- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Problem Solving

Problem solving, a fundamental cognitive process deeply rooted in psychology, plays a pivotal role in various aspects of human existence, especially within educational contexts. This article delves into the nature of problem solving, exploring its theoretical underpinnings, the cognitive and psychological processes that underlie it, and the application of problem-solving skills within educational settings and the broader real world. With a focus on both theory and practice, this article underscores the significance of cultivating problem-solving abilities as a cornerstone of cognitive development and innovation, shedding light on its applications in fields ranging from education to clinical psychology and beyond, thereby paving the way for future research and intervention in this critical domain of human cognition.

Introduction

Problem solving, a quintessential cognitive process deeply embedded in the domains of psychology and education, serves as a linchpin for human intellectual development and adaptation to the ever-evolving challenges of the world. The fundamental capacity to identify, analyze, and surmount obstacles is intrinsic to human nature and has been a subject of profound interest for psychologists, educators, and researchers alike. This article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of problem solving, investigating its theoretical foundations, cognitive intricacies, and practical applications in educational contexts. With a clear understanding of its multifaceted nature, we will elucidate the pivotal role that problem solving plays in enhancing learning, fostering creativity, and promoting cognitive growth, setting the stage for a detailed examination of its significance in both psychology and education. In the continuum of psychological research and educational practice, problem solving stands as a cornerstone, enabling individuals to navigate the complexities of their world. This article’s thesis asserts that problem solving is not merely a cognitive skill but a dynamic process with profound implications for intellectual growth and application in diverse real-world contexts.

The Nature of Problem Solving

Problem solving, within the realm of psychology, refers to the cognitive process through which individuals identify, analyze, and resolve challenges or obstacles to achieve a desired goal. It encompasses a range of mental activities, such as perception, memory, reasoning, and decision-making, aimed at devising effective solutions in the face of uncertainty or complexity.

Problem solving as a subject of inquiry has drawn from various theoretical perspectives, each offering unique insights into its nature. Among the seminal theories, Gestalt psychology has highlighted the role of insight and restructuring in problem solving, emphasizing that individuals often reorganize their mental representations to attain solutions. Information processing theories, inspired by computer models, emphasize the systematic and step-by-step nature of problem solving, likening it to information retrieval and manipulation. Furthermore, cognitive psychology has provided a comprehensive framework for understanding problem solving by examining the underlying cognitive processes involved, such as attention, memory, and decision-making. These theoretical foundations collectively offer a richer comprehension of how humans engage in and approach problem-solving tasks.

Problem solving is not a monolithic process but a series of interrelated stages that individuals progress through. These stages are integral to the overall problem-solving process, and they include:

- Problem Representation: At the outset, individuals must clearly define and represent the problem they face. This involves grasping the nature of the problem, identifying its constraints, and understanding the relationships between various elements.

- Goal Setting: Setting a clear and attainable goal is essential for effective problem solving. This step involves specifying the desired outcome or solution and establishing criteria for success.

- Solution Generation: In this stage, individuals generate potential solutions to the problem. This often involves brainstorming, creative thinking, and the exploration of different strategies to overcome the obstacles presented by the problem.

- Solution Evaluation: After generating potential solutions, individuals must evaluate these alternatives to determine their feasibility and effectiveness. This involves comparing solutions, considering potential consequences, and making choices based on the criteria established in the goal-setting phase.

These components collectively form the roadmap for navigating the terrain of problem solving and provide a structured approach to addressing challenges effectively. Understanding these stages is crucial for both researchers studying problem solving and educators aiming to foster problem-solving skills in learners.

Cognitive and Psychological Aspects of Problem Solving

Problem solving is intricately tied to a range of cognitive processes, each contributing to the effectiveness of the problem-solving endeavor.

- Perception: Perception serves as the initial gateway in problem solving. It involves the gathering and interpretation of sensory information from the environment. Effective perception allows individuals to identify relevant cues and patterns within a problem, aiding in problem representation and understanding.

- Memory: Memory is crucial in problem solving as it enables the retrieval of relevant information from past experiences, learned strategies, and knowledge. Working memory, in particular, helps individuals maintain and manipulate information while navigating through the various stages of problem solving.

- Reasoning: Reasoning encompasses logical and critical thinking processes that guide the generation and evaluation of potential solutions. Deductive and inductive reasoning, as well as analogical reasoning, play vital roles in identifying relationships and formulating hypotheses.

While problem solving is a universal cognitive function, individuals differ in their problem-solving skills due to various factors.

- Intelligence: Intelligence, as measured by IQ or related assessments, significantly influences problem-solving abilities. Higher levels of intelligence are often associated with better problem-solving performance, as individuals with greater cognitive resources can process information more efficiently and effectively.

- Creativity: Creativity is a crucial factor in problem solving, especially in situations that require innovative solutions. Creative individuals tend to approach problems with fresh perspectives, making novel connections and generating unconventional solutions.

- Expertise: Expertise in a specific domain enhances problem-solving abilities within that domain. Experts possess a wealth of knowledge and experience, allowing them to recognize patterns and solutions more readily. However, expertise can sometimes lead to domain-specific biases or difficulties in adapting to new problem types.

Despite the cognitive processes and individual differences that contribute to effective problem solving, individuals often encounter barriers that impede their progress. Recognizing and overcoming these barriers is crucial for successful problem solving.

- Functional Fixedness: Functional fixedness is a cognitive bias that limits problem solving by causing individuals to perceive objects or concepts only in their traditional or “fixed” roles. Overcoming functional fixedness requires the ability to see alternative uses and functions for objects or ideas.

- Confirmation Bias: Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that confirms preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. This bias can hinder objective evaluation of potential solutions, as individuals may favor information that aligns with their initial perspectives.

- Mental Sets: Mental sets are cognitive frameworks or problem-solving strategies that individuals habitually use. While mental sets can be helpful in certain contexts, they can also limit creativity and flexibility when faced with new problems. Recognizing and breaking out of mental sets is essential for overcoming this barrier.

Understanding these cognitive processes, individual differences, and common obstacles provides valuable insights into the intricacies of problem solving and offers a foundation for improving problem-solving skills and strategies in both educational and practical settings.

Problem Solving in Educational Settings

Problem solving holds a central position in educational psychology, as it is a fundamental skill that empowers students to navigate the complexities of the learning process and prepares them for real-world challenges. It goes beyond rote memorization and standardized testing, allowing students to apply critical thinking, creativity, and analytical skills to authentic problems. Problem-solving tasks in educational settings range from solving mathematical equations to tackling complex issues in subjects like science, history, and literature. These tasks not only bolster subject-specific knowledge but also cultivate transferable skills that extend beyond the classroom.

Problem-solving skills offer numerous advantages to both educators and students. For teachers, integrating problem-solving tasks into the curriculum allows for more engaging and dynamic instruction, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Additionally, it provides educators with insights into students’ thought processes and areas where additional support may be needed. Students, on the other hand, benefit from the development of critical thinking, analytical reasoning, and creativity. These skills are transferable to various life situations, enhancing students’ abilities to solve complex real-world problems and adapt to a rapidly changing society.

Teaching problem-solving skills is a dynamic process that requires effective pedagogical approaches. In K-12 education, educators often use methods such as the problem-based learning (PBL) approach, where students work on open-ended, real-world problems, fostering self-directed learning and collaboration. Higher education institutions, on the other hand, employ strategies like case-based learning, simulations, and design thinking to promote problem solving within specialized disciplines. Additionally, educators use scaffolding techniques to provide support and guidance as students develop their problem-solving abilities. In both K-12 and higher education, a key component is metacognition, which helps students become aware of their thought processes and adapt their problem-solving strategies as needed.

Assessing problem-solving abilities in educational settings involves a combination of formative and summative assessments. Formative assessments, including classroom discussions, peer evaluations, and self-assessments, provide ongoing feedback and opportunities for improvement. Summative assessments may include standardized tests designed to evaluate problem-solving skills within a particular subject area. Performance-based assessments, such as essays, projects, and presentations, offer a holistic view of students’ problem-solving capabilities. Rubrics and scoring guides are often used to ensure consistency in assessment, allowing educators to measure not only the correctness of answers but also the quality of the problem-solving process. The evolving field of educational technology has also introduced computer-based simulations and adaptive learning platforms, enabling precise measurement and tailored feedback on students’ problem-solving performance.

Understanding the pivotal role of problem solving in educational psychology, the diverse pedagogical strategies for teaching it, and the methods for assessing and measuring problem-solving abilities equips educators and students with the tools necessary to thrive in educational environments and beyond. Problem solving remains a cornerstone of 21st-century education, preparing students to meet the complex challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Applications and Practical Implications

Problem solving is not confined to the classroom; it extends its influence to various real-world contexts, showcasing its relevance and impact. In business, problem solving is the driving force behind product development, process improvement, and conflict resolution. For instance, companies often use problem-solving methodologies like Six Sigma to identify and rectify issues in manufacturing. In healthcare, medical professionals employ problem-solving skills to diagnose complex illnesses and devise treatment plans. Additionally, technology advancements frequently stem from creative problem solving, as engineers and developers tackle challenges in software, hardware, and systems design. Real-world problem solving transcends specific domains, as individuals in diverse fields address multifaceted issues by drawing upon their cognitive abilities and creative problem-solving strategies.

Clinical psychology recognizes the profound therapeutic potential of problem-solving techniques. Problem-solving therapy (PST) is an evidence-based approach that focuses on helping individuals develop effective strategies for coping with emotional and interpersonal challenges. PST equips individuals with the skills to define problems, set realistic goals, generate solutions, and evaluate their effectiveness. This approach has shown efficacy in treating conditions like depression, anxiety, and stress, emphasizing the role of problem-solving abilities in enhancing emotional well-being. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) incorporates problem-solving elements to help individuals challenge and modify dysfunctional thought patterns, reinforcing the importance of cognitive processes in addressing psychological distress.

Problem solving is the bedrock of innovation and creativity in various fields. Innovators and creative thinkers use problem-solving skills to identify unmet needs, devise novel solutions, and overcome obstacles. Design thinking, a problem-solving approach, is instrumental in product design, architecture, and user experience design, fostering innovative solutions grounded in human needs. Moreover, creative industries like art, literature, and music rely on problem-solving abilities to transcend conventional boundaries and produce groundbreaking works. By exploring alternative perspectives, making connections, and persistently seeking solutions, creative individuals harness problem-solving processes to ignite innovation and drive progress in all facets of human endeavor.

Understanding the practical applications of problem solving in business, healthcare, technology, and its therapeutic significance in clinical psychology, as well as its indispensable role in nurturing innovation and creativity, underscores its universal value. Problem solving is not only a cognitive skill but also a dynamic force that shapes and improves the world we inhabit, enhancing the quality of life and promoting progress and discovery.

In summary, problem solving stands as an indispensable cornerstone within the domains of psychology and education. This article has explored the multifaceted nature of problem solving, from its theoretical foundations rooted in Gestalt psychology, information processing theories, and cognitive psychology to its integral components of problem representation, goal setting, solution generation, and solution evaluation. It has delved into the cognitive processes underpinning effective problem solving, including perception, memory, and reasoning, as well as the impact of individual differences such as intelligence, creativity, and expertise. Common barriers to problem solving, including functional fixedness, confirmation bias, and mental sets, have been examined in-depth.

The significance of problem solving in educational settings was elucidated, underscoring its pivotal role in fostering critical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Pedagogical approaches and assessment methods were discussed, providing educators with insights into effective strategies for teaching and evaluating problem-solving skills in K-12 and higher education.

Furthermore, the practical implications of problem solving were demonstrated in the real world, where it serves as the driving force behind advancements in business, healthcare, and technology. In clinical psychology, problem-solving therapies offer effective interventions for emotional and psychological well-being. The symbiotic relationship between problem solving and innovation and creativity was explored, highlighting the role of this cognitive process in pushing the boundaries of human accomplishment.

As we conclude, it is evident that problem solving is not merely a skill but a dynamic process with profound implications. It enables individuals to navigate the complexities of their environment, fostering intellectual growth, adaptability, and innovation. Future research in the field of problem solving should continue to explore the intricate cognitive processes involved, individual differences that influence problem-solving abilities, and innovative teaching methods in educational settings. In practice, educators and clinicians should continue to incorporate problem-solving strategies to empower individuals with the tools necessary for success in education, personal development, and the ever-evolving challenges of the real world. Problem solving remains a steadfast ally in the pursuit of knowledge, progress, and the enhancement of human potential.

References:

- Anderson, J. R. (1995). Cognitive psychology and its implications. W. H. Freeman.

- Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press.

- Duncker, K. (1945). On problem-solving. Psychological Monographs, 58(5), i-113.

- Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1980). Analogical problem solving. Cognitive Psychology, 12(3), 306-355.

- Jonassen, D. H., & Hung, W. (2008). All problems are not equal: Implications for problem-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 2(2), 6.

- Kitchener, K. S., & King, P. M. (1981). Reflective judgment: Concepts of justification and their relation to age and education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 2(2), 89-116.

- Luchins, A. S. (1942). Mechanization in problem solving: The effect of Einstellung. Psychological Monographs, 54(6), i-95.

- Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition. W. H. Freeman.

- Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving (Vol. 104). Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination: Principles and procedures of creative problem solving (3rd ed.). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Polya, G. (1945). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method. Princeton University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Wisdom, intelligence, and creativity synthesized. Cambridge University Press.

OPINION article

The role of motivation in complex problem solving.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, United States

- 2 Trimberg Research Academy, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

Previous research on Complex Problem Solving (CPS) has primarily focused on cognitive factors as outlined below. The current paper discusses the role of motivation during CPS and argues that motivation, emotion, and cognition interact and cannot be studied in an isolated manner. Motivation is the process that determines the energization and direction of behavior ( Heckhausen, 1991 ).

Three motivation theories and their relation to CPS are examined: McClelland's achievement motivation, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and Dörner's needs as outlined in PSI-theory. We chose these three theories for several reasons. First, space forces us to be selective. Second, the three theories are among the most prominent motivational theories. Finally, they are need theories postulating several motivations and not just one. A thinking-aloud protocol is provided to illustrate the role of motivational and cognitive dynamics in CPS.

Problems are part of all the domains of human life. The field of CPS investigates problems that are complex, dynamic, and non-transparent ( Dörner, 1996 ). Complex problems consist of many interactively interrelated variables. Dynamic ones change and develop further over time, regardless of whether the involved people take action. And non-transparent problems have many aspects of the problem situation that are unclear or unknown to the involved people.

CPS researchers focus exactly on such kinds of problems. Under a narrow perspective, CPS can be defined as thinking that aims to overcome barriers and to reach goals in situations that are complex, dynamic, and non-transparent ( Frensch and Funke, 1995 ). Indeed, past research has shown the influential role of task properties ( Berry and Broadbent, 1984 ; Funke, 1985 ) and of cognitive factors on CPS strategies and performance, such as intelligence (e.g., Süß, 2001 ; Stadler et al., 2015 ), domain-specific knowledge (e.g., Wenke et al., 2005 ), cognitive biases and errors (e.g., Dörner, 1996 ; Güss et al., 2015 ), or self-reflection (e.g., Donovan et al., 2015 ).

Under a broader perspective, CPS can be defined as the study of cognitive, emotional, motivational, and social processes when people are confronted with such complex, dynamic and non-transparent problem situations ( Schoppek and Putz-Osterloh, 2003 ; Dörner and Güss, 2011 , 2013 ; Funke, 2012 ). The assumption here is that focusing solely on cognitive processes reveals an incomplete picture or an inaccurate one.

To study CPS, researchers have often used computer-simulated problem scenarios also called microworlds or virtual environments or strategy games. In these situations, participants are confronted with a complex problem simulated on the computer from which they gather information, and identify solutions. These decisions are then implemented into the system and result in changes to the problem situation.

Previous Research on Motivation and CPS

The idea to study the interaction of motivation, emotion, and cognition is not new ( Simon, 1967 ). However, in practice this has been rarely examined in the field of CPS. One study assessed the need for cognition (i.e., the tendency to engage in thinking and reflecting) and showed how high need of cognition was related to broader information collection and better performance in a management simulation ( Nair and Ramnarayan, 2000 ).

Vollmeyer and Rheinberg (1999 , 2000) explored in two studies the role of motivational factors in CPS. They assessed mastery confidence (similar to self-efficacy), incompetence fear, interest, and challenge as motivational factors. Their results demonstrated that mastery confidence and incompetence fear were good predictors for learning and for knowledge acquisition.

CPS Assessment

Before we describe three theories of motivation and how they might be related and applicable to CPS, we will briefly describe the WINFIRE computer simulation ( Gerdes et al., 1993 ; Schaub, 2009 ) and provide a part of a thinking-aloud protocol of one participant while working on WINFIRE. WINFIRE is the simulation of small cities surrounded by forests. Participants take the role of fire-fighting commanders who try to protect cities and forests from approaching fires. Participants can give a series of commands to several fire trucks and helicopters. In WINFIRE quick decisions and multitasking are required in order to avoid fires spreading. In one study, participants were also instructed to think aloud, i.e., to say aloud everything that went through their minds while working on WINFIRE. These thinking-aloud protocols, also called verbal protocols, were audiotaped and transcribed in five countries and compared (see Güss et al., 2010 ).

The following is a verbatim WINFIRE thinking-aloud protocol of a US participant ( Güss et al., 2010 ):

Ok, I don't see any fires yet. I'm trying to figure out how the helicopters pick up the water from the ponds. I put helicopters on patrol mode. Not really sure what that does. It doesn't seem to be moving. Oh, there it goes, it's moving…I guess you have to wait till there's a fire showing…Ok, fire just started in the middle, so I have to get some people to extinguish it. Ok, now I have another fire going here. I'm in trouble here. Ok. Ok, when I click extinguish, it don't seem to respond. Guess I'm not clear how to get trucks right to the fire. Ok, one fire has been extinguished, but a new one started in the same area. I'm getting more trucks out there trying to figure out, how to get helicopters to the pond. I still haven't figured that out, because they have to pick up the water. Ok, got a pretty good fire going here, so I'm going to put all the trucks on action, ok, water thing is making me mad. Ok. I'm not sure how it goes? Ok, the forest is burning up now—extinguish! Ok, ok, I'm in big trouble here…

Psychological Theories of Motivation and their Application to CPS

Mcclelland's human motivation theory.

In his Human Motivation theory, McClelland distinguishes three needs (power, affiliation, and achievement) and argues that human motivation is a response to changes in affective states. A specific situation will cause a change in the affective state through the non-specific response of the autonomic nervous system. This response will motivate a person toward a goal to reach a different affective state ( McClelland et al., 1953 ). An affective state may either be positive or negative, determining the direction of motivated behavior as either approach oriented, i.e., to maintain the state, or avoidance oriented, i.e., to avoid or discontinue the state ( McClelland et al., 1953 ).

Motivation intensity varies among individuals based on perception of the stimulus and the adaptive abilities of the individual. Hence, when a discrepancy exists between expectation and perception, then a person will be motivated to eliminate this discrepancy ( McClelland et al., 1953 ). In the statement from the thinking-aloud protocol we can infer the participant's achievement motivation, “ Guess I'm not clear how to get trucks right to the fire. Ok, one fire has been extinguished, but a new one started in the same area.” The participant at first begins to give up and reduce effort, but then achieves a step toward the goal. This achievement causes the reevaluation of the discrepancy between ability and the goal as not too large to overcome. This realization motivates the participant to continue working through the scenario. Whereas, the need for achievement seems to guide CPS, the needs for power and affiliation cannot be observed in the current thinking-aloud protocol.

Based on the previous discussion we can derive the following predictions:

Prediction 1 : Approach-orientation will lead to greater engagement in CPS compared to avoidance-orientation.

Prediction 2 : Based on an individual's experience either power, affiliation, or achievement will become dominant and guide the strategic approach in CPS.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs ( Maslow, 1943 , 1954 ) suggests that everyone has five basic needs that act as motivating forces in a person's life. Maslow's hierarchy takes the form of a pyramid in which needs lower in the pyramid are primary motivators. They have to be met before higher needs can become motivating forces. At the bottom of the pyramid are the most basic needs beginning with physiological needs, such as hunger, and followed by safety needs. Then follow the psychological needs of belongingness and love, and then esteem. Once these four groups of needs have been met, a person may reach the self-fulfillment stage of self-actualization at which time a person can be motivated to achieve ones full potential ( Maslow, 1943 ).

The first four groups of needs are external motivators because they motivate through both deficiency and fulfillment. In essence, a person fulfills a need which then releases the next unsatisfied need to be the dominant motivator ( Maslow, 1943 , 1954 ). The safety need is often understood as seeking shelter, but Maslow also understands safety also as wanting “a predictable, orderly world” ( Maslow, 1943 , p. 377), “an organized world rather than an unorganized or unstructured one” ( Maslow, 1943 , p. 377). Safety refers to the “common preference for familiar rather than unfamiliar things” ( Maslow, 1943 , p. 379).

In this sense the safety need becomes active when the person does not understand what is happening in the microworld, as the following passage of the thinking-aloud protocol illustrates. “ I put helicopters on patrol mode. Not really sure what that does. It doesn't seem to be moving.” The safety need is demonstrated in the person's desire for organization, since unknown and unexpected events are seen as threats to safety.

The esteem need as a motivator becomes evident through the statement, “ Guess I'm not clear how to get trucks right to the fire.” The participant becomes aware of his inability to control the situation which affects his self-esteem. The esteem need is never fulfilled in the described situation and remains the primary motivator. The following statements show how affected the participant's esteem need is by the inability to control the burning fires. “ Ok. I'm not sure how it goes? Ok, the forest is burning up now—extinguish! Ok, ok, I'm in big trouble .”

Prediction 3 : A strong safety need will be related to elaborate and detailed information collection in CPS compared to low safety need.

Prediction 4 : People with high esteem needs will be affected more by difficulties in CPS and engage more often in behaviors to protect their esteem compared to people with low esteem needs.

Dörner's Theory of Motivation as Part of PSI-Theory

PSI-theory described the interaction of cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes ( Dörner, 2003 ; Dörner and Güss, 2011 ). Only a small part of the theory is examined here. Briefly, the theory encompasses five basic human needs: the existential needs (thirst, hunger, and pain avoidance), the sexuality need, and the social need for affiliation (group binding), the need for certainty (predictability), and the need for competence (mastery). If the environment is unpredictable, the certainty need becomes active. If we are not able to cope with problems, the competence need becomes active. The need for competence also becomes active when any other need becomes activated. With an increase in needs, the arousal increases.

The first three needs cannot be observed or inferred from the thinking-aloud protocol provided. Statements like, “I'm trying to figure out how the helicopters pick up the water from the ponds.” and “Guess I'm not clear how to get trucks right to the fire,” demonstrate the needs for certainty and competence, i.e., to make the environment predictable and controllable.

The following statements reflect the participant's need for competence, i.e., the inefficacy or incapability of coping with problems. “ I'm in trouble here…ok, water thing is making me mad .” Not being able to extinguish the fires that are approaching cities and are destroying forests is experienced as anger. The arousal rises as the resolution level of thinking decreases. So, the participant does not think about different options in an elaborate manner. Yet, the participant becomes aware of his failure. The competence need then causes the participant to search for possible solutions, “ I still haven't figured that out because they have to pick up the water…” The need for competence is satisfied when the problem solver is able to change either the environment or ones views of the environment.

Prediction 5 : A strong certainty need is positively related to a strong competence need.

Prediction 6 : High need for certainty paired with high need for competence can lead to safeguarding behavior, i.e., background monitoring.

Prediction 7 : An increase in the competence and uncertainty needs leads to increased arousal and a lower resolution level of thinking. CPS becomes one-dimensional and possible long-term and side-effects are not considered adequately.

Summary and Evaluation

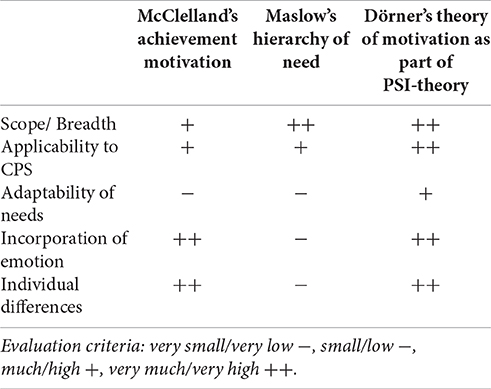

We have briefly discussed three motivation theories and their relation to CPS referring to one thinking-aloud protocol: McClelland's achievement motivation, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and Dörner's needs as outlined in PSI-theory.

A Comparison of Three Need Theories in the Context of CPS.

Comparing the scope of the three theories and referring to the scope and different needs covered in the three theories, McClelland's theory describes three needs (power, affiliation, and achievement), Maslow's theory describes five groups of needs (physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, self-actualization), and Dörner's theory describes five different needs (existential, sexuality, affiliation, certainty, and competence).

All three theories can be applied to CPS. McClelland's need for achievement, Maslow's needs for esteem and safety, and Dörner's needs for certainty and competence could be inferred from the thinking–aloud passage. The need for affiliation which is a part of each of the three theories could play an important role when groups solve complex problems.

The existential needs and the need for affiliation outlined in PSI-theory can also be found in Maslow's hierarchy of needs. These two theories differ in the adaptability of the needs. However, Maslow's esteem needs are only activated as the primary motivator as the physiological needs, belongingness, and love needs are met. The needs are more fluidly described as motivators in PSI-theory. One need becomes the dominant motive according to the expectancy–value principle. Expectancy stands for the estimated likelihood of success. The value of a motive stands for the strength of the need. According to McClelland's theory, the role of three motivations develops through life experience in a specific culture; and often times, one of the three becomes the main driving force for a person, almost like a personality trait. In that sense, there is not much flexibility.

Motivation and emotion are closely related as became partially clear in the discussion of McClelland's theory. Emotions are discussed in detail in PSI-theory, but space does not allow us to discuss those in detail here (see Dörner, 2003 ). Emotions are not described in detail in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

Individual differences in motivation and needs are discussed in two of the three theories. According to McClelland, a person develops an individual achievement motive by learning one's own abilities from past achievements and failures. Based on different learning histories, different persons will have a different dominant motivation guiding behavior in a given situation. Learning history also influences the competence need in PSI-theory. Additionally PSI-theory assumes individual differences that are simulated through different individual motivational parameters in the theory. The certainty need, for example, becomes active when there is a deviation from a given set point. Individual differences are related to different set points and how sensitive the deviations are (e.g., deviation starts quickly vs. deviation starts slowly).

The thinking-aloud example from the WINFIRE microworld described earlier demonstrates that a person's CPS process is influenced by the person's needs. We have focused in our discussion on motivational processes that are considered in the framework of need theories. Beyond that, other motivational theories exist that focus on the importance of motivation for learning and achievement (e.g., expectancy, reasons for engagement, see Eccles and Wigfield, 2002 ). Thus, the applicability of these theories to CPS could be explored in future studies as well.

We discussed the three motivational theories of McClelland's Achievement Motivation, Maslow's Hierarchy of Need, and Dörner's Theory of Motivation as part of PSI-Theory. Although, the theories differ our discussion has shown that the three theories can be applied to CPS. Problem solving is a motivated process and determined by human motivations and needs.

Author Contributions

The first author CG conceptualized the manuscript, selected the thinking-aloud passage, the second author MB primarily summarized McClellands and Maslow's theories. All authors contributed to writing up the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Berry, D. C., and Broadbent, D. E. (1984). On the relationship between task performance and associated verbalizable knowledge. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 36A, 209–231. doi: 10.1080/14640748408402156

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Donovan, S., Güss, C. D., and Naslund, D. (2015). Improving dynamic decision making through training and self-reflection. Judgm. Decis. Making 10, 284–295.

Google Scholar

Dörner, D. (1996). The logic of failure. Recognizing and Avoiding Error in Complex Situations . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Dörner, D. (2003). Bauplan für eine Seele [Blueprint for a soul] . Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Dörner, D., and Güss, C. D. (2011). A psychological analysis of Adolf Hitler's decision making as Commander in Chief: summa confidentia et nimius metus. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 15, 37–49. doi: 10.1037/a0022375

Dörner, D., and Güss, C. D. (2013). PSI: a computational architecture of cognition, motivation, and emotion. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 17, 297–317. doi: 10.1037/a0032947

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurevsych.53.100901.135153

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Frensch, P., and Funke, J. (eds.) (1995). Complex Problem Solving: The European Perspective . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Funke, J. (1985). Steuerung dynamischer Systeme durch Aufbau und Anwendung subjektiver Kausalmodelle [Control of dynamic systems via Construction and Application of subjective causal models]. Zeitschrift für Psychol. 193, 443–465.

Funke, J. (2012). “Complex problem solving,” in Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning , ed N. M. Seel (Heidelberg: Springer), 682–685.

Gerdes, J., Dörner, D., and Pfeiffer, E. (1993). Interaktive Computersimulation “Winfire.” [The Interactive Computer Simulation “Winfire”] . Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg: Lehrstuhl Psychologie, II.

Güss, C. D., Tuason, M. T., and Gerhard, C. (2010). Cross-national comparisons of complex problem-solving strategies in two microworlds. Cogn. Sci. 34, 489–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2009.01087.x

Güss, C. D., Tuason, M. T., and Orduña, L. V. (2015). Strategies, tactics, and errors in dynamic decision making. J. Dyn. Decis. Making 1, 1–14. doi: 10.11588/jddm.2015.1.13131

CrossRef Full Text

Heckhausen, H. (1991). Motivation and Action . New York, NY: Springer.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and Personality . New York, NY: Harper and Row.

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., and Lowell, E. L. (1953). The Achievement Motive . East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Nair, K. U., and Ramnarayan, S. (2000). Individual differences in need for cognition and complex problem solving. J. Res. Pers. 34, 305–328. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.1999.2274

Schaub, H. (2009). Fire Simulation . Ottobrunn: IABG.

Schoppek, W., and Putz-Osterloh, W. (2003). Individuelle Unterschiede und die Bearbeitung komplexer Probleme. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychol. 24, 163–173. doi: 10.1024/0170-1789.24.3.163

Simon, H. A. (1967). Motivational and emotional controls of cognition. Psychol. Rev. 74, 29–39. doi: 10.1037/h0024127

Süß, H.-M. (2001). “Die Rolle von Intelligenz und Wissen für erfolgreiches Handeln in komplexen Problemsituationen [The role of intelligence and knowledge for successful performance in complex problem solving],” in Komplexität und Kompetenz: Ausgewählte Fragen der Kompetenzforschung , ed G. Franke (Bielefeld: Bertelsmann), 249–275.

Stadler, M., Becker, N., Gödker, M., Leutner, D., and Greiff, S. (2015). Complex problem solving and intelligence: a meta-analysis. Intelligence 53, 92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2015.09.005

Vollmeyer, R., and Rheinberg, F. (1999). Motivation and metacognition when learning a complex system. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 14, 541–554. doi: 10.1007/BF03172978

Vollmeyer, R., and Rheinberg, F. (2000). Does motivation affect performance via persistence? Learn. Instruct. 10, 293–309. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(99)00031-6

Wenke, D., Frensch, P. A., and Funke, J. (2005). “Complex problem solving and intelligence: empirical relation and causal direction,” in Cognition and Intelligence: Identifying the Mechanisms of the Mind , eds R. J. Sternberg and J. E. Pretz (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 160–187.

Keywords: complex problem solving, dynamic decision making, simulation, motivation, PSI-theory, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, achievement motivation

Citation: Güss CD, Burger ML and Dörner D (2017) The Role of Motivation in Complex Problem Solving. Front. Psychol . 8:851. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00851

Received: 16 March 2017; Accepted: 09 May 2017; Published: 23 May 2017.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2017 Güss, Burger and Dörner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: C. Dominik Güss, ZGd1ZXNzQHVuZi5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

COMMENTS

Nov 12, 2021 · Learning motivation is usually considered to be conducive to problem solving as it influences the initiation, direction, and intensity of cognitive processing (Baars et al., Citation 2017). The motivation to deal with problem-solving tasks can come from the learners themselves or be triggered by task design.

Understanding these stages is crucial for both researchers studying problem solving and educators aiming to foster problem-solving skills in learners. Cognitive and Psychological Aspects of Problem Solving. Problem solving is intricately tied to a range of cognitive processes, each contributing to the effectiveness of the problem-solving endeavor.

Problem-Solving Skills," and one (1) or 5.88% of the student were classified with "Very High Problem-Solving Skills." The students exposed to non-GAI have an MPS of 63.24%,

May 22, 2017 · The Role of Motivation in Complex Problem Solving Previous research on Complex Problem Solving (CPS) has primarily focused on cognitive factors as outlined below. The current paper discusses the role of motivation during CPS and argues that motivation, emotion, and cognition interact and cannot be studied in an isolated manner.

students can foster problem-solving, metacognitive skills and motivation. 3. Theoretical underpinnings of PBL Some of the following key points are here for PBL learners 1). Students should have some background knowledge, assumptions and experiences. 2). Learning happens in collaborative setting in social context. 3).

Jun 5, 2012 · Classical theories of problem solving have emphasized the role of discovery or illumination as a primary motive to learn, but contemporary research has uncovered an array of highly predictive task- and performance-related motivational beliefs, such as self-efficacy, outcome expectations, intrinsic task interest, and learning goal orientations.