- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Forums Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Presentations

How to Conduct a Group Discussion

Last Updated: November 2, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Trudi Griffin, LPC, MS . Trudi Griffin is a Licensed Professional Counselor based in Wisconsin. She specializes in addictions, mental health problems, and trauma recovery. She has worked as a counselor in both community health settings and private practice. She also works as a writer and researcher, with education, experience, and compassion for people informing her research and writing subjects. She received Bachelor’s degrees in Communications and Psychology from the University of Wisconsin, Green Bay. She also earned an MS in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Marquette University. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 193,490 times.

There will likely be times in your life when you will be working in a group, possibly many times. You may have to lead a discussion as part of a school assignment or you may be responsible for leading a discussion in a work setting. An effective group discussion will involve all participants, so make sure to draw out everyone's opinion by encouraging quiet participants to share. It is equally important that you value each member's opinion and all contributions by capturing what is communicated on paper as you go. Welcome new topics as they come up but be sure to direct the discussion toward some kind of conclusion. With a little knowhow and by being perceptive and proactive you can lead a great group discussion.

Beginning the Discussion

- You can go around the room and have everyone say their name. You may want each person to explain why they're participating in the discussion.

- For a classroom setting, an icebreaker activity may work well. You could, for example, have everyone share their favorite ice cream flavor.

- Advise everyone to treat one another with respect. Make it clear there should be no name-calling, personal attacks, or profanity. You can argue with someone's idea or opinion, but cannot argue with that person on a personal level.

- Make sure people know not to interrupt. Remind everyone the point of this discussion is for everyone to share equally.

- Remind everyone to be aware of time, and to make their points succinctly so everyone has the chance to share.

- Encourage people to consider their comments seriously, and to avoid becoming defensive if someone disagrees.

- You can introduce the topic by asking questions. For example, say something like, "Why are we all here?" This can be helpful if you're managing a conflict, or making plans for an event that are uncertain.

- You can also quickly introduce the idea. Say something like, "As you know, today in class we're going to discuss gun control."

- Your questions should encourage people to share meaningful thoughts and ideas. Questions can be confusing to the participants. Many participants may not know the answers right away themselves, encouraging them to think during discussion.

- For example, "What is it about our culture that contributes to gun violence? What are ways we can reduce the problem?" These questions are complicated, and have many potential answers.

Facilitating an Open Conversation

- You want to make sure the discussion does not stay too long on one topic, so if you're lingering on one talking point, see what new ideas are being generated. When you hear a new potential idea, you can encourage the group to discuss this.

- For example, one student brings up the second amendment during the gun control debate. You have yet to really discuss the history and implications of that amendment. You can say something like, "Hey, I think Bryce made a great point. What about the second amendment? How does that affect our relationship with guns in the United States?"

- Follow up questions should usually be vague. For example, you can say something like, "Really? What makes you think that?" You can also say, "How do you feel about that fact?"

- Watch your tone. You want to sound friendly and inquisitive rather than authoritarian. If delivered in a harsh tone, "What makes you think that?" can sound like you disagree. When delivered in a light tone, you simply come off like you're curious to find new information.

- Breaking up into small groups for a moment can encourage more participation. You can tell the group to discuss the issue with the person next to them for 5 minutes. Then, you can re-assemble and ask everyone to share the discussions they had.

- You should also make it clear that everyone's opinion matters. Write everyone's comment on a white board. Encourage students to build on other people's comments. If a participant made a good point awhile ago, but has been silent for a bit, return to his or her point to move the discussion forward.

- Keep asking questions throughout the discussion. In addition to asking participants a question, ask questions of the group that complicate the issue.

- For example, "While we all disagree on what the second amendment means, how much does that matter? Culturally, people interpret it in a specific way. Does the cultural interpretation matter more than the literal meaning?"

- Push participants for clarification. Getting more insight out of an opinion can help introduce new ideas, leading to new insight for the discussion. For example, "I understand you feel banning automatic weapons would decrease gun violence, but can you tell me more about what makes you feel that way?"

- Make sure everyone understands the key points made. You can say something like, "I'm hearing half of you feel that we have the right to own guns for protection, while half of you feel there should be heavier restrictions."

- Have the group review the discussion from here. Ask open ended questions that will lead the group to reflect on what everyone learned. For example, "Have your opinions on gun control changed? Leaving this classroom, how do you think you'll discuss the issue in the future?"

Handling Problems

- If one group has been bringing up the same point for awhile, try to cut it off in a respectful manner. For example, "I think those issues are important, but I want to make sure we give time to other factors surrounding this debate."

- Try to bring the discussion back to the shy people. For example, "Lucy made up an interesting point earlier. Maybe we could revisit that."

- Try asking the talkative person to act as an observer for a few minutes. For example, "John, you seem to have strong opinions. Why don't you just observe for a few minutes. Take notes on the discussion. You can share these later, and we can see how the discussion shaped your opinions."

- You can also try to use the dominant person's input to steer the conversation in a new direction. For example, "John has brought up conceal and carry laws several times, and seems quite passionate about this. Let's talk for a bit about why people feel strongly about such laws."

- Ask people arguing to back up their opinions using outside authority. This will cause the discussion to become more objective and less personal.

- Ask people to be aware of differences in values. Say something like, "I feel like the two of you share different values. Can we talk about that?"

- You can also list both sides of the argument on the board. Encourage participants to continue to debate the point, but in a respectful manner. Say something like, "I think we should talk about this, as we all feel strongly, but let's take turns examining each other's points respectfully."

- You can ask the shy participant directly. For example, "Molly, why don't you tell us how you feel?"

- You can also have everyone write down their answers to a question and then share. A nervous participant may feel more comfortable sharing if they have their idea written down.

How Can You Conduct an Effective Workshop or Discussion?

Expert Q&A

- Respect everyone's ideas and opinions. Even if you personally disagree, your job is to lead the discussion and not participate yourself. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://sheridan.brown.edu/resources/classroom-practices/discussions-seminars/facilitating-effective-group-discussions

- ↑ https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/leadership/group-facilitation/group-discussions/main

- ↑ https://teaching.cornell.edu/using-effective-questions

- ↑ https://www.nhi.fhwa.dot.gov/LearnersFirst/group-discussions.htm

- ↑ https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/implementing-group-work-classroom

- ↑ https://tltc.umd.edu/instructors/teaching-resources/discussions

About This Article

To conduct a group discussion, start by having everyone introduce themselves. Next, establish some ground rules, like treating everyone with respect, no interrupting, and being succinct. Then, explain the topic that’s up for discussion and ask an open-ended question to begin the conversation. As you facilitate the conversation, you may want to interject to point out particularly good points or redirect the dialogue if it’s going too far off track. You can also ask follow-up questions to help participants think more deeply about their claims. To learn how to encourage everyone to participate, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Shirley Chen

May 3, 2020

Did this article help you?

Sourish Das

Nov 21, 2016

Verma Ashish

Mar 4, 2017

Sudhir Dabke

Jul 29, 2016

Mohith R. S.

Jun 13, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Center for Teaching Innovation

Ideas for group and collaborative assignments, why collaborative learning.

Collaborative learning can help

- students develop higher-level thinking, communication, self-management, and leadership skills

- explore a broad range of perspectives and provide opportunities for student voices/expression

- promote teamwork skills & ethics

- prepare students for real life social and employment situations

- increase student retention, self-esteem, and responsibility

Collaborative activities & tools

Group brainstorming & investigation in shared documents.

Have students work together to investigate or brainstorm a question in a shared document (e.g., structured Google doc, Google slide, or sheet) or an online whiteboard, and report their findings back to the class.

- Immediate view of contributions

- Synchronous & asynchronous group work

- Students can come back to the shared document to revise, re-use, or add information

- Google workspace (Google Docs, Sheets, Forms, & Slides)

- Microsoft 365 (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Teams)

- Cornell Box (document storage)

- Whiteboarding tools ( Zoom , JamBoard , Miro , Mural , etc.)

Considerations

- Sharing settings

- Global access

- Accessibility

Group discussions with video conferencing and chat

Ask students to post an answer to a question or share their thoughts about class content in the Zoom chat window (best for smaller classes). For large classes, ask students in Zoom breakout rooms to choose a group notetaker to post group discussion notes in the chat window after returning to the main class session.

You can also use a discussion board for asynchronous group work.

- Students can post their reflections in real time and read/share responses

- If group work is organized asynchronously, students can come back to the discussion board at their own time

Synchronous group work:

- Zoom Breakout rooms

- Microsoft Teams

- Canvas Conferences

- Canvas Group Discussions

- Ed Discussion

- Stable access to WiFi and its bandwidth

- Clear expectations about participation and pace for asynchronous discussion boards

- Monitoring discussion boards

Group projects: creation

Students retrieve and synthesize information by collaborating with their peers to create something new: a written piece, an infographic, a piece of code, or students collectively respond to sample test questions.

- Group projects may benefit from features offered by shared online space (ability to chat, do video conferencing, share files and links, post announcements and discussion threads, and build content)

- Canvas groups with all available tools

Setting up groups and group projects for success may require the following steps:

- Introduce group or peer work early in the semester

- Establishing ground rules for participation

- Plan for each step of group work

- Explain how groups will function and the grading

Peer learning, critiquing, giving feedback

Students submit their first draft of an essay, research proposal, or a design, and the submitted work is distributed for peer review. If students work on a project in teams, they can check in with each other through a group member evaluation activity. Students can also build on each other’s knowledge and understanding of the topic in Zoom breakout room discussions or by sharing and responding in an online discussion board.

When providing feedback and critiquing, students have to apply their knowledge, problem-solving skills, and develop feedback literacy. Students also engage more deeply with the assignment requirements and/or the rubric.

- FeedbackFruits Peer Review and Group Member Evaluation

- Canvas Peer Review

- Turnitin PeerMark

- Zoom breakout rooms

- Canvas discussions, and other discussion tools

- Peer review is a multistep activity and may require careful design and consideration of requirements to help students achieve the learning outcomes. The assignment requirements will inform which platform is best to use and the best settings for the assignment

- We advise making the first peer review activity a low-stakes assignment for the students to get used to the platform and the flow.

- A carefully written rubric helps guide students through the process of giving feedback and yields more constructive feedback.

- It helps when the timing for the activity is generous, so students have enough time to first submit their work and then give feedback.

Group reflection & social annotation activities

Students can annotate, highlight, discuss, and collaborate on text documents, images, video, audio, and websites. Instructors can post guiding questions for students to respond to, and allow students to post their own questions to be answered by peers. This is a great reading activity leading up to an inperson discussion.

- Posing discussion topics and/or questions for students to answer as they read a paper

- Students can collaboratively read and annotate synchronously and asynchronously

- Collaborative annotation helps students to acknowledge some parts of reading that they could have neglected otherwise

- Annotating in small groups

- FeedbackFruits

- Interactive Media (annotations on document, video, and audio)

- Providing students with thorough instructions

- These are all third-party tools, so the settings should be selected thoughtfully

- Accessibility (Perusall)

Group learning with polling and team competitions

Instructors can poll students while they are in breakout rooms using Poll Everywhere. This activity is great for checking understanding and peer learning activities, as students will be able to discuss solutions.

- Students can share screen in a breakout room and/or answer questions together

- This activity can be facilitated as a competition among teams

- Poll Everywhere competitions, surveys, and polls facilitated in breakout rooms

- Careful construction of questions for students

- Students may need to be taught how to answer online questions

- It requires appropriate internet connection and can experience delays in response summaries.

More information

- Group work & collaborative learning

- Collaboration tools

- Active learning

- Active learning in online teaching

Growth Tactics

Types of Group Discussion: Strategies for Effective Discussions

Jump To Section

Group discussion is a valuable tool for learning, collaboration, and fostering critical thinking skills. Whether you are a student preparing for an exam, an educator looking for ways to engage your students, or a leader trying to solve a problem, understanding the different types of group discussions, topics, and strategies is essential. In this blog post, we will explore the various types of group discussions, how to choose a suitable topic, and strategies for facilitating meaningful and productive discussions.

Understanding Group Discussion

Group discussions are a form of interactive communication that involves a small group of individuals sharing their thoughts, ideas, and opinions on a specific topic. These discussions can take place in various settings, such as classrooms, organizations, or professional settings, and can serve different purposes, such as problem-solving, decision-making, or brainstorming.

Types of Group Discussion

Group discussions offer a dynamic environment for sharing thoughts, ideas, and opinions. They can be beneficial for learning, collaboration, and developing critical thinking skills . Let’s explore three types of group discussions: case-based discussions, topic-based discussions, and structured group discussions.

1. Case-Based Discussions

In case-based discussions, participants analyze and discuss specific cases or scenarios. They evaluate possible solutions or approaches, which helps develop problem-solving and analytical skills. By actively engaging with real or hypothetical case studies, participants enhance their ability to think critically about complex situations.

2. Topic-Based Discussions

Topic-based discussions center around a specific subject or theme. Participants express their opinions, present arguments, and explore different viewpoints. These discussions improve communication skills and foster critical thinking as participants analyze and evaluate various perspectives on a given topic.

3. Structured Group Discussions

Structured group discussions follow predefined formats or rules. A moderator guides the discussion by posing questions and facilitating conversation. This format ensures active participation and constructive exchanges, providing a framework for focused and productive discussions.

By understanding the different types of group discussions, participants can choose the most suitable format for their goals and create an engaging and interactive environment for meaningful conversations.

Choosing a Suitable Topic

Selecting an appropriate topic is crucial for a successful group discussion. Consider the following factors when choosing a topic:

1. Relevance to the Participants

The topic should be relevant to the participants’ interests, experiences, or areas of study. This helps create a sense of engagement and encourages active participation.

2. Controversial and Thought-Provoking

Controversial topics or those that require critical thinking and analysis can spark lively and meaningful discussions. Avoid vague or overly simplistic topics that do not stimulate thoughtful discussion.

3. Current Affairs and Real-World Issues

Discussing current affairs and real-world issues helps participants develop an understanding of the socio-economic and political landscape. These topics encourage participants to think critically and evaluate different perspectives.

Strategies for Effective Group Discussions

To make group discussions productive and engaging, consider implementing the following strategies:

1. Establish Clear Ground Rules

Start by establishing clear guidelines and expectations for the discussion. These ground rules should emphasize the importance of active listening, respectful communication, and equal participation. By setting a foundation of mutual respect and inclusivity, you create a safe and open environment for all participants to contribute their ideas.

2. Encourage the Expression of Diverse Perspectives

Promote a culture that values and encourages diverse perspectives. Encourage participants to share their unique viewpoints, experiences, and ideas. By actively seeking and embracing different perspectives, you enrich the conversation and foster a deeper understanding of the topic at hand. Remember that diversity of thought leads to more innovative and creative solutions.

3. Foster Lateral Thinking and Problem-Solving

Encourage participants to think critically and approach problems from various angles. Foster an environment that values and promotes lateral thinking, which involves exploring unconventional or alternative solutions. Encourage participants to challenge assumptions and consider different perspectives to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

4. Provide Structured Discussion Prompts

Prepare a list of discussion prompts or questions in advance to guide the conversation. These prompts should cover various aspects of the topic and encourage participants to think critically and express their thoughts. Structured discussion prompts provide a framework and keep the conversation focused and productive. This helps ensure that all important aspects of the topic are explored.

5. Facilitate Active Participation

Actively engage all participants to facilitate their active participation in the discussion. Encourage quieter participants to contribute by directly asking for their input or by creating a supportive environment that encourages them to share their thoughts. By ensuring that everyone feels heard and valued, you create a space for meaningful and collaborative discussions.

By implementing these strategies, you can make your group discussions more effective, inclusive, and thought-provoking. These approaches promote critical thinking, enhance problem-solving skills, and allow for the exploration of multiple perspectives. Remember that an open and respectful environment is key to fostering successful group discussions.

Common Challenges in Group Discussions and How to Overcome Them

Group discussions can be an effective way to generate ideas, facilitate collaboration, and arrive at well-informed decisions. However, there are common challenges that can arise during group discussions. Here are some of these challenges and strategies to overcome them:

1. Dominant Personalities

Some participants may have dominant personalities that can overpower the conversation, making others feel unheard or overshadowed. To prevent dominance, set equal speaking opportunities for everyone. Encourage active listening to make sure everyone’s voice is heard. If someone is dominating the conversation, try direct questions to other participants and redirecting the conversation towards the quieter members.

2. Groupthink

Groupthink occurs when the desire for group harmony leads to conformity and a lack of critical thinking. To avoid it, make sure to encourage diverse opinions, ideas, and perspectives. Assign a designated devil’s advocate whose role is to challenge proposed ideas. Anonymous ideation sessions and setting the tone of every idea is welcome helps in the same.

3. Lack of Focus

Conversations may easily veer off-topic or lack a clear focus, making it difficult to achieve the intended goals. Keep the conversation focused by setting and reviewing an agenda periodically. Encourage participants to take constructive breaks that revitalize their focus. Use summarizing techniques throughout the discussion to align the focus.

4. Unequal Participation

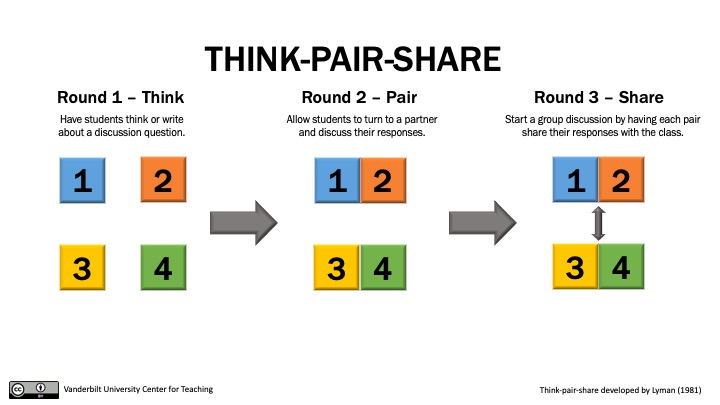

In some situations, certain individuals may dominate conversations while others stay silent. Encourage participation by assigning specific roles, and asking directly for input from quieter participants. Brainstorming techniques can be used like round-robin, think-pair-share, or small groups to ensure equal participation.

5. Conflict Resolution

Conflicts or disagreements may arise during group discussions, leading to stress and uncertainty. To handle conflicts constructively, encourage active listening, acknowledging different perspectives and viewpoints, facilitating open dialogue, and seeking win-win solutions. By creating an open and inclusive space to resolve conflicts, the group’s dynamics and outcomes will enhance positively.

By proactively addressing these common challenges, groups can have meaningful conversations that lead to actionable insights and productive solutions.

Technology and Group Discussions

Technology has revolutionized the way we communicate and collaborate in group settings. With the rise of virtual meetings, video conferencing, and online collaboration tools, it’s now easier than ever to conduct group discussions from anywhere in the world. However, with these benefits come new challenges as well. Here are some ways technology can impact group discussions and how to overcome them.

Pros of Using Technology in Group Discussions

Increased Flexibility and Accessibility : With online tools, group members can join meetings from anywhere, at any time. This allows for greater flexibility and accessibility, making it easier for people to participate in group discussions even if they are not physically present.

Improved Collaboration : Virtual tools allow group members to collaborate in real-time, regardless of their physical location. This makes it easier for members to share ideas and information, and work together to achieve a common goal.

Reduced Costs : Virtual meetings can significantly reduce costs associated with travel and facility rental. This makes it easier for groups with limited resources to conduct discussions without sacrificing the benefits of in-person meetings.

Cons of Using Technology in Group Discussions

Technical Difficulties : Technical difficulties can arise during virtual meetings, which can delay progress and cause frustration. This can be overcome by having all participants test the technology before the meeting and ensuring all participants have a stable internet connection.

Lack of Non-Verbal Cues : During virtual meetings, non-verbal cues such as body language and facial expressions can be difficult to read. To overcome this, group members must be clear and concise with their verbal communication.

Distractions : Since virtual meetings can be conducted from anywhere, it’s easy for participants to become distracted by their surroundings. To overcome this, establish ground rules for participants such as turning off notifications or finding a quiet space to participate in the discussion.

In conclusion, technology has revolutionized the way we conduct group discussions and collaboration. By being aware of the pros and cons of using virtual meetings and online collaboration tools, groups can take advantage of the benefits while mitigating the challenges.

Group discussions are an effective way to promote critical thinking, collaboration, and communication skills . By understanding the different types of group discussions, selecting suitable topics, and implementing effective strategies, educators and students can foster engaging and productive discussions. Remember to establish ground rules, encourage diverse perspectives, and provide structured prompts to make the most out of your group discussions.

Key Takeaways

- Group discussions can take various forms, including case-based and topic-based discussions.

- Choosing a relevant and thought-provoking topic is crucial for effective discussions.

- Strategies such as establishing ground rules and encouraging diverse perspectives enhance the quality of group discussions .

- Active participation and structured discussion prompts facilitate meaningful conversations.

2 thoughts on “Types of Group Discussion: Strategies for Effective Discussions”

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful post. Thanks for providing this information.

Hello growthtactics.net admin, Thanks for the educational content!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Group Discussion: Features, Elements, Types, Process, Characteristics, Roles, Group

- Post author: Anuj Kumar

- Post published: 9 August 2022

- Post category: BBA Study Material / BCOM Study Material / Communication / MBA / MCOM

- Post comments: 0 Comments

Table of Contents

- 1 What is Group Discussion?

- 2.1 Having a Clear Objective

- 2.2 Motivated Interaction

- 2.3 Logical Presentation

- 2.4 Cordial Atmosphere

- 2.5 Effective Communication skills

- 2.6 Participation by all Candidates

- 2.7 Leadership Skills

- 3.1 Purpose

- 3.2 Planning

- 3.3 Participation

- 3.4 Informality

- 3.5 Leadership

- 4.1 Topic Based

- 4.2 Timing of Topic

- 4.3 Case Based

- 5.1 Know the Purpose

- 5.2 Decide Group Members

- 5.3 Seating Arrangements

- 5.4 Give Necessary Instructions

- 5.5 Announcement of Topic

- 5.6 Discussion Time

- 5.7 Assessment

- 6.1 Having a Clear Objective

- 6.2 Motivated Interaction

- 6.3 Logical Presentation

- 6.4 Cordial Atmosphere

- 6.5 Effective Communication Skills

- 6.6 Participation by All Candidates

- 6.7 Leadership Skills

- 7 Roles in Group Discussion

- 8.1 Physical Arrangements

- 8.2 Visual Aids

- 8.3 Group Structure

- 8.4 Organization of Discussion Material

- 8.5 Notice to Participants

- 8.6 Conduct of Discussion

- 8.7 Follow Up

- 9.1 What do you mean by a group discussion?

- 9.2 What are the features of group discussion?

- 9.3 What are the elements of group discussion?

- 9.4 What are the types of group discussions?

- 9.5 What is the process of group discussion?

- 9.6 What are the characteristics of group discussion?

- 9.7 Explain the group discussion problems.

What is Group Discussion?

Group discussion may be defined as a form of a systematic and purposeful oral process characterized by the formal and structured exchange of views on a particular topic, issue, problem, or situation for developing information and understanding essential for decision-making or problem-solving.

Group discussion is an important activity in academic, business, and administrative spheres. It is a systematic and purposeful interactive oral process. Here the exchange of ideas, thoughts, and feelings takes place through oral communication .

The exchange of ideas takes place in a systematic and structured way. The participants sit facing each other almost in a semi-circle and express their views on the given topic/issue/problem.

“Group” is a collection of individuals who have regular contact and frequent interaction and who work together to achieve a common set of goals. “Discussion” is the process whereby two or more people exchange information or ideas in a face-to-face situation to achieve a goal.

The goal, or end product , may be increased knowledge, agreement leading to action, disagreement leading to competition or resolution, or perhaps only a clearing of the air or a continuation of the status quo.

Read Also: What is Group Communication?

Features of Group Discussion

For any group discussion to be successful, achieving group goals is essential. The following features of group discussion :

Having a Clear Objective

Motivated interaction, logical presentation, cordial atmosphere, effective communication skills, participation by all candidates, leadership skills.

The participants need to know the purpose of the group discussion so that they can concentrate during the discussion and contribute to achieving the group goal. An effective group discussion typically begins with a purpose stated by the initiator.

When there is a good level of motivation among the members, they learn to subordinate their personal interests to the group interest and the discussions are more fruitful.

Participants decide how they will organize the presentation of individual views, how an exchange of the views will take place, and how they will reach a group consensus. If the mode of interaction is not decided, few of the members in the group may dominate the discussion and thus will make the entire process meaningless.

The development of a cooperative, friendly, and cordial atmosphere avoids confrontation between the group members.

The success of a group discussion depends on the effective use of communication techniques. Like any other oral communication, clear pronunciations, simple language, and the right pitch are the prerequisites of a group discussion . Non-verbal communication has to be paid attention to since means like body language convey a lot in any communication.

When all the members participate, the group discussion becomes effective. Members need to encourage each other in the group discussion .

Qualities like initiation, logical presentation, encouraging all the group members to participate, and summarizing the discussion reflect leadership qualities.

Read Also: Importance of Group Communication

Elements of Group Discussion

These are the elements of group discussion :

Participation

Informality.

There can be a fruitful discussion without a clear purpose aimless talking is not discussion and no organization and no organization can afford to waste its precious time in aimless talking. Without a clearly stated purpose, the participants are likely to skip from one topic to another.

Following are the purposes of group discussion:

- Your communication skills.

- How do you respond to different situations and your ability to think on your feet?

- Your ability to analyze topics.

- Your knowledge of different subjects.

- Your group dynamics and team skills.

A group cannot rely on the random or on-the-spot expression of feelings and ideas. Advance planning is necessary. The agenda, the notice to members, date, time, and venue of the discussion need to be decided carefully. A meaningful discussion can take place only after careful thought is given to what is to be discussed.

In the group discussion, each individual member is expected to participate and contribute to the deliberation of the group. Members who do not speak in discussion participate through active listening. A meaningful and effective discussion is impossible without participation.

If few persons dominate the discussion rest of the members become passive listeners.

In a discussion, the members should be made to feel comfortable and at ease to speak. An informal and cordial atmosphere encourages the fullest possible participation in the discussion, though group discussion is formal.

A good is essential for a group discussion. The leader initiates and pilots the discussion steering through all troubles. In the absence of a leader, the discussion may run haywire, and the group might become chaotic.

Read Also: Advantages of Group Communication

Types of Group Discussion

Let’s look at the types of group discussion :

Topic Based

Timing of topic.

In this kind of group discussion, participants are expected to discuss a given topic. Many times, especially in the case of the job selection process, participants are given multiple topics and the group can choose any one of them to discuss further. The choice of the final topic is based on the consensus among the group members. A topic for discussion varies from factual to abstract.

The topic for group discussion could be announced either before the date of discussion or on the spot. Pre-announced topics give an opportunity to participants to prepare for discussion while on spot topic checks the presence of mind of the participants. In an on-spot situation, participants are given five to ten minutes to arrange their thoughts.

Sometimes the participants are given a case to discuss upon. The case could be from a real-life situation or a hypothetical one. At the end of the case, a few questions are posed to the participants. All the participants are expected to analyze the case properly and provide the most logical and innovative solution to the question.

Read Also: Characteristics of Group Communication

Process of Group Discussion

These are the steps of the process of group discussion :

Know the Purpose

Decide group members, seating arrangements, give necessary instructions, announcement of topic, discussion time.

Before conducting a group discussion its purpose must be clear to everyone. A purpose could act as a guiding force that can keep the discussion on track. A purpose could also provide a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of the discussion. The purpose for discussion could range from discussing the applicability of a strategy to the selection of a suitable candidate.

In case many participants are there, they need to be divided into smaller groups. So, the next decision is about the number of participants in a group and the number of groups. As suggested earlier, eight to fifteen members per group make it ideal for discussion.

In order to provide a suitable environment for discussion, proper seating arrangements need to be made. A good seating arrangement helps the participants to communicate effectively. As a rule, every member of the group must be in a position to look at and communicate with all the other members of the group. The popular seating arrangement styles are circular and semi-circular styles.

The role of a moderator is to announce necessary instructions prior to the commencement of the discussion. These instructions are given to ensure the smooth conduct of the discussion. Instructions could be related to the time limit for discussion, general rules of conduct, etc.

Now is the time to announce the topic or provide the case for discussion. Generally, at this stage few minutes are provided to the participants to organize their thought. Permission to use pen and paper varies from moderator to moderator.

At this stage, the moderator gives permission to start the discussion. All the participants try to present their viewpoints with supportive arguments on the given topic. One of the members generally initiates the discussion and others start pouring in their views and so on.

Unless and until mutually decided, no particular sequence is followed to present the views. At the conclusion stage, one of the members takes initiative to summarize the discussion in the light of the purpose.

Once the discussion is over the judges evaluate the performance of each member on pre-decided criteria. Such evaluation criteria might include group behavior , communication skills, leadership qualities, analytical skills, subject knowledge, etc.

Characteristics of Group Discussion

Characteristics of group discussion are explained below:

Effective Communication Skills

Participation by all candidates.

Participants decide how they will organize the presentation of individual views, how an exchange of the views will take place, and how they will reach a group consensus. If the mode of interaction is not decided, a few of the members in the group may dominate the discussion and thus will make the entire process meaningless.

The success of a group discussion depends on the effective use of communication techniques. Like any other oral communication, clear pronunciation, simple language, and the right pitch are the prerequisites of a group discussion. Non-verbal communication has to be paid attention to since means like body language convey a lot in any communication.

When all the members participate, the group discussion becomes effective. Members need to encourage each other in the group discussion.

Continue Your Reading: Characteristics of Group Communication

Roles in Group Discussion

At the time of commencement of a group discussion, all the members are on par with each other. Still, all the members assume different roles at different stages during the discussion. The choice of the role assumed by an individual depends upon his/her personal characteristics.

In addition to it, sometimes a member plays more than one role during the discussion. Following is the list of some roles in group discussion :

- Starter: This member initiates the discussion and set the tone for further discussion.

- Connector: This member tries to connect the ideas of all the members of the group.

- Extender: This member extends the viewpoints presented by the previous speaker by adding more information.

- Encourager: This member ensures that all other members are actively participating in the discussion.

- Critic: A critic always provides a significant analysis of the presented idea.

- Peacemaker: If a situation arises where the members of the group are locking horns with each other, this member tries to pacify them to ensure a harmonious discussion.

- Tracker: A tracker keeps the discussion on track and prevents it from going haywire.

Group Discussion Problems

A dialogue between two persons suffers from several barriers. When the number of people increases, there are additional emotional filters, listening inefficiencies, and other problems. Some of the problems involved in group communication are:

Physical Arrangements

Visual aids, group structure, organization of discussion material, notice to participants, conduct of discussion.

The furniture and another physical arrangement for a group discussion should be such that a speaker faces other participants and can maintain eye contact. Each type of discussion group may require a different type of seating arrangement. The room in which the discussion is held should be well-lighted, Well ventilated, and free from noise. Adequate stationery and other material should be provided to the participants.

When the topic of discussion requires consideration of figures and project plans, charts, maps, slides, and other visual aids should be provided to assist the flow of ideas.

Generally, a homogeneous group can Indulge better in the discussion. Mixed groups do not communicate easily. However, all shades of opinion should be represented in the discussion. Members of the group should be selected to ensure a smooth flow of information. The topic of discussion should be within the experience and competence of the group.

The group must know the topic and purpose of the discussion. The scope of the discussion has to be restricted to the time allotted. The discussion sequence (a series of questions to be discussed) must be tentatively planned in advance.

The persons who are to participate in the discussion should be given sufficient time to think over the topic and collect the necessary data and other materials which they want to use in the discussion.

The leader will open the discussion by stating its topic and purpose. He should allow reasonable opportunities for the participants to speak and answer questions. At the end of the discussion, he should summarise the main points of discussion and the conclusions arrived at. Finally, he should thank the members for their contributions to the discussion.

After the discussion, it is necessary to write down the conclusions. A copy may be sent to every participant and other concerned persons. It may be necessary to send notices, letters, etc. to persons who are required to take action on the basis of conclusions arrived in a discussion.

Read More Related Articles

[su_spoiler title=”What is Communication? | Mass Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

What is Communication?

- Meaning of Communication

- Definitions of Communication

- Functions of Communication

- Importance of Communication

- Principles of Communication

- Process of Communication

Types of Communication

- Elements of Communication

- Mass Communication

- What is Mass Communication?

- Definitions of Mass Communication

- Functions of Mass Media

- Characteristics of Mass Communication

- Types of Mass Communication

- Importance of Mass Communication

- Process of Mass Communication

[/su_spoiler]

[su_spoiler title=”Types of Communication | Principles of Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Verbal Communication

- Non-Verbal Communication

Written Communication

- Visual Communication

- Feedback Communication

- Group Communication

- What are the 7 principles of communication?

[su_spoiler title=”Nonverbal Communication | Verbal Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Nonverbal Communication

- What is Nonverbal Communication?

- Advantages of Non verbal Communication

- Disadvantages of Non Verbal Communication

- Functions of Nonverbal Communication

- Types of Nonverbal Communication

- Principles of Nonverbal Communication

- How to Improve Non Verbal Communication Skills

- What is Verbal Communication?

- Types of Verbal Communication

- Functions of Verbal Communication

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Verbal Communication

[su_spoiler title=”Written Communication | Oral Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

- What is Written Communication?

- Ways to Improve Written Communication

- Principles of Written Communication

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Written Communication

Oral Communication

- What is Oral Communication?

- Definitions of Oral Communication

- Importance of Oral Communication

- Methods to Improve Oral Communication Skills

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Oral Communication

- Oral Mode is Used Where

[su_spoiler title=”Business Communication | Organizational Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Business Communication

- What is Business Communication?

- Definition of Business Communication

- Types of Communication in Business

- Importance of Communication in Business

- 7 Cs of Communication in Busi n ess

- 4 P’s of Business Communication

- Purpose of Business Communications

- Barriers to Business Communications

Organizational Communication

- What is Organizational Communication?

- Types of Organizational Communication

- Directions of Organizational Communication

- Importance of Organizational Communication

[su_spoiler title=”Formal Communication | Informal Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Formal Communication

- What is Formal Communication?

- Definition of Formal Communication

- Types of Formal Communication

- Advantages of Formal Communication

- Limitations of Formal Communication

Informal Communication

- What is Informal Communication?

- Types of Informal Communication

- Characteristics of Informal Communication

- Advantages of Informal Communication

- Limitations of Informal Communication

[su_spoiler title=”Interpersonal Communication | Informal Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Interpersonal Communication

- What is Interpersonal Communication?

- Elements of Interpersonal Communication

- Importance of Interpersonal Communication

- Principles of Interpersonal Communication

- 10 Tips for Effective Interpersonal Communication

- Uses of Interpersonal Communication

Development Communication

- What is Development Communication?

- Definitions of Development Communication

- Process of Development Communication

- Functions of Development Communication

- Elements of Development Communication

- 5 Approaches to Development Communication

- Importance of Development Communication

[su_spoiler title=”Downward Communication | Upward Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Downward Communication

- What is Downward Communication?

- Definitions of Downward Communication

- Types of Downward Communication

- Purposes of Downward Communication

- Objectives of Downward Communication

- Advantages of Downward Communication

- Disadvantages of Downward communication

Upward Communication

- What is Upward Communication?

- Definitions of Upward Communication

- Importance of Upward Communication

- Methods of Improving of Upward Communication

- Important Media of Upward Communication

[su_spoiler title=”Barriers to Communication | Horizontal or Lateral Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Barriers to Communication

- What are Barriers to Communication?

- Types of Barriers to Communication

- How to Overcome Barriers of Communication

Horizontal or Lateral Communication

- What is Horizontal Communication?

- Definitions of Horizontal Communication

- Methods of Horizontal Communication

- Advantages of Horizontal Communication

- Disadvantages of Horizontal Communication

[su_spoiler title=”Self Development | Effective Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

Self Development

- What is Self Development?

- Self Development and Communication

- Objectives of Self Development

- Interdependence Between Self Development and Communication

Effective Communication

- What is Effective Communication?

- Characteristics Of Effective Communication

- Importance of Effective Communication

- Essentials for Effective Communication

- Miscommunication

[su_spoiler title=”Difference Between Oral and Written Communication | Theories of Communication” style=”fancy” icon=”plus-circle”]

- Difference Between Oral and Written Communication

Theories of Communication

- What is Theories of Communication?

- Types of Theories of Communication

- Theories Propounded to Create Socio-cultural Background Environment

- Theories based on Ideas of Different Scholars

FAQ Related to Group Discussion

What do you mean by a group discussion, what are the features of group discussion.

Features of group discussion are given below: 1. Having a Clear Objective 2. Motivated Interaction 3. Logical Presentation 4. Cordial Atmosphere 5. Effective Communication skills 6. Participation by all Candidates 7. Leadership Skills.

What are the elements of group discussion?

Elements of group discussion are given below: 1. Purpose 2. Planning 3. Participation 4. Informality 5. Leadership.

What are the types of group discussions?

These are three types of group discussion: 1. Topic Based 2. Timing of Topic 3. Case Based.

What is the process of group discussion?

Processes of group discussion is the given below: 1. Know the Purpose 2. Decide Group Members 3. Seating Arrangements 4. Give Necessary Instructions 5. Announcement of Topic 6. Discussion Time 7. Assessment.

What are the characteristics of group discussion?

Characteristics of group discussion are given below: 1. Having a Clear Objective 2. Motivated Interaction 3. Logical Presentation 4. Cordial Atmosphere 5. Effective Communication Skills 6. Participation by All Candidates 7. Leadership Skills.

Explain the group discussion problems.

These are the group discussion problems: 1. Physical Arrangements 2. Visual Aids 3. Group Structure 4. Organization of Discussion Material 5. Notice to Participants 6. Conduct of Discussion 7. Follow Up.

You Might Also Like

17 ways to overcome barriers to communication.

????[2023] Commercial Laws Notes PDF for BCOM and BBA

Barriers to Communication: Types, and How to Overcome Those Barriers

Essentials of Business Communication

Downward Communication: Definitions, Types, Purposes, Objectives

Written Communication: Definitions, Principal, Types, Advantages and Disadvantages, Ways to Improve

Communication Network: Meaning, Types, Flow of Communication

????[2023] Principles of Financial Accounting Notes PDF for BCOM and BBA

Mathematical and Statistical Techniques Notes PDF | BCOM, BBA

Interpersonal Communication: Elements, Importance, Principles

Scope of Business Communication

????[2023] Financial Accounting Notes PDF for BCOM and BBA

Organizational Communication: Types, Directions, Importance

Horizontal or Lateral Communication: Definitions, Methods, and Advantages and Disadvantages

8 elements of mass communication, 10 steps of process of learning.

Environmental Studies Notes PDF for BCOM and BBA 2023

Group Communication: Meaning, Importance, Advantages, Disadvantages, Characteristics

Mass Communication: Definitions, Functions, Characteristics, Types, Importance, and Process

Cross Cultural Communication: Meaning, Importance, Barriers

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Entrepreneurship

- Organizational Behavior

- Financial Management

- Communication

- Human Resource Management

- Sales Management

- Marketing Management

- Privacy Policy

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 4. Techniques for Leading Group Discussions

Chapter 16 Sections

- Section 1. Conducting Effective Meetings

- Section 2. Developing Facilitation Skills

- Section 3. Capturing What People Say: Tips for Recording a Meeting

- Main Section

A local coalition forms a task force to address the rising HIV rate among teens in the community. A group of parents meets to wrestle with their feeling that their school district is shortchanging its students. A college class in human services approaches the topic of dealing with reluctant participants. Members of an environmental group attend a workshop on the effects of global warming. A politician convenes a “town hall meeting” of constituents to brainstorm ideas for the economic development of the region. A community health educator facilitates a smoking cessation support group.

All of these might be examples of group discussions, although they have different purposes, take place in different locations, and probably run in different ways. Group discussions are common in a democratic society, and, as a community builder, it’s more than likely that you have been and will continue to be involved in many of them. You also may be in a position to lead one, and that’s what this section is about. In this last section of a chapter on group facilitation, we’ll examine what it takes to lead a discussion group well, and how you can go about doing it.

What is an effective group discussion?

The literal definition of a group discussion is obvious: a critical conversation about a particular topic, or perhaps a range of topics, conducted in a group of a size that allows participation by all members. A group of two or three generally doesn’t need a leader to have a good discussion, but once the number reaches five or six, a leader or facilitator can often be helpful. When the group numbers eight or more, a leader or facilitator, whether formal or informal, is almost always helpful in ensuring an effective discussion.

A group discussion is a type of meeting, but it differs from the formal meetings in a number of ways: It may not have a specific goal – many group discussions are just that: a group kicking around ideas on a particular topic. That may lead to a goal ultimately...but it may not. It’s less formal, and may have no time constraints, or structured order, or agenda. Its leadership is usually less directive than that of a meeting. It emphasizes process (the consideration of ideas) over product (specific tasks to be accomplished within the confines of the meeting itself. Leading a discussion group is not the same as running a meeting. It’s much closer to acting as a facilitator, but not exactly the same as that either.

An effective group discussion generally has a number of elements:

- All members of the group have a chance to speak, expressing their own ideas and feelings freely, and to pursue and finish out their thoughts

- All members of the group can hear others’ ideas and feelings stated openly

- Group members can safely test out ideas that are not yet fully formed

- Group members can receive and respond to respectful but honest and constructive feedback. Feedback could be positive, negative, or merely clarifying or correcting factual questions or errors, but is in all cases delivered respectfully.

- A variety of points of view are put forward and discussed

- The discussion is not dominated by any one person

- Arguments, while they may be spirited, are based on the content of ideas and opinions, not on personalities

- Even in disagreement, there’s an understanding that the group is working together to resolve a dispute, solve a problem, create a plan, make a decision, find principles all can agree on, or come to a conclusion from which it can move on to further discussion

Many group discussions have no specific purpose except the exchange of ideas and opinions. Ultimately, an effective group discussion is one in which many different ideas and viewpoints are heard and considered. This allows the group to accomplish its purpose if it has one, or to establish a basis either for ongoing discussion or for further contact and collaboration among its members.

There are many possible purposes for a group discussion, such as:

- Create a new situation – form a coalition, start an initiative, etc.

- Explore cooperative or collaborative arrangements among groups or organizations

- Discuss and/or analyze an issue, with no specific goal in mind but understanding

- Create a strategic plan – for an initiative, an advocacy campaign, an intervention, etc.

- Discuss policy and policy change

- Air concerns and differences among individuals or groups

- Hold public hearings on proposed laws or regulations, development, etc.

- Decide on an action

- Provide mutual support

- Solve a problem

- Resolve a conflict

- Plan your work or an event

Possible leadership styles of a group discussion also vary. A group leader or facilitator might be directive or non-directive; that is, she might try to control what goes on to a large extent; or she might assume that the group should be in control, and that her job is to facilitate the process. In most group discussions, leaders who are relatively non-directive make for a more broad-ranging outlay of ideas, and a more satisfying experience for participants.

Directive leaders can be necessary in some situations. If a goal must be reached in a short time period, a directive leader might help to keep the group focused. If the situation is particularly difficult, a directive leader might be needed to keep control of the discussion and make

Why would you lead a group discussion?

There are two ways to look at this question: “What’s the point of group discussion?” and “Why would you, as opposed to someone else, lead a group discussion?” Let’s examine both.

What’s the point of group discussion?

As explained in the opening paragraphs of this section, group discussions are common in a democratic society. There are a number of reasons for this, some practical and some philosophical.

A group discussion:

- G ives everyone involved a voice . Whether the discussion is meant to form a basis for action, or just to play with ideas, it gives all members of the group a chance to speak their opinions, to agree or disagree with others, and to have their thoughts heard. In many community-building situations, the members of the group might be chosen specifically because they represent a cross-section of the community, or a diversity of points of view.

- Allows for a variety of ideas to be expressed and discussed . A group is much more likely to come to a good conclusion if a mix of ideas is on the table, and if all members have the opportunity to think about and respond to them.

- Is generally a democratic, egalitarian process . It reflects the ideals of most grassroots and community groups, and encourages a diversity of views.

- Leads to group ownership of whatever conclusions, plans, or action the group decides upon . Because everyone has a chance to contribute to the discussion and to be heard, the final result feels like it was arrived at by and belongs to everyone.

- Encourages those who might normally be reluctant to speak their minds . Often, quiet people have important things to contribute, but aren’t assertive enough to make themselves heard. A good group discussion will bring them out and support them.

- Can often open communication channels among people who might not communicate in any other way . People from very different backgrounds, from opposite ends of the political spectrum, from different cultures, who may, under most circumstances, either never make contact or never trust one another enough to try to communicate, might, in a group discussion, find more common ground than they expected.

- Is sometimes simply the obvious, or even the only, way to proceed. Several of the examples given at the beginning of the section – the group of parents concerned about their school system, for instance, or the college class – fall into this category, as do public hearings and similar gatherings.

Why would you specifically lead a group discussion?

You might choose to lead a group discussion, or you might find yourself drafted for the task. Some of the most common reasons that you might be in that situation:

- It’s part of your job . As a mental health counselor, a youth worker, a coalition coordinator, a teacher, the president of a board of directors, etc. you might be expected to lead group discussions regularly.

- You’ve been asked to . Because of your reputation for objectivity or integrity, because of your position in the community, or because of your skill at leading group discussions, you might be the obvious choice to lead a particular discussion.

- A discussion is necessary, and you’re the logical choice to lead it . If you’re the chair of a task force to address substance use in the community, for instance, it’s likely that you’ll be expected to conduct that task force’s meetings, and to lead discussion of the issue.

- It was your idea in the first place . The group discussion, or its purpose, was your idea, and the organization of the process falls to you.

You might find yourself in one of these situations if you fall into one of the categories of people who are often tapped to lead group discussions. These categories include (but aren’t limited to):

- Directors of organizations

- Public officials

- Coalition coordinators

- Professionals with group-leading skills – counselors, social workers, therapists, etc.

- Health professionals and health educators

- Respected community members. These folks may be respected for their leadership – president of the Rotary Club, spokesperson for an environmental movement – for their positions in the community – bank president, clergyman – or simply for their personal qualities – integrity, fairness, ability to communicate with all sectors of the community.

- Community activists. This category could include anyone from “professional” community organizers to average citizens who care about an issue or have an idea they want to pursue.

When might you lead a group discussion?

The need or desire for a group discussion might of course arise anytime, but there are some times when it’s particularly necessary.

- At the start of something new . Whether you’re designing an intervention, starting an initiative, creating a new program, building a coalition, or embarking on an advocacy or other campaign, inclusive discussion is likely to be crucial in generating the best possible plan, and creating community support for and ownership of it.

- When an issue can no longer be ignored . When youth violence reaches a critical point, when the community’s drinking water is declared unsafe, when the HIV infection rate climbs – these are times when groups need to convene to discuss the issue and develop action plans to swing the pendulum in the other direction.

- When groups need to be brought together . One way to deal with racial or ethnic hostility, for instance, is to convene groups made up of representatives of all the factions involved. The resulting discussions – and the opportunity for people from different backgrounds to make personal connections with one another – can go far to address everyone’s concerns, and to reduce tensions.

- When an existing group is considering its next step or seeking to address an issue of importance to it . The staff of a community service organization, for instance, may want to plan its work for the next few months, or to work out how to deal with people with particular quirks or problems.

How do you lead a group discussion?

In some cases, the opportunity to lead a group discussion can arise on the spur of the moment; in others, it’s a more formal arrangement, planned and expected. In the latter case, you may have the chance to choose a space and otherwise structure the situation. In less formal circumstances, you’ll have to make the best of existing conditions.

We’ll begin by looking at what you might consider if you have time to prepare. Then we’ll examine what it takes to make an effective discussion leader or facilitator, regardless of external circumstances.

Set the stage

If you have time to prepare beforehand, there are a number of things you may be able to do to make the participants more comfortable, and thus to make discussion easier.

Choose the space

If you have the luxury of choosing your space, you might look for someplace that’s comfortable and informal. Usually, that means comfortable furniture that can be moved around (so that, for instance, the group can form a circle, allowing everyone to see and hear everyone else easily). It may also mean a space away from the ordinary.

One organization often held discussions on the terrace of an old mill that had been turned into a bookstore and café. The sound of water from the mill stream rushing by put everyone at ease, and encouraged creative thought.

Provide food and drink

The ultimate comfort, and one that breaks down barriers among people, is that of eating and drinking.

Bring materials to help the discussion along

Most discussions are aided by the use of newsprint and markers to record ideas, for example.

Become familiar with the purpose and content of the discussion

If you have the opportunity, learn as much as possible about the topic under discussion. This is not meant to make you the expert, but rather to allow you to ask good questions that will help the group generate ideas.

Make sure everyone gets any necessary information, readings, or other material beforehand

If participants are asked to read something, consider questions, complete a task, or otherwise prepare for the discussion, make sure that the assignment is attended to and used. Don’t ask people to do something, and then ignore it.

Lead the discussion

Think about leadership style

The first thing you need to think about is leadership style, which we mentioned briefly earlier in the section. Are you a directive or non-directive leader? The chances are that, like most of us, you fall somewhere in between the extremes of the leader who sets the agenda and dominates the group completely, and the leader who essentially leads not at all. The point is made that many good group or meeting leaders are, in fact, facilitators, whose main concern is supporting and maintaining the process of the group’s work. This is particularly true when it comes to group discussion, where the process is, in fact, the purpose of the group’s coming together.

A good facilitator helps the group set rules for itself, makes sure that everyone participates and that no one dominates, encourages the development and expression of all ideas, including “odd” ones, and safeguards an open process, where there are no foregone conclusions and everyone’s ideas are respected. Facilitators are non-directive, and try to keep themselves out of the discussion, except to ask questions or make statements that advance it. For most group discussions, the facilitator role is probably a good ideal to strive for.

It’s important to think about what you’re most comfortable with philosophically, and how that fits what you’re comfortable with personally. If you’re committed to a non-directive style, but you tend to want to control everything in a situation, you may have to learn some new behaviors in order to act on your beliefs.

Put people at ease

Especially if most people in the group don’t know one another, it’s your job as leader to establish a comfortable atmosphere and set the tone for the discussion.

Help the group establish ground rules

The ground rules of a group discussion are the guidelines that help to keep the discussion on track, and prevent it from deteriorating into namecalling or simply argument. Some you might suggest, if the group has trouble coming up with the first one or two:

- Everyone should treat everyone else with respect : no name-calling, no emotional outbursts, no accusations.

- No arguments directed at people – only at ideas and opinions . Disagreement should be respectful – no ridicule.

- Don’t interrupt . Listen to the whole of others’ thoughts – actually listen, rather than just running over your own response in your head.

- Respect the group’s time . Try to keep your comments reasonably short and to the point, so that others have a chance to respond.

- Consider all comments seriously, and try to evaluate them fairly . Others’ ideas and comments may change your mind, or vice versa: it’s important to be open to that.

- Don’t be defensive if someone disagrees with you . Evaluate both positions, and only continue to argue for yours if you continue to believe it’s right.

- Everyone is responsible for following and upholding the ground rules .

Ground rules may also be a place to discuss recording the session. Who will take notes, record important points, questions for further discussion, areas of agreement or disagreement? If the recorder is a group member, the group and/or leader should come up with a strategy that allows her to participate fully in the discussion.

Generate an agenda or goals for the session

You might present an agenda for approval, and change it as the group requires, or you and the group can create one together. There may actually be no need for one, in that the goal may simply be to discuss an issue or idea. If that’s the case, it should be agreed upon at the outset.

How active you are might depend on your leadership style, but you definitely have some responsibilities here. They include setting, or helping the group to set the discussion topic; fostering the open process; involving all participants; asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion; summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, and ideas; and wrapping up the session. Let’s look at these, as well as some do’s and don’t’s for discussion group leaders.

- Setting the topic . If the group is meeting to discuss a specific issue or to plan something, the discussion topic is already set. If the topic is unclear, then someone needs to help the group define it. The leader – through asking the right questions, defining the problem, and encouraging ideas from the group – can play that role.

- Fostering the open process . Nurturing the open process means paying attention to the process, content, and interpersonal dynamics of the discussion all at the same time – not a simple matter. As leader, your task is not to tell the group what to do, or to force particular conclusions, but rather to make sure that the group chooses an appropriate topic that meets its needs, that there are no “right” answers to start with (no foregone conclusions), that no one person or small group dominates the discussion, that everyone follows the ground rules, that discussion is civil and organized, and that all ideas are subjected to careful critical analysis. You might comment on the process of the discussion or on interpersonal issues when it seems helpful (“We all seem to be picking on John here – what’s going on?”), or make reference to the open process itself (“We seem to be assuming that we’re supposed to believe X – is that true?”). Most of your actions as leader should be in the service of modeling or furthering the open process.

Part of your job here is to protect “minority rights,” i.e., unpopular or unusual ideas. That doesn’t mean you have to agree with them, but that you have to make sure that they can be expressed, and that discussion of them is respectful, even in disagreement. (The exceptions are opinions or ideas that are discriminatory or downright false.) Odd ideas often turn out to be correct, and shouldn’t be stifled.

- Involving all participants . This is part of fostering the open process, but is important enough to deserve its own mention. To involve those who are less assertive or shy, or who simply can’t speak up quickly enough, you might ask directly for their opinion, encourage them with body language (smile when they say anything, lean and look toward them often), and be aware of when they want to speak and can’t break in. It’s important both for process and for the exchange of ideas that everyone have plenty of opportunity to communicate their thoughts.

- Asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion . The leader should be aware of the progress of the discussion, and should be able to ask questions or provide information or arguments that stimulate thinking or take the discussion to the next step when necessary. If participants are having trouble grappling with the topic, getting sidetracked by trivial issues, or simply running out of steam, it’s the leader’s job to carry the discussion forward.

This is especially true when the group is stuck, either because two opposing ideas or factions are at an impasse, or because no one is able or willing to say anything. In these circumstances, the leader’s ability to identify points of agreement, or to ask the question that will get discussion moving again is crucial to the group’s effectiveness.

- Summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, or ideas . This task entails making sure that everyone understands a point that was just made, or the two sides of an argument. It can include restating a conclusion the group has reached, or clarifying a particular idea or point made by an individual (“What I think I heard you say was…”). The point is to make sure that everyone understands what the individual or group actually meant.

- Wrapping up the session . As the session ends, the leader should help the group review the discussion and make plans for next steps (more discussion sessions, action, involving other people or groups, etc.). He should also go over any assignments or tasks that were agreed to, make sure that every member knows what her responsibilities are, and review the deadlines for those responsibilities. Other wrap-up steps include getting feedback on the session – including suggestions for making it better – pointing out the group’s accomplishments, and thanking it for its work.

Even after you’ve wrapped up the discussion, you’re not necessarily through. If you’ve been the recorder, you might want to put the notes from the session in order, type them up, and send them to participants. The notes might also include a summary of conclusions that were reached, as well as any assignments or follow-up activities that were agreed on.