of persuading people to take the required course of action.

2. to Inform

When the author’s purpose is to inform or teach the reader, they use expository writing. The author attempts to teach objectively by showing or explaining facts.

When you look at informative writing and persuasive writing, you can identify a common theme: the use of facts. However, the two forms of the author’s purpose use these facts differently. Unlike persuasive writing, which uses facts to convince the reader, informative writing uses facts to educate the reader about a particular subject. With persuasive writing, it’s like there’s a catch: the call to action. But, informative writing only uses facts to educate the reader, not to convince them to take a specific course of action.

Informative writing only seeks to “expose” factual information about a topic for enlightenment.

3. to Entertain

Most fiction books are written to entertain the reader—and, yes, including horror. On the other hand, non-fiction works combine an entertaining element with informative writing.

To entertain, the author tries to keep things as interesting as possible by coming up with fascinating characters , exciting plots, thrilling storylines, and sharp dialogue.

Most narratives, poetry, and plays are written to entertain. Be that as it may, these works of fiction can also be persuasive or informative, but if we fuse values and ideas, changing the reader’s perspective becomes an easier task.

Nonetheless, the entertaining purpose has to dominate, or else, readers are going to lose interest quickly and the informative purpose will be defeated.

4. to Explain

When the author’s purpose is to explain, they write with the intent of telling the reader how to do something or giving details on how something works.

This type of writing is about teaching a method or a process and the text contains explanations that teach readers how a particular process works or the procedure required to do or create something.

5. to Describe

When describing is the author’s purpose, the author uses words to complement images in describing something. This type of writing attempts to give a more detailed description of something, a bit more detail than the “thousand words that a picture paints.”

The writer uses adjectives and images to make the reader feel as though it were their own sensory experience.

Main elements and examples of Author’s Purpose

A great way to identify the author’s purpose is to analyze the whole piece of literature. The first step would be to ask “What is the point of this piece?” One can also look at why it was written, who it was written for, and what effect they wanted it to have on readers.

Another method is to break down the text into different categories of purpose. For example, if someone wants their writing to persuade, they would use rhetorical devices (i.e., logical appeals).

Below are the types of publications dominated by each purpose and the things to look for when identifying the author’s purpose.

Persuasive Purpose

Persuasion is usually found in non-fiction, but countless other fiction books have also been used to persuade the reader.

Propaganda works are top of the list when it comes to persuasion in writing. But we also have other works including:

- Political speeches

- Advertisements

- Infomercial scripts and news editorials meant to persuade the reader

- Fiction writing whose author has an agenda

How to Identify Persuasive Purpose

When trying to identify persuasion in writing, you should ask yourself if the author is attempting to convince the reader to take a specific course of action.

If the author is trying to persuade their readers, they employ several tactics and schemes including hyperboles, forceful phrases, repetition, supporting evidence, imagery, and photographs, and they attack opposing ideas or proponents.

Informative Purpose

Although some works of fiction are also informative, informative writing is commonly found on non-fiction shelves and dominates academic works.

Many types of academic textbooks are written with the primary purpose of informing the reader.

Informative writing is generally found in the following:

- Textbooks

- Encyclopedias

- Recipe books

How to identify Informative Purpose

Just like in persuasive writing, the writer will attempt to inform the reader by feeding them facts.

So, how can you spot a pure intent to inform?

The difference between the two is that an author whose purpose is persuasion is likely going to provide the reader with some facts in an attempt with the primary goal of convincing the reader of the worthwhileness or valuableness of a particular idea, item, situation, et cetera.

On the other hand, in informative writing, facts are used to inform and are not sugar-coated by the author’s opinion, like is the case when the author’s purpose is to persuade.

Entertaining Purpose

The entertaining purpose dominates fiction writing—there’s a huge emphasis placed on entertaining the reader in almost every fiction book.

In almost every type of fiction (be it science fiction, romance, or fantasy), the writer works on an exciting story that will leave his readers craving for more.

The only issue with this purpose is that the adjective ‘entertaining’ is subjective and what entertains one reader may not be so riveting for another.

For example, the type of ‘entertainment’ one gets from romance novels is different from the amusement another gets from reading science fiction.

Although entertainment in writing is mostly used in fiction, non-fiction works also use storytelling—now and then—to keep the reader engaged and drive home a specific point.

How to identify Entertaining Purpose

Identifying works meant to entertain is fairly easy: When an author intends to entertain or amuse the reader, they use a variety of schemes aimed at getting the readers engaged.

The author may insert some humor into their narrative or use dialogue to weave in some jokes.

The writer may also use cliffhangers at the end of a page or chapter to keep the reader interested in the story.

Explaining Purpose

Authors also write to explain a topic or concept, especially in the non-fiction category. Fiction writers also write to explain things, usually not for the sole purpose of explaining that topic, but to help readers understand the plot, an event, a setting, or a character.

This type of purpose is dominant in How-to books, texts with recipes, DIY books, company or school books for orientation, and others.

How to identify Explaining Purpose

Texts with explaining purpose typically have a list of points (using a numbered or bulleted format), use infographics, diagrams, or illustrations.

Explaining purpose also contains a lot of verbs that try to convey directions, instructions, or guidelines.

Every author’s purpose or motive should be more than just entertaining the reader, it should be about more than just telling a good story.

A lot of authors tell stories to accomplish different objectives – some want to teach, provoke thought and debate, or show people that they’re not alone in their struggles. Others—like yours truly—write an article about the different types of Author’s purpose and hope it changes your writing style accordingly.

Authors must take their audience’s needs and interests into account, as well as their purposes for writing when writing something they intend to publish.

The author should find a way to make a piece that both generates interest as well as provides value to their reader.

Recommended Reading...

4 things that will improve your writing imagination, how to write an affirmation, best cities for writers to live and write in, list of interesting places to write that evoke inspiration.

Keep in mind that we may receive commissions when you click our links and make purchases. However, this does not impact our reviews and comparisons. We try our best to keep things fair and balanced, in order to help you make the best choice for you.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

© 2024 When You Write

21 Author’s Purpose Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

The author’s purpose of a text refers to why they wrote the text .

It;s important to know the author’s purpose for a range of reasons, including:

- Media Literacy : We want to make sure we’re not tricked by the author. When reading an article online, for example, we want to figure out what the author’s purpose is in order to determine whether they’re going to write with a particular political bias.

- Determining Meaning: We might also want to know the author’s purpose in order to infer and predict what the underlying message might be. If an author’s job is to inform, we can read the text closely in order to examine its logic; but if the purpose is to entertain, we can consume the text with less of a critical lens.

- Understand Genre Convention : If we know the author’s purpose, we can predict and develop expectations about how the piece will be written. For example, persuasive texts should cite sources, while in reflective texts, we should expect first-person language and more intimate language.

Below are a range of possible purposes that authors may have when writing texts.

Author’s Purpose Examples

1. to inform.

Common Text Genres: News articles, Research papers, Textbooks, Biographies, Manuals.

Texts designed to inform tend to seek an objective stance, where the author presents facts, data, or truths to the reader with the sole intention of educating or delivering important information to the reader. It is common, for example, in news articles, where journalists must adhere to journalistic ethics and ensure the information is entirely factual. This is also often the purpose of non-fiction books, academic writing, scientific articles, and of course, this very website you’re reading right now.

Example of an Informative Text A National Geographic article on climate change informs readers about the state of the planet, providing facts and figures about global warming, melting ice caps, and so on.

2. To Entertain

Common Text Genres: Novels, Short stories, Poetry, Plays, Comics

This type of writing is meant to captivate the reader’s imagination and provide enjoyment. Here, the content needs to be delivered in a way that doesn’t bore and keeps the reader compelled to keep reading. To do this, the writing might be humorous, suspenseful, mysterious, or touching, depending on the genre. The author may also create characters, plot, and settings to keep the reader engaged and entertained, as with novels.

Example of an Entertaining Text A well-known example is J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series, which was written with the primary goal of entertaining readers with its magical world and captivating story.

3. To Persuade

Common Text Genres: Advertisements, Speeches, Opinion columns, Cover letters, Product reviews

In persuasive texts, the author’s main purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular point of view or to take a specific action. This involves the use of arguments, logic, evidence, and emotional appeals. Persuasive writing can be found in speeches, advertisements, and opinion editorials. To examine some key techniques and strategies authors use to persuade, consult my article on the thirty types of persuasion in literature .

Example of a Persuasive Text A classic example is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he persuasively argues for the end of racial discrimination in the United States.

4. To Describe

Common Text Genres: Travelogues, Food reviews, Personal essays, Descriptive poetry, Nature writing

Descriptive texts aim to paint a vivid picture in the reader’s mind. These sorts of texts can take us away to a different place and draw us into a complex world created by the author. For example, the author uses detailed and evocative descriptions to convey a scene, object, person, or feeling. The goal is to make the reader see, hear, smell, taste, or feel what is being described. This can be seen in many forms of writing, but is most evident in fiction, poetry, and travel writing, and can be paired with other author purposes, such as entertainment.

Example of a Descriptive Text An example of descriptive writing is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”, especially in its portrayal of the extravagant lifestyle of Jay Gatsby.

5. To Explain

Common Text Genres: How-to articles, Technical manuals, FAQs, Cookbooks, Explanatory journalism

In this type of writing, the author seeks to make the reader understand a process, concept, or idea. The writing breaks down complex subjects into simpler, more digestible parts. The author provides step-by-step explanations, examples, and definitions to aid understanding. This can be seen in how-to guides, tutorials, and expository essays . Of course, this purpose overlaps significantly with to inform , but tends to be more step-by-step or strips complex ideas into clear-to-understand chunks of information .

Example of an Explanatory Text A real-world example is Stephen Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time”, in which complex topics such as the Big Bang, black holes, and light cones are explained in a manner accessible to non-scientists.

6. To Analyze

Common Text Genres: Critical essays, Business reports, Scientific research papers, Market research, Literary analysis

Authors who write to analyze seek to break down a complex concept, event, or piece of work into smaller parts in order to better understand it. Analytical writing looks closely at all the components of a topic and how they work together. It’s about making connections and recognizing patterns. It could, for example, aim to identify flaws in a topic, or draw connections, similarities and differences, between multiple different concepts. You’ll commonly find these types of texts in professional contexts, such as reports provided to a company to give them guidance that helps them make better business decisions.

Example of an Analytical Text “The Art of War” by Sun Tzu offers a comprehensive analysis of warfare strategies, breaking down the complexities of warfare into key principles.

7. To Teach

Common Text Genres: Textbooks, How-to guides, Cookbooks, Self-help books

The author aims to impart knowledge or skills to the reader. These texts often provide step-by-step instructions or delve deep into a topic to ensure understanding. The goal is not only to inform but to enable the reader to perform a task or understand a concept independently. Examples of texts like this can include self-help books and textbooks, which might also contain ‘tasks’, ‘homework’ or ‘revision quizzes’ at the end of each chapter.

Example of an Educational Text “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft” by Stephen King teaches readers about the art of writing and the life of a writer.

8. To Argue

Common Text Genres: Opinion editorials, Political speeches, Legal briefs, Persuasive essays

For these sorts of texts, the author’s purpose is to persuade the reader to accept a particular perspective, worldview, or ideology, often presenting a thesis and supporting it with evidence and logical reasoning. The goal is to make a case and convince the reader of its validity. Authors could use pathos , meaning emotion , to argue a point (e.g. appealing to a person’s emotional side), or logos , meaning logic (e.g. setting out a clear and logical explanation of why the author’s perspective is correct).

Example of an Argumentative Text A famous example is “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” by Mary Wollstonecraft, where she argues for women’s rights and equality.

9. To Inspire

Common Text Genres: Motivational speeches, Inspirational books, Success stories, Motivational posters

Authors with this purpose want to stimulate their readers to act or create a change, instill hope, or provoke a sense of awe. These writings often share success stories, motivational thoughts, or beautiful descriptions of nature or humanity. A wide range of texts aim to inspire, from novels about amazing journeys, biographies about great people from history, and even people writing sales copy for brands.

Example of an Inspirational Text “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” by Maya Angelou is a work meant to inspire readers through its tale of overcoming adversity.

10. To Reflect

Common Text Genres: Diaries or journals, Vlogs and blogs, Retirement speeches, Reflective essays

In a reflective piece, the aim of the author is to share personal experiences, thoughts, or insights in an introspective manner. The goal is to convey the author’s personal journey or internal thought process. These texts often give readers a window into the author’s mind, and they may invite readers to reflect on their own experiences as well. Sometimes, the author will write the piece as a tool for self-improvement , such as to identify where they made mistakes or weaknesses in their processes, so they don’t make those mistakes next time.

Example of a Reflective Text “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius is a series of personal writings, reflecting the author’s stoic philosophy and ideas on life.

11. To Share

Common Text Genres: Personal Blogs, Social Media Posts, Personal Essays, Anecdotes , Letters.

In this type of writing, the author aims to share personal experiences, thoughts, ideas, or information with the reader. The writer may offer insights into their lives, discuss their passions, or recount an event that happened to them. We might see this, for example, for someone who writes detailed reflections on their travels in their travel blog, or even a personal email back to friends and family each week.

Example of a Text designed to Share Elizabeth Gilbert’s “Eat, Pray, Love” is a memoir where the author shares her journey of self-discovery as she travels through Italy, India, and Indonesia.

12. To Record

Common Text Genres: Historical Accounts, Diaries, Journals, Biographies, Documentaries.

When writing to record, the author aims to create a detailed and factual account of events or experiences, either for personal reflection or to inform future generations. This type of writing can also serve to preserve personal or historical memories. We see this, for example, in historians’ writing as well as in some journalistic work, such as in the New York Times, which has become known as the paper of record for its longevity in recording important moments in US history.

Example of a Text of Record Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” is a historical record of her experiences hiding during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

13. To Provoke Thought

Common Text Genres: Philosophical Works, Thought-Provoking Novels, Reflective Essays, Social Commentaries.

Authors who write to provoke thought aim to challenge their readers, pushing them to think more deeply about certain topics or to see things from a different perspective. They may raise complex questions, explore ambiguities, or critique societal norms. Such authors might be even aiming to get the reader upset, animated, or otherwise achieving cognitive dissonance in order to shift their thinking in some way.

Example of a Thought-Provoking Text George Orwell’s “1984” provokes thought about totalitarianism, surveillance, and individual freedom.

14. To Criticize

Common Text Genres: Reviews, Critical Essays, Satire, Polemics, Critiques .

When authors write to criticize, their aim is to express disapproval, dissent, or disagreement. They may critique a person, an idea, a societal trend, a piece of work, etc. They typically present their criticisms in a structured, reasoned manner, often supported by evidence. We see this regularly, for example, in ‘letters to the editor’ in newspapers, where everyday people can write into a newspaper in order to share their thoughts or rants for everyone to read.

Example of a Critical Text In his essay “Self-Reliance,” Ralph Waldo Emerson criticizes societal conformity and advocates for individualism.

15. To Predict

Common Text Genres: Speculative Fiction, Futurism Articles, Predictive Analytics Reports, Science Fiction.

Authors who write to predict aim to forecast future events or trends. These predictions could be based on current data, societal trends, scientific understanding, or simply imaginative speculation. This can be anything from a piece written by an economist or political scientist who’s predicting social trends that are upcoming, to a sci-fi novel that attempts to predict a dystopian future where AI has taken over the world!

Example of a Predictive Text In Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” the author predicts a future society characterized by technological advancements, consumerism, and a lack of individual freedom.

16. To Express Emotion

Common Text Genres: Poetry, Personal Essays, Novels, Letters, Memoirs.

When authors write to express emotion, their main goal is to convey their feelings, or the feelings of someone else, to the reader. They might explore their emotional reaction to events, or evoke emotion in the reader. This is a common purpose of poetry and song lyrics, which have long genre-histories of evoking emotions in audiences, especially when the lyrics are read or sung to a live audience.

Example of an Emotional Text Sylvia Plath’s poetry, such as in her collection “Ariel,” often expresses deep personal emotions, particularly her struggles with depression.

17. To Explore

Common Text Genres: Adventure Novels, Travel Writing, Scientific Papers, Experimental Poetry, Philosophy Books.

Authors who write to explore aim to delve deeply into a topic, concept, or place. This might involve exploring physical environments, such as in travel writing, or abstract concepts , as in philosophical or scientific texts. Exploratory writing may start without a clear end-goal, and can ramble its way to an unknown conclusion.

Example of an Exploratory Text Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” explores the concept of natural selection and evolution.

18. To Satirize

Common Text Genres: Satirical Novels, Political Cartoons, Satirical Essays, Parodies.

Satirical writing uses humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other societal issues. It could, for example, be a satirical novel which tries to undermine or make a joke out of other famous texts or genres. This, obviously, overlaps with the author purpose of to entertain but may also have elements of social commentary.

Example of a Satirical Text Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” satirizes human nature and the “travelers’ tales” literary subgenre.

19. To Commemorate

Common Text Genres: Eulogies, Obituaries, Commemorative Speeches, Historical Fiction.

Writing to commemorate aims to honor or remember a person, event, or idea. It often involves highlighting the subject’s significance or impact. For example, a person might write a piece that commemorates veterans on Vetertan’s Day. Similarly, an obituary commemorates a person’s life and attempts to sum up their achievements and the things that were of great importance to them.

Example of a Commemorative Text The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln was a speech to commemorate the lives lost during the Civil War and to reaffirm the principles of liberty and equality.

20. To Plead

Common Text Genres: Petitions, Open Letters, Advocacy Articles, Speeches.

When authors write to plead, they aim to make an urgent appeal or request for something. This could be a plea for action, support, change, etc. These texts commonly ask for social change or a change in perspective from the reader. The author may be pleading for themselves and their family (e.g. a refugee who pleads their case in a newspaper op-ed) or for the less advantaged (e.g. an activist pleading for people to donate to children in poverty).

Example of a Text that Pleads a Case In “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. pleads for an end to racial segregation and appeals for justice and equality.

21. To Celebrate

Common Text Genres: Commendatory Speeches, Reviews, Praises, Tributes.

Authors who write to celebrate aim to acknowledge, praise, or express gratitude for someone or something. They might celebrate a person, a culture, a historical event, an achievement, or a simple joy of life. A celebratory text, for example, might be a speech someone gives at a graduation ceremony, with the intention of celebrating the graduates’ successes in finally completing their degree.

Example of a Celebratory Text Maya Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise” celebrates the resilience and strength of African American women.

See Also: Examples of Text Types

Texts are written for a range of reasons. By determining the intentions of the author, we can begin to infer genre expectations, whether there will be much bias, or indeed, whether we can simply read for entertainment and throw caution to the wind! Similarly, if you want to be a writer, it’s worth examining other author’s texts that have similar purposes, and take notes on their style and turns-of-phrase to learn from them.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Understanding Your Purpose

The first question for any writer should be, "Why am I writing?" "What is my goal or my purpose for writing?" For many writing contexts, your immediate purpose may be to complete an assignment or get a good grade. But the long-range purpose of writing is to communicate to a particular audience. In order to communicate successfully to your audience, understanding your purpose for writing will make you a better writer.

A Definition of Purpose

Purpose is the reason why you are writing . You may write a grocery list in order to remember what you need to buy. You may write a laboratory report in order to carefully describe a chemistry experiment. You may write an argumentative essay in order to persuade someone to change the parking rules on campus. You may write a letter to a friend to express your excitement about her new job.

Notice that selecting the form for your writing (list, report, essay, letter) is one of your choices that helps you achieve your purpose. You also have choices about style, organization, kinds of evidence that help you achieve your purpose

Focusing on your purpose as you begin writing helps you know what form to choose, how to focus and organize your writing, what kinds of evidence to cite, how formal or informal your style should be, and how much you should write.

Types of Purpose

Don Zimmerman, Journalism and Technical Communication Department I look at most scientific and technical writing as being either informational or instructional in purpose. A third category is documentation for legal purposes. Most writing can be organized in one of these three ways. For example, an informational purpose is frequently used to make decisions. Memos, in most circles, carry key information.

When we communicate with other people, we are usually guided by some purpose, goal, or aim. We may want to express our feelings. We may want simply to explore an idea or perhaps entertain or amuse our listeners or readers. We may wish to inform people or explain an idea. We may wish to argue for or against an idea in order to persuade others to believe or act in a certain way. We make special kinds of arguments when we are evaluating or problem solving . Finally, we may wish to mediate or negotiate a solution in a tense or difficult situation.

Remember, however, that often writers combine purposes in a single piece of writing. Thus, we may, in a business report, begin by informing readers of the economic facts before we try to persuade them to take a certain course of action.

In expressive writing, the writer's purpose or goal is to put thoughts and feelings on the page. Expressive writing is personal writing. We are often just writing for ourselves or for close friends. Usually, expressive writing is informal, not intended for outside readers. Journal writing, for example, is usually expressive writing.

However, we may write expressively for other readers when we write poetry (although not all poetry is expressive writing). We may write expressively in a letter, or we may include some expressive sentences in a formal essay intended for other readers.

Entertaining

As a purpose or goal of writing, entertaining is often used with some other purpose--to explain, argue, or inform in a humorous way. Sometimes, however, entertaining others with humor is our main goal. Entertaining may take the form of a brief joke, a newspaper column, a television script or an Internet home page tidbit, but its goal is to relax our reader and share some story of human foibles or surprising actions.

Writing to inform is one of the most common purposes for writing. Most journalistic writing fits this purpose. A journalist uncovers the facts about some incident and then reports those facts, as objectively as possible, to his or her readers. Of course, some bias or point-of-view is always present, but the purpose of informational or reportorial writing is to convey information as accurately and objectively as possible. Other examples of writing to inform include laboratory reports, economic reports, and business reports.

Writing to explain, or expository writing, is the most common of the writing purposes. The writer's purpose is to gather facts and information, combine them with his or her own knowledge and experience, and clarify for some audience who or what something is , how it happened or should happen, and/or why something happened .

Explaining the whos, whats, hows, whys, and wherefores requires that the writer analyze the subject (divide it into its important parts) and show the relationship of those parts. Thus, writing to explain relies heavily on definition, process analysis, cause/effect analysis, and synthesis.

Explaining versus Informing : So how does explaining differ from informing? Explaining goes one step beyond informing or reporting. A reporter merely reports what his or her sources say or the data indicate. An expository writer adds his or her particular understanding, interpretation, or thesis to that information. An expository writer says this is the best or most accurate definition of literacy, or the right way to make lasagne, or the most relevant causes of an accident.

An arguing essay attempts to convince its audience to believe or act in a certain way. Written arguments have several key features:

- A debatable claim or thesis . The issue must have some reasonable arguments on both (or several) sides.

- A focus on one or more of the four types of claims : Claim of fact , claim of cause and effect , claim of value , and/or claim of policy (problem solving).

- A fair representation of opposing arguments combined with arguments against the opposition and for the overall claim.

- An argument based on evidence presented in a reasonable tone . Although appeals to character and to emotion may be used, the primary appeal should be to the reader's logic and reason.

Although the terms argument and persuasion are often used interchangeably, the terms do have slightly different meanings. Argument is a special kind of persuasion that follows certain ground rules. Those rules are that opposing positions will be presented accurately and fairly, and that appeals to logic and reason will be the primary means of persuasion. Persuasive writing may, if it wishes, ignore those rules and try any strategy that might work. Advertisements are a good example of persuasive writing. They usually don't fairly represent the competing product, and they appeal to image, to emotion, to character, or to anything except logic and the facts--unless those facts are in the product's favor.

Writing to evaluate a person, product, thing, or policy is a frequent purpose for writing. An evaluation is really a specific kind of argument: it argues for the merits of the subject and presents evidence to support the claim. A claim of value --the thesis in an evaluation--must be supported by criteria (the appropriate standards of judgment) and supporting evidence (the facts, statistics, examples, or testimonials).

Writers often use a three-column log to set up criteria for their subject, collect relevant evidence, and reach judgments that support an overall claim of value. Writing a three-column log is an excellent way to organize an evaluative essay. First, think about your possible criteria. Remember: criteria are the standards of judgment (the ideal case) against which you will measure your particular subject. Choose criteria which your readers will find valid, fair, and appropriate . Then, collect evidence for each of your selected criteria. Consider the following example of a restaurant evaluation:

Overall claim of value : This Chinese restaurant provides a high quality dining experience.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is a special kind of arguing essay: the writer's purpose is to persuade his audience to adopt a solution to a particular problem. Often called "policy" essays because they recommend the readers adopt a policy to resolve a problem, problem-solving essays have two main components: a description of a serious problem and an argument for specific recommendations that will solve the problem .

The thesis of a problem-solving essay becomes a claim of policy : If the audience follows the suggested recommendations, the problem will be reduced or eliminated. The essay must support the policy claim by persuading readers that the recommendations are feasible, cost-effective, efficient, relevant to the situation, and better than other possible alternative solutions.

Traditional argument , like a debate, is confrontational. The argument often becomes a kind of "war" in which the writer attempts to "defeat" the arguments of the opposition.

Non-traditional kinds of argument use a variety of strategies to reduce the confrontation and threat in order to open up the debate.

- Mediated argument follows a plan used successfully in labor negotiations to bring opposing parties to agreement. The writer of a mediated argument provides a middle position that helps negotiate the differences of the opposing positions.

- Rogerian argumen t also wishes to reduce confrontation by encouraging mutual understanding and working toward common ground and a compromise solution.

- Feminist argument tries to avoid the patriarchal conventions in traditional argument by emphasizing personal communication, exploration, and true understanding.

Combining Purposes

Often, writers use multiple purposes in a single piece of writing. An essay about illiteracy in America may begin by expressing your feelings on the topic. Then it may report the current facts about illiteracy. Finally, it may argue for a solution that might correct some of the social conditions that cause illiteracy. The ultimate purpose of the paper is to argue for the solution, but the writer uses these other purposes along the way.

Similarly, a scientific paper about gene therapy may begin by reporting the current state of gene therapy research. It may then explain how a gene therapy works in a medical situation. Finally, it may argue that we need to increase funding for primary research into gene therapy.

Purposes and Strategies

A purpose is the aim or goal of the writer or the written product; a strategy is a means of achieving that purpose. For example, our purpose may be to explain something, but we may use definitions, examples, descriptions, and analysis in order to make our explanation clearer. A variety of strategies are available for writers to help them find ways to achieve their purpose(s).

Writers often use definition for key terms of ideas in their essays. A formal definition , the basis of most dictionary definitions, has three parts: the term to be defined, the class to which the term belongs, and the features that distinguish this term from other terms in the class.

Look at your own topic. Would definition help you analyze and explain your subject?

Illustration and Example

Examples and illustrations are a basic kind of evidence and support in expository and argumentative writing.

In her essay about anorexia nervosa, student writer Nancie Brosseau uses several examples to develop a paragraph:

Another problem, lying, occurred most often when my parents tried to force me to eat. Because I was at the gym until around eight o'clock every night, I told my mother not to save me dinner. I would come home and make a sandwich and feed it to my dog. I lied to my parents every day about eating lunch at school. For example, I would bring a sack lunch and sell it to someone and use the money to buy diet pills. I always told my parents that I ate my own lunch.

Look at your own topic. What examples and illustrations would help explain your subject?

Classification

Classification is a form of analyzing a subject into types. We might classify automobiles by types: Trucks, Sport Utilities, Sedans, Sport Cars. We can (and do) classify college classes by type: Science, Social Science, Humanities, Business, Agriculture, etc.

Look at your own topic. Would classification help you analyze and explain your subject?

Comparison and Contrast

Comparison and contrast can be used to organize an essay. Consider whether either of the following two outlines would help you organize your comparison essay.

Block Comparison of A and B

- Intro and Thesis

- Description of A

- Description of B (and how B is similar to/different from A)

Alternating Comparison of A and B

- Aspect One: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Two: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Three: Comparison/contrast of A and B

Look at your own topic. Would comparison/contrast help you organize and explain your subject?

Analysis is simply dividing some whole into its parts. A library has distinct parts: stacks, electronic catalog, reserve desk, government documents section, interlibrary loan desk, etc. If you are writing about a library, you may need to know all the parts that exist in that library.

Look at your own topic. Would analysis of the parts help you understand and explain your subject?

Description

Although we usually think of description as visual, we may also use other senses--hearing, touch, feeling, smell-- in our attempt to describe something for our readers.

Notice how student writer Stephen White uses multiple senses to describe Anasazi Indian ruins at Mesa Verde:

I awoke this morning with a sense of unexplainable anticipation gnawing away at the back of my mind, that this chilly, leaden day at Mesa Verde would bring something new . . . . They are a haunting sight, these broken houses, clustered together down in the gloom of the canyon. The silence is broken only by the rush of the wind in the trees and the trickling of a tiny stream of melting snow springing from ledge to ledge. This small, abandoned village of tiny houses seems almost as the Indians left it, reduced by the passage of nearly a thousand years to piles of rubble through which protrude broken red adobe walls surrounding ghostly jet black openings, undisturbed by modern man.

Look at your own topic. Would description help you explain your subject?

Process Analysis

Process analysis is analyzing the chronological steps in any operation. A recipe contains process analysis. First, sift the flour. Next, mix the eggs, milk, and oil. Then fold in the flour with the eggs, milk and oil. Then add baking soda, salt and spices. Finally, pour the pancake batter onto the griddle.

Look at your own topic. Would process analysis help you analyze and explain your subject?

Narration is possibly the most effective strategy essay writers can use. Readers are quickly caught up in reading any story, no matter how short it is. Writers of exposition and argument should consider where a short narrative might enliven their essay. Typically, this narrative can relate some of your own experiences with the subject of your essay. Look at your own topic. Where might a short narrative help you explain your subject?

Cause/Effect Analysis

In cause and effect analysis, you map out possible causes and effects. Two patterns for doing cause/effect analysis are as follows:

Several causes leading to single effect: Cause 1 + Cause 2 + Cause 3 . . . => Effect

One cause leading to multiple effects: Cause => Effect 1 + Effect 2 + Effect 3 ...

Look at your own topic. Would cause/effect analysis help you understand and explain your subject?

How Audience and Focus Affect Purpose

All readers have expectations. They assume what they read will meet their expectations. As a writer, your job is to make sure those expectations are met, while at the same time, fulfilling the purpose of your writing.

Once you have determined what type of purpose best conveys your motivations, you will then need to examine how this will affect your readers. Perhaps you are explaining your topic when you really should be convincing readers to see your point. Writers and readers may approach a topic with conflicting purposes. Your job, as a writer, is to make sure both are being met.

Purpose and Audience

Often your audience will help you determine your purpose. The beliefs they hold will tell you whether or not they agree with what you have to say. Suppose, for example, you are writing to persuade readers against Internet censorship. Your purpose will differ depending on the audience who will read your writing.

Audience One: Internet Users

If your audience is computer users who surf the net daily, you could appear foolish trying to persuade them to react against Internet censorship. It's likely they are already against such a movement. Instead, they might expect more information on the topic.

Audience Two: Parents

If your audience is parents who don't want their small children surfing the net, you'll need to convince them that censorship is not the solution to the problem. You should persuade this audience to consider other options.

Purpose and Focus

Your focus (otherwise known as thesis, claim, main idea, or problem statement) is a reflection of your purpose. If these two do not agree, you will not accomplish what you set out to do. Consider the following examples below:

Focus One: Informing

Suppose your purpose is to inform readers about relationships between Type A personalities and heart attacks. Your focus could then be: Type A personalities do not have an abnormally high risk of suffering heart attacks.

Focus Two: Persuading