HOLIDAY SAVINGS: Save 30% Sitewide with HOL30 + free shipping on orders over $75.

On The Site

“Laboratory of Experimental Psychology” by Popular Science Monthly Volume, licensed for use on Wikimedia Commons .

Exploring the Bystander Effect

May 1, 2017 | yalepress | Current Affairs , Psychology

Joel E. Dimsdale—

The very public murder of young Kitty Genovese in New York City motivated the next social psychology exploration on the nature of malice. On the night of March 13, 1964, Genovese left work and was walking on a street in Kew Gardens, Queens, when she was chased down and stabbed. The murder was doubly horrific. She didn’t die suddenly; rather, her assailant kept chasing her, stabbing and slashing her over and over again in an attack that lasted more than thirty minutes. She called out in terror: “Please help me! Please help me!” But no one did.

Two investigators, John Darley and Bibb Latané, designed a series of experiments to find out why people do not intervene even in life-threatening situations. If Milgram conducted his studies on the infl uence of authority, looking over his shoulder at Nazi Germany, Darley and Latané wanted to learn what accounts for bystander apathy. Why did no one intervene to save Genovese’s life? Why did so many people stand by and do nothing to save the lives of Nazi victims? It was a topic Hannah Arendt had wrestled with in another context: “Under conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not. . . . No more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation.” Sadly, the number of people who resist complying is small.

To be fair, emergency situations are often sudden, ambiguous, and out of the typical life experience of the beholder. But, as Darley and Latané would learn, there was something about the social environment itself that influences how a person would respond to emergencies. Painstakingly, first at Columbia University and New York University and then at Princeton University, the investigators grappled with this problem in multiple experiments.

Darley and Latané confronted their subjects with a threatening situation and assessed how the subjects would respond. Then, in an ingenious twist, Darley and Latané studied the subject alone or else in small groups. How would a subject respond to an emergency in the presence of other people who appeared to ignore what was happening?

In one experiment, subjects reported to a room to talk about the problems of urban life while smoke poured from the room’s heating register—not just a few puffs, but so much smoke that by the end of the session “vision was obscured in the room by the amount of smoke present.” When subjects waited alone, 75 percent of them quickly reported the smoke, but when they entered a room with two other seated people who studiously ignored the smoke, the subjects’ behavior was strikingly different. Only 10 percent of these subjects reported the smoke even though they “coughed, rubbed their eyes, and opened the window.”

In another experiment, subjects arrived at the lab and were greeted by a receptionist who stood up, drew a curtain, and noisily clambered up on a chair to grab some folders. The receptionist surreptitiously turned on a tape recorder, which played the sound of a loud crash, a scream, and the following script: “Oh, my God, my foot . . . I . . . can’t move . . . it. Oh . . . my ankle, I can’t get this . . . thing . . . off me.” The tape played sounds of weeping and moaning. Here again, the question was simple: Would anyone check on the receptionist, and how long would it take? It may be comforting that 70 percent of the subjects who waited alone checked on the receptionist. It will not be comforting to learn that when the subjects were waiting with a stranger who ignored the receptionist’s plight, only 7 percent of the subjects intervened.

A third experiment revealed even more indifference. In this setting, subjects were ushered into individual cubicles and asked to talk via intercom with other subjects about the problems they experienced in college. One subject, secretly a confederate of the investigators, revealed that in addition to all the usual stresses of college, he was embarrassed because he had a seizure disorder. He then grew increasingly incoherent, saying: “I-er-umI think I-I need-er-if-if could-er-er-somebody er-er-er-er-er-er-er give me a little-er-give me a little help here because-er-I-er-I’m-er-er h-h-having a-a-a real problem-er-right now and I-er-if somebody could help me out it wouldit would-er-er s-s-sure be-sure be good . . . because-er-there-er-er-a cause I-er-I-uh-I’ve got a-a one of the-er sei—-er-er-things coming on and-and-and I could really-er-use some help so if somebody would-er give me a little hhelp-er-uh-uh-uh (choking sounds). . . . I’m gonna die-er-er I’m . . . gonna die-er-help-er-er-seizure-er (chokes, then quiet).”

When subjects were alone in the cubicle, 85 percent got up within a minute to check on the subject who was presumably having a seizure. Subjects were then tested with other people in the same cubicle. If the subject was paired with one person who had been secretly instructed to ignore the situation, 62 percent of the subjects got up to check on the presumably ill student. If however, the subject was tested with four confederates who ignored the apparent seizure, then the chance of the subject responding fell to only 31 percent, and it took such people, on average, three minutes to check on their fellow student.

There have been countless variations on the design, but the inherent message remains the same: in social situations, there is a diffusion of responsibility. If a bystander sees that other witnesses are doing nothing, then he or she will also do nothing—“bystander apathy,” as Darley and Latané put it so pungently.

From Anatomy of Malice by Joel E. Dimsdale , published by Yale University Press in 2016. Reproduced by permission.

Joel E. Dimsdale is distinguished professor emeritus and research professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He lives in San Diego, CA.

Further Reading

Recent Posts

- Italian Futurism and Avant-Garde Sculpture

- The Great Transformation: A Conversation with Odd Arne Westad and Jian Chen

- A Conversation with Susan Owens about Drawing and the History of Art

- Trump and His Allies Could Corrupt Future Elections

- Where We Stand: A Conversation with Djamila Ribeiro and Padma Viswanathan

- Formation of a New Language: Chicago, 1943-56

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact W.W. Norton to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

Bystander Effect In Psychology

Udochi Emeghara

Research Assistant at Harvard University

B.A., Neuroscience, Harvard University

Udochi Emeghara is a research assistant at the Harvard University Stress and Development Lab.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Take-home Messages

- The bystander effect is a social psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help a victim when others are present. The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely any one of them is to help.

- Factors include diffusion of responsibility and the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways.

- The most frequently cited real-life example of the bystander effect regards a young woman called Kitty Genovese , who was murdered in Queens, New York, in 1964 while several of her neighbors looked on. No one intervened until it was too late.

- Notice the event (or in a hurry and not notice).

- Interpret the situation as an emergency (or assume that as others are not acting, it is not an emergency).

- Assume responsibility (or assume that others will do this).

- Know what to do (or not have the skills necessary to help).

- Decide to help (or worry about danger, legislation, embarrassment, etc.).

- Latané and Darley (1970) identified three different psychological processes that might prevent a bystander from helping a person in distress: (i) diffusion of responsibility; (ii) evaluation apprehension (fear of being publically judged); and (iii) pluralistic ignorance (the tendency to rely on the overt reactions of others when defining an ambiguous situation).

- Diffusion of responsibility refers to the tendency to subjectively divide personal responsibility to help by the number of bystanders present. Bystanders are less likely to intervene in emergency situations as the size of the group increases, and they feel less personal responsibility.

What is the bystander effect?

The term bystander effect refers to the tendency for people to be inactive in high-danger situations due to the presence of other bystanders (Darley & Latané, 1968; Latané & Darley, 1968, 1970; Latané & Nida, 1981).

Thus, people tend to help more when alone than in a group.

The implications of this theory have been widely studied by a variety of researchers, but initial interest in this phenomenon arose after the brutal murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese in 1964.

Through a series of experiments beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, the bystander effect phenomenon has become more widely understood.

Kitty Genovese

On the morning of March 13, 1964, Kitty Genovese returned to her apartment complex, at 3 am, after finishing her shift at a local bar.

After parking her car in a lot adjacent to her apartment building, she began walking a short distance to the entrance, which was located at the back of the building.

As she walked, she noticed a figure at the far end of the lot. She shifted directions and headed towards a different street, but the man followed and seized her.

As she yelled, neighbors from the apartment building went to the window and watched as he stabbed her. A man from the apartment building yelled down, “Let that girl alone!” (New York Times, 1964).

Following this, the assailant appeared to have left, but once the lights from the apartments turned off, the perpetrator returned and stabbed Kitty Genovese again. Once again, the lights came on, and the windows opened, driving the assaulter away from the scene.

Unfortunately, the assailant returned and stabbed Catherine Genovese for the final time. The first call to the police came in at 3:50 am, and the police arrived in two minutes.

When the neighbors were asked why they did not intervene or call the police earlier, some answers were “I didn”t want to get involved”; “Frankly, we were afraid”; “I was tired. I went back to bed.” (New York Times, 1964).

After this initial report, the case was launched to nationwide attention, with various leaders commenting on the apparent “moral decay” of the country.

In response to these claims, Darley and Latané set out to find an alternative explanation.

Decision Model of Helping

Latané & Darley (1970) formulated a five-stage model to explain why bystanders in emergencies sometimes do and sometimes do not offer help.

At each stage in the model, the answer ‘No’ results in no help being given, while the answer ‘yes’ leads the individual closer to offering help.

However, they argued that helping responses may be inhibited at any stage of the process. For example, the bystander may not notice the situation or the situation may be ambiguous and not readily interpretable as an emergency.

The five stages are:

- The bystander must notice that something is amiss.

- The bystander must define that situation as an emergency.

- The bystander must assess how personally responsible they feel.

- The bystander must decide how best to offer assistance.

- The bystander must act on that decision.

Figure 1. Decision Model of Helping by Latané and Darley (1970).

Why does the bystander effect occur?

Latane´ and Darley (1970) identified three different psychological processes that might interfere with the completion of this sequence.

Diffusion of Responsibility

The first process is a diffusion of responsibility, which refers to the tendency to subjectively divide the personal responsibility to help by the number of bystanders.

Diffusion of responsibility occurs when a duty or task is shared between a group of people instead of only one person.

Whenever there is an emergency situation in which more than one person is present, there is a diffusion of responsibility. There are three ideas that categorize this phenomenon:

- The moral obligation to help does not fall only on one person but the whole group that is witnessing the emergency.

- The blame for not helping can be shared instead of resting on only one person.

- The belief that another bystander in the group will offer help.

Darley and Latané (1968) tested this hypothesis by engineering an emergency situation and measuring how long it took for participants to get help.

College students were ushered into a solitary room under the impression that a conversation centered around learning in a “high-stress, high urban environment” would ensue.

This discussion occurred with “other participants” that were in their own room as well (the other participants were just records playing). Each participant would speak one at a time into a microphone.

After a round of discussion, one of the participants would have a “seizure” in the middle of the discussion; the amount of time that it took the college student to obtain help from the research assistant that was outside of the room was measured. If the student did not get help after six minutes, the experiment was cut off.

Darley and Latané (1968) believed that the more “people” there were in the discussion, the longer it would take subjects to get help.

The results were in line with that hypothesis. The smaller the group, the more likely the “victim” was to receive timely help.

Still, those who did not get help showed signs of nervousness and concern for the victim. The researchers believed that the signs of nervousness highlight that the college student participants were most likely still deciding the best course of action; this contrasts with the leaders of the time who believed inaction was due to indifference.

This experiment showcased the effect of diffusion of responsibility on the bystander effect.

Evaluation Apprehension

The second process is evaluation apprehension, which refers to the fear of being judged by others when acting publicly.

People may also experience evaluation apprehension and fear of losing face in front of other bystanders.

Individuals may feel afraid of being superseded by a superior helper, offering unwanted assistance, or facing the legal consequences of offering inferior and possibly dangerous assistance.

Individuals may decide not to intervene in critical situations if they are afraid of being superseded by a superior helper, offering unwanted assistance, or facing the legal consequences of offering inferior and possibly dangerous assistance.

Pluralistic Ignorance

The third process is pluralistic ignorance, which results from the tendency to rely on the overt reactions of others when defining an ambiguous situation.

Pluralistic ignorance occurs when a person disagrees with a certain type of thinking but believes that everyone else adheres to it and, as a result, follows that line of thinking even though no one believes it.

Deborah A. Prentice cites an example of this. Despite being in a difficult class, students may not raise their hands in response to the lecturer asking for questions.

This is often due to the belief that everyone else understands the material, so for fear of looking inadequate, no one asks clarifying questions.

It is this type of thinking that explains the effect of pluralistic ignorance on the bystander effect. The overarching idea is uncertainty and perception. What separates pluralistic ignorance is the ambiguousness that can define a situation.

If the situation is clear (for the classroom example: someone stating they do not understand), pluralistic ignorance would not apply (since the person knows that someone else agrees with their thinking).

It is the ambiguity and uncertainty which leads to incorrect perceptions that categorize pluralistic ignorance.

Rendsvig (2014) proposes an eleven-step process to explain this phenomenon.

These steps follow the perspective of a bystander (who will be called Bystander A) amidst a group of other bystanders in an emergency situation.

- Bystander A is present in a specific place. Nothing has happened.

- A situation occurs that is ambiguous in nature (it is not certain what has occurred or what the ramifications of the event are), and Bystander A notices it.

- Bystander A believes that this is an emergency situation but is unaware of how the rest of the bystanders perceive the situation.

- A course of action is taken. This could be a few things like charging into the situation or calling the police, but in pluralistic ignorance, Bystander A chooses to understand more about the situation by looking around and taking in the reactions of others.

- As observation takes place, Bystander A is not aware that the other bystanders may be doing the same thing. Thus, when surveying others’ reactions, Bystander A “misperceives” the other bystanders” observation of the situation as purposeful inaction.

- As Bystander A notes the reaction of the others, Bystander A puts the reaction of the other bystanders in context.

- Bystander A then believes that the inaction of others is due to their belief that an emergency situation is not occurring.

- Thus, Bystander A believes that there is an accident but also believes that others do not perceive the situation as an emergency. Bystander A then changes their initial belief.

- Bystander A now believes that there is no emergency.

- Bystander A has another opportunity to help.

- Bystander A chooses not to help because of the belief that there is no emergency.

Pluralistic ignorance operates under the assumption that all the other bystanders are also going through these eleven steps.

Thus, they all choose not to help due to the misperception of others’ reactions to the same situation.

Other Explanations

While these three are the most widely known explanations, there are other theories that could also play a role. One example is a confusion of responsibility.

Confusion of responsibility occurs when a bystander fears that helping could lead others to believe that they are the perpetrator. This fear can cause people to not act in dire situations.

Another example is priming. Priming occurs when a person is given cues that will influence future actions. For example, if a person is given a list of words that are associated with home decor and furniture and then is asked to give a five-letter word, answers like chair or table would be more likely than pasta.

In social situations, Garcia et al. found that simply thinking of being in a group could lead to lower rates of helping in emergency situations. This occurs because groups are often associated with “being lost in a crowd, being deindividuated, and having a lowered sense of personal accountability” (Garcia et al., 2002, p. 845).

Thus, the authors argue that the way a person was primed could also influence their ability to help. These alternate theories highlight the fact that the bystander effect is a complex phenomenon that encompasses a variety of ideologies.

Bystander Experiments

In one of the first experiments of this type, Latané & Darley (1968) asked participants to sit on their own in a room and complete a questionnaire on the pressures of urban life.

Smoke (actually steam) began pouring into the room through a small wall vent. Within two minutes, 50 percent had taken action, and 75 percent had acted within six minutes when the experiment ended.

In groups of three participants, 62 percent carried on working for the entire duration of the experiment.

In interviews afterward, participants reported feeling hesitant about showing anxiety, so they looked to others for signs of anxiety. But since everyone was trying to appear calm, these signs were not evident, and therefore they believed that they must have misinterpreted the situation and redefined it as ‘safe.’

This is a clear example of pluralistic ignorance, which can affect the answer at step 2 of the Latané and Darley decision model above.

Genuine ambiguity can also affect the decision-making process. Shotland and Straw (1976) conducted an interesting experiment that illustrated this.

They hypothesized that people would be less willing to intervene in a situation of domestic violence (where a relationship exists between the two people) than in a situation involving violence involving two strangers. Male participants were shown a staged fight between a man and a woman.

In one condition, the woman screamed, ‘I don’t even know you,’ while in another, she screamed, ‘I don’t even know why I married you.’

Three times as many men intervened in the first condition as in the second condition. Such findings again provide support for the decision model in terms of the decisions made at step 3 in the process.

People are less likely to intervene if they believe that the incident does not require their personal responsibility.

Critical Evaluation

While the bystander effect has become a cemented theory in social psychology, the original account of the murder of Catherine Genovese has been called into question. By casting doubt on the original case, the implications of the Darley and Latané research are also questioned.

Manning et al. (2007) did this through their article “The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping, The parable of the 38 witnesses”. By examining the court documents and legal proceedings from the case, the authors found three points that deviate from the traditional story told.

While it was originally claimed that thirty-eight people witnessed this crime, in actuality, only a few people physically saw Kitty Genovese and her attacker; the others just heard the screams from Kitty Genovese.

In addition, of those who could see, none actually witnessed the stabbing take place (although one of the people who testified did see a violent action on behalf of the attacker.)

This contrasts with the widely held notion that all 38 people witnessed the initial stabbing.

Lastly, the second stabbing that resulted in the death of Catherine Genovese occurred in a stairwell which was not in the view of most of the initial witnesses; this deviates from the original article that stated that the murder took place on Austin Street in New York City in full view of at least 38 people.

This means that they would not have been able to physically see the murder take place. The potential inaccurate reporting of the initial case has not negated the bystander effect completely, but it has called into question its applicability and the incomplete nature of research concerning it.

Limitations of the Decision-Helping Model

Schroeder et al. (1995) believe that the decision-helping model provides a valuable framework for understanding bystander intervention.

Although primarily developed to explain emergency situations, it has been applied to other situations, such as preventing someone from drinking and driving, to deciding to donate a kidney to a relative.

However, the decision model does not provide a complete picture. It fails to explain why ‘no’ decisions are made at each stage of the decision tree. This is particularly true after people have originally interpreted the event as an emergency.

The decision model doesn’t take into account emotional factors such as anxiety or fear, nor does it focus on why people do help; it mainly concentrates on why people don’t help.

Piliavin et al. (1969, 1981) put forward the cost–reward arousal model as a major alternative to the decision model and involves evaluating the consequences of helping or not helping.

Whether one helps or not depends on the outcome of weighing up both the costs and rewards of helping. The costs of helping include effort, time, loss of resources, risk of harm, and negative emotional response.

The rewards of helping include fame, gratitude from the victim and relatives, and self-satisfaction derived from the act of helping. It is recognized that costs may be different for different people and may even differ from one occasion to another for the same person.

Accountability Cues

According to Bommel et al. (2012), the negative account of the consequences of the bystander effect undermines the potential positives. The article “Be aware to care: Public self-awareness leads to a reversal of the bystander effect” details how crowds can actually increase the amount of aid given to a victim under certain circumstances.

One of the problems with bystanders in emergency situations is the ability to split the responsibility (diffusion of responsibility).

Yet, when there are “accountability cues,” people tend to help more. Accountability cues are specific markers that let the bystander know that their actions are being watched or highlighted, like a camera. In a series of experiments, the researchers tested if the bystander effect could be reversed using these cues.

An online forum that was centered around aiding those with “severe emotional distress” (Bommel et al., 2012) was created.

The participants in the study responded to specific messages from visitors of the forum and then rated how visible they felt on the forum.

The researchers postulated that when there were no accountability cues, people would not give as much help and would not rate themselves as being very visible on the forum; when there are accountability cues (using a webcam and highlighting the name of the forum visitor), not only would more people help but they would also rate themselves as having a higher presence on the forum.

As expected, the results fell in line with these theories. Thus, targeting one’s reputation through accountability cues could increase the likelihood of helping. This shows that there are potential positives to the bystander effect.

Neuroimaging Evidence

Researchers looked at the regions of the brain that were active when a participant witnessed emergencies. They noticed that less activity occurred in the regions that facilitate helping: the pre- and postcentral gyrus and the medial prefrontal cortex (Hortensius et al., 2018).

Thus, one’s initial biological response to an emergency situation is inaction due to personal fear. After that initial fear, sympathy arises, which prompts someone to go to the aid of the victim. These two systems work in opposition; whichever overrides the other determines the action that will be taken.

If there is more sympathy than personal distress, the participant will help. Thus, these researchers argue that the decision to help is not “reflective” but “reflexive” (Hortensius et al., 2018).

With this in mind, the researchers argue for a more personalized view that takes into account one’s personality and disposition to be more sympathetic rather than utilize a one-size-fits-all overgeneralization.

Darley, J. M., & Latané´, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 , 377–383.

Garcia, Stephen M, Weaver, Kim, Moskowitz, Gordon B, & Darley, John M. (2002). Crowded Minds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (4), 843-853.

Hortensius, Ruud, & De Gelder, Beatrice. (2018). From Empathy to Apathy: The Bystander Effect Revisited. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27 (4), 249-256.

Latané´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10 , 215–221.

Latané´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Croft.

Latané´, B., & Darley, J. M. (1976). Help in a crisis: Bystander response to an emergency . Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Latané´, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping . Psychological Bulletin, 89 , 308 –324.

Manning, R., Levine, M., & Collins, A. (2007). The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses. American Psychologist, 62 , 555-562.

Prentice, D. (2007). Pluralistic ignorance. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 674-674) . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Rendsvig, R. K. (2014). Pluralistic ignorance in the bystander effect: Informational dynamics of unresponsive witnesses in situations calling for intervention. Synthese (Dordrecht), 191 (11), 2471-2498.

Shotland, R. L., & Straw, M. K. (1976). Bystander response to an assault: When a man attacks a woman. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 (5), 990.

Siegal, H. A. (1972). The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? 1(3) , 226-227.

Van Bommel, Marco, Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, Elffers, Henk, & Van Lange, Paul A.M. (2012). Be aware to care: Public self-awareness leads to a reversal of the bystander effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48 (4), 926-930.

Further information

Latané, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin , 89, 308 –324.

BBC Radio 4 Case Study: Kitty Genovese

Piliavin Subway Study

- Anxiety Disorder

- Bipolar Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Social Anxiety

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

News & Events

- Mental Health News

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

Understanding the Bystander Effect

Picture this: You’re walking down the street when you hear someone call for help. They’re being assaulted. What do you do? Most of us would like to think that we’d intervene — or at the very least, call 911. But the truth is, this isn’t what always happens.

On October 17, 2021, a woman was sexually assaulted on a train near Philadelphia, in full view of several passengers. Yet not a single one of them helped her or called the authorities, even though it was very obvious what was happening.

Onlookers time and again have withheld help to someone in need. Psychologists call this the bystander effect.

What is the bystander effect?

In short, the bystander effect is the name given to the phenomenon where people in a group fail to offer help to someone during an emergency, even though they are witnesses to the event.

In fact, research from 2014 suggests that the bigger the group, the less likely it is that anyone will come to help.

What started the research

In 1964 , a woman named Catherine “Kitty” Genovese was attacked and repeatedly stabbed by a serial killer named Winston Moseley, despite calling out for help in her apartment courtyard. As many as 38 people were said to have witnessed her being murdered.

The press coverage at the time alleged that none of these witnesses came to her aid. These sensationalized early accounts have since been disproven — but nevertheless, the case jump-started psychological research into the bystander effect.

This includes some groundbreaking research by John Darley and Bibb Latané.

How psychology explains the bystander effect

In a series of experiments, Darley and Latané found that people tend to feel a moral responsibility to help someone in distress if they believe they are the only witnesses. But if they’re surrounded by others, they’re significantly less likely to feel like they have to intervene.

In fact, in 1969, Latané found that while 70% of people would help a woman in distress if they were the only bystander, only 40% would come to her aid if other people were present.

More recently, studies have found that people are less likely to speak up if they witness cyberbullying that takes place in larger online group forums, according to a 2015 review .

Examples of the bystander effect

- ignoring bullying or cyberbullying

- filming an assault instead of calling 911

- assuming someone else will help

- walking past a person lying on the street (Content warning: graphic)

- apathy toward climate change

Why does it happen?

Researchers think that there are two group dynamics at work in the bystander effect, which is why we’re less likely to act when we’re surrounded by others.

Diffusion of responsibility

In a group, we can feel less individual responsibility to help others. This has been observed in children as young as 5 and adults alike, per 2015 research and 2017 research respectively.

It happens for a simple reason: When we’re in a group, it’s easier to assume that someone else will step up and do something, so we don’t do anything ourselves. This leads to the bystander effect. The problem is, when everyone assumes that someone else will act, no one actually does.

Social referencing

When we’re in a group, we can look to others to decide what is appropriate behavior and what’s not.

So if there is a crisis — and it’s not clear what we should do because of the confusion — we often look at what everyone else is doing to get social cues.

If we don’t see anyone doing anything, we might assume there’s a reason for the inaction and draw a false conclusion that no action is needed, according to older research by Latané and Darley.

For example, if two people are arguing but no one else seems to care, we might figure it’s just a quarrel and keep walking — even if that argument turns physical.

What makes bystanders more likely to intervene?

Some research from 2011 indicated that increased levels of danger could push bystanders to intervene.

Why? Well first of all, if the situation is dangerous to you and the victim, you’re more likely to pay attention to what’s going on. And second, in a dangerous situation, being in a group might help you feel more empowered and like you can actually help, per 2013 research .

For example, if you see someone attacking another person with a knife and you’re alone, you might be tempted to run away rather than help. But if you’re with a group, you might be more confident that you — and the group as a whole — can stop the knife-wielder if you work together.

How to counteract bystander apathy

Here are some theories on how to wake from the bystander effect:

Know what to do

If you’re an onlooker, you’re more likely to feel empowered to intervene if you know strategies to do so safely . Depending on the situation you encounter, you can choose to:

- intervene directly

- distract the attacker, if there is one

- delegate (bring in others to help)

- delay (offer follow-up resources and emotional support to the affected)

You can also take steps to be more prepared for emergencies, like taking first aid classes or getting CPR training.

Use the bystander effect positively

Some psychologists believe that simply being aware of the bystander effect could make us all more likely to react.

After all — if we know it can happen, we might be more determined to make sure we aren’t the ones that stood by and let something horrible occur.

Shame and guilt can be powerful motivators, so being observed in a group might make you feel like you have to help.

Other research from 2018 has suggested that the more we see or hear about people helping others (like donating blood), the more likely we are to do good ourselves.

Call out to a specific person

According to a 2018 research review , studies have found that people are more likely to help people they already know. This is why people are less likely to come to the aid of a stranger.

So, psychologist and professor Ken Brown said in a 2015 TEDx talk , if you’re in a crisis and you need help from others, try to focus on getting just one person to help. You’re more likely to get help, 2015 research says, if you’re direct and personal.

For example, you can call out to a specific bystander in the crowd, identifying them by the color of their shirt or hair, and ask them to call 911.

In fact, Brown recently commented to Psych Central about his 2015 TED Talks, noting the power of “asking for help in ways that reduce uncertainty.” You might’ve noticed that the audience member whom he called out of the crowd to ask for help stayed and assisted him for an unusually long period of time.

Brown reflects, “She continued to help me, despite the discomfort of standing, because I had made a direct request of her and once she started, it was clear that I wanted her to keep doing it,” until he eventually thanked her in front of the audience (but after the recording stops).

Let’s recap

The bystander effect happens more than we’d like, but there are some things we can all do to overcome it and help others — and it all starts with knowing that this phenomenon even exists.

18 sources collapsed

- Aakvaag HF, et al. (2014). Shame and guilt in the aftermath of terror: The Utøya island study. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jts.21957

- A new look at the killing of Kitty Genovese: The science of false confessions. (2017). https://www.psychologicalscience.org/publications/observer/obsonline/a-new-look-at-the-killing-of-kitty-genovese-the-science-of-false-confessions.html

- Beyer F, et al. (2017). Beyond self-serving bias: Diffusion of responsibility reduces sense of agency and outcome monitoring. https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/12/1/138/2628052

- Brown K. (2021). Personal interview.

- Bystander effect. (n.d.) https://dictionary.apa.org/bystander-effect

- Bystander intervention. (n.d.) https://www.rockefeller.edu/education-and-training/bystander-intervention/

- Cieciura J. (2016). A summary of the bystander effect: Historical development and relevance in the digital age. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1493/a-summary-of-the-bystander-effect-historical-development-and-relevance-in-the-digital-age

- Darley JM, et al. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. https://doi.apa.org/record/1968-08862-001?doi=1

- Fischer P, et al. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21534650/

- Fischer P, et al. (2013). The positive bystander effect: Passive bystanders increase helping in situations with high expected negative consequences for the helper. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23421000/

- Hortensius R, et al. (2018). From empathy to apathy: The bystander effect revisited. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0963721417749653

- Kassin SM. (2017). The killing of Kitty Genovese: What else does this case tell us? https://web.williams.edu/Psychology/Faculty/Kassin/files/Kassin%20(2017)%20-%20Kitty%20Genovese.pdf

- Latané B, et al. (1969). A lady in distress: Inhibiting effects of friends and strangers on bystander intervention. https://www.omerdank-strategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/A_lady_in_distress_Inhibiting_effects_of.pdf

- Machackova H, et al. (2015). Brief report: The bystander effect in cyberbullying incidents. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140197115001049

- Obermaier M, et al. (2014). Bystanding or standing by? How the number of bystanders affects the intention to intervene in cyberbullying. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444814563519

- Plötner M, et al. (2015). Young children show the bystander effect in helping situations. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797615569579

- Raihani NJ, et al. (2015). Why humans might help strangers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00039/full

- Studte S, et al. (2018). Blood donors and their changing engagement in other prosocial behaviors. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/trf.15085

Read this next

We're unpacking the exchange theory and breaking down what you're really attracted to in your friendships or romantic relationships.

Albert Bandura's social learning theory talks about modeling and positive reinforcement. How can it explain behaviors and mental health conditions?

You're hungry, you eat. You're thirsty, you drink. The drive reduction theory has an equation that explains these behaviors. But, what about the rest?

Feeling love for your parents is natural, but according to Freud's theory, it may be a sign of Oedipus complex if those feelings stray into…

The psychology behind conspiracy theories offers explanations of why some people are more likely to believe conspiracy theories, even those that feel…

Take the first step in feeling better. You can get psychological help by finding a mental health counselor. Browse our online resources and find a…

If you’re experiencing anxiety, these 15 essential oils may help ease your symptoms.

Here's how to encourage leadership to create a more empathetic workplace if employees feel their needs aren't met.

Research indicates that some vitamin deficiencies may put you at a greater risk of depression. Here are nine deficiencies linked to depression.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Psychology Explains the Bystander Effect

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

How the Bystander Effect Works

- Real-Life Example

- Explanations

What Is the Meaning of Bystander Effect?

The bystander effect, also known as bystander apathy, refers to a phenomenon in which the greater the number of people there are present, the less likely people are to help a person in distress.

If you witnessed an emergency happening right before your eyes, you would certainly take some sort of action to help the person in trouble, right? While we might all like to believe that this is true, psychologists suggest that whether or not you intervene might depend upon the number of other witnesses present.

When an emergency situation occurs, the bystander effects holds that observers are more likely to take action if there are few or no other witnesses.

Being part of a large crowd makes it so no single person has to take responsibility for an action (or inaction).

In a series of classic studies, researchers Bibb Latané and John Darley found that the amount of time it takes the participant to take action and seek help varies depending on how many other observers are in the room. In one experiment , subjects were placed in one of three treatment conditions: alone in a room, with two other participants, or with two confederates who pretended to be normal participants.

As the participants sat filling out questionnaires, smoke began to fill the room. When participants were alone, 75% reported the smoke to the experimenters. In contrast, just 38% of participants in a room with two other people reported the smoke. In the final group, the two confederates in the experiment noted the smoke and then ignored it, which resulted in only 10% of the participants reporting the smoke.

Additional experiments by Latané and Rodin (1969) found that 70% of people would help a woman in distress when they were the only witness. But only about 40% offered assistance when other people were also present.

What Is a Real-Life Example of the Bystander Effect?

The most frequently cited example of the bystander effect in introductory psychology textbooks is the brutal murder of a young woman named Catherine "Kitty" Genovese. On Friday, March 13, 1964, 28-year-old Genovese was returning home from work. As she approached her apartment entrance, she was attacked and stabbed by a man later identified as Winston Moseley.

Despite Genovese’s repeated calls for help, none of the dozen or so people in the nearby apartment building who heard her cries called the police to report the incident. The attack first began at 3:20 AM, but it was not until 3:50 AM that someone first contacted police.

An initial article in the New York Times sensationalized the case and reported a number of factual inaccuracies. An article in the September 2007 issue of American Psychologist concluded that the story is largely misrepresented mostly due to the inaccuracies repeatedly published in newspaper articles and psychology textbooks.

While Genovese's case has been subject to numerous misrepresentations and inaccuracies, there have been numerous other cases reported in recent years. The bystander effect can clearly have a powerful impact on social behavior, but why exactly does it happen? Why don't we help when we are part of a crowd?

Why Does It Happen?

There are two major factors that contribute to the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility .

Because there are other observers, individuals do not feel as much pressure to take action. The responsibility to act is thought to be shared among all of those present.

The second reason is the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways. When other observers fail to react, individuals often take this as a signal that a response is not needed or not appropriate.

Researchers have found that onlookers are less likely to intervene if the situation is ambiguous. In the case of Kitty Genovese, many of the 38 witnesses reported that they believed that they were witnessing a "lover's quarrel," and did not realize that the young woman was actually being murdered.

A crisis is often chaotic and the situation is not always crystal clear. Onlookers might wonder exactly what is happening. During such moments, people often look to others in the group to determine what is appropriate. When they see that no one else is reacting, it sends a signal that perhaps no action is needed.

Preventing the Bystander Effect

What can you do to overcome the bystander effect ? Some psychologists suggest that simply being aware of this tendency is perhaps the greatest way to break the cycle. When faced with a situation that requires action, understand how the bystander effect might be holding you back and consciously take steps to overcome it. However, this does not mean you should place yourself in danger.

But what if you are the person in need of assistance? How can you inspire people to lend a hand? One often recommended tactic is to single out one person from the crowd. Make eye contact and ask that individual specifically for help. By personalizing and individualizing your request, it becomes much harder for people to turn you down.

Manning R, Levine M, Collins A. The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: the parable of the 38 witnesses . Am Psychol. 2007;62(6):555-62. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.6.555

Darley JM, Latané B. Bystander “apathy.” American Scientist. 1969;57:244-268.

Latané B, Darley JM. The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? Prentice Hall, 1970.

Solomon LZ, Solomon H, Stone R. Helping as a function of number of bystanders and ambiguity of emergency . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 1978;4(2):318-321. doi:10.1177/014616727800400231

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Bystander Responses to a Violent Incident in an Immersive Virtual Environment

Aitor rovira, richard southern, david swapp, jian j zhang, claire campbell, mark levine.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

* E-mail: [email protected]

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Conceived and designed the experiments: MS ML. Performed the experiments: AR DS RS. Analyzed the data: MS. Wrote the paper: MS ML AR RS DS JJZ CC. Computer animation: RS JJZ.

Received 2012 Mar 1; Accepted 2012 Nov 22; Collection date 2013.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.

Under what conditions will a bystander intervene to try to stop a violent attack by one person on another? It is generally believed that the greater the size of the crowd of bystanders, the less the chance that any of them will intervene. A complementary model is that social identity is critical as an explanatory variable. For example, when the bystander shares common social identity with the victim the probability of intervention is enhanced, other things being equal. However, it is generally not possible to study such hypotheses experimentally for practical and ethical reasons. Here we show that an experiment that depicts a violent incident at life-size in immersive virtual reality lends support to the social identity explanation. 40 male supporters of Arsenal Football Club in England were recruited for a two-factor between-groups experiment: the victim was either an Arsenal supporter or not (in-group/out-group), and looked towards the participant for help or not during the confrontation. The response variables were the numbers of verbal and physical interventions by the participant during the violent argument. The number of physical interventions had a significantly greater mean in the in-group condition compared to the out-group. The more that participants perceived that the Victim was looking to them for help the greater the number of interventions in the in-group but not in the out-group. These results are supported by standard statistical analysis of variance, with more detailed findings obtained by a symbolic regression procedure based on genetic programming. Verbal interventions made during their experience, and analysis of post-experiment interview data suggest that in-group members were more prone to confrontational intervention compared to the out-group who were more prone to make statements to try to diffuse the situation.

Introduction

A violent and unprovoked attack by one person on another unfolds in close view of an unrelated bystander: under what conditions will the bystander be likely to intervene to help the victim? In this paper we address the hypothesis that group affiliation between the bystander and the victim provides a powerful incentive for the bystander to try to intervene to stop the attack, or prevent harm to the victim, and in particular that this operates even though the perpetrator and victim are virtual human characters. Our experiment involved fans of an English football team, Arsenal. In one experimental condition (in-group) the fan conversed with a virtual character that was clearly an Arsenal supporter and in another condition the character was just a general football enthusiast but not an Arsenal fan (out-group). The virtual character was later threatened by a perpetrator that, in the in-group condition, specifically attacked his Arsenal affiliation. Our expectation was that based on group affiliation, those in the in-group would intervene more than those in the out-group. First we place this in the general context of studies of bystander intervention, and then describe the detailed design of the experiment and the results.

Research on the behaviour of bystanders in emergencies began with the response to the rape and murder of Kitty Genovese in New York in 1964. Social psychologists Bibb Latane and John Darley read a report on the murder in the New York Times suggesting that 38 witnesses had watched the murder unfold over 30 minutes from their apartment windows– and yet failed to intervene. In order to understand why this might have happened, they set out to create laboratory based experimental analogies of the event. They set up carefully choreographed situations in which bystanders were faced with a non-violent emergency situation while on their own or in the presence of others [1] , [2] . The research led to the discovery of the ‘bystander effect’ – the idea that people are more likely to intervene on their own than in the presence of others [1] . This is one of the most reliable and robust findings in social psychology [3] , [4] .

However, as Cherry pointed out [5] , through translating the events surrounding the Genovese murder into laboratory settings, Latane and Darley neglected some of the key features of the event. Despite the fact that the original murder involved violence by a man against a woman, subsequent experimental analogies tended to remove both the gendered nature of the attack and the violence. Although there are thousands of studies using non-violent emergency settings, it is possible to find only a few experiments that did retain violence as the emergency variable [6] , [7] , [8] , [9] , [10] . These found results that were at odds with the traditional bystander paradigm. In violent emergencies, what seemed to be most important about the likelihood of bystander intervention was not the presence of others, but rather the bystanders’ beliefs about the nature of the relationship between perpetrator and victim [9] , [10] . In an experiment that did vary the number of bystanders to a violent emergency Harari et al. [6] showed that the presence of others actually enhanced the likelihood of bystander intervention in a simulated rape situation. This finding has been supported by contemporary work which presents violence to participants by means of a CCTV video link, where the presence of others is not found to inhibit helping [11] and can sometimes enhance it [12] . A recent meta-analysis by Fisher and colleagues [4] confirms that intervention behaviour in violent emergencies does not fit the traditional bystander effect explanation.

If violent emergencies are different in some way, it is important to understand the processes at work. Almost all violence research shares a similar limitation. In order to circumvent the practical and ethical problems of presenting violence in experimental settings, these experiments tend to avoid placing participants in direct contact with the violence itself. The only exception is the work described in [10] in which a role-play setting was used, and confederates actually staged a violent confrontation in front of naive participants who were also taking part in the role-play game. However, it is highly unlikely that contemporary ethics boards would allow this kind of design. The other studies either have the violence happening at a distance where it is possible to avoid the event [6] or present the violence as happening contemporaneously but where it can only be heard [7] , [8] , [9] , or happening in another room where it can be seen on CCTV link [11] . This distancing of participants from the violence is required to satisfy the ethical and practical difficulties of experimental design, but may itself introduce psychological effects that interfere with the veridical nature of the situation. Imagining the violence, or having it happen in another room, is not the same as being physically where the violence erupts.

In [13] we argued that the use of immersive virtual environments (IVE) goes some way towards solving this problem, since there is mounting evidence that when people are faced with events and situations in an IVE they tend to behave and respond as if these were real [14] . IVEs portray a simulated computer generated reality at life size that is sensorially surrounding. Participants perceive this world through wide field-of-view stereo vision and sound. The form of perception involves more or less natural sensorimotor contingencies - meaning that the whole body is used for perception much as in physical reality, based at least on head-gaze direction and orientation achieved through head-tracking. This gives rise to the sensation of being in the virtual place that is depicted, a place-illusion. Additionally when there are dynamically unfolding events in the environment that personally refer to the participant, and where actions of the participant apparently cause responses in the virtual environment, this gives rise to a plausibility-illusion, meaning that events have the illusory quality of being real. When the participant has the double illusion - of being in the virtual place and where events that are happening are apparently really happening, this can give rise to behaviour and responses that are appropriate to the situation as if it were playing out in reality [15] .

IVEs provide therefore a powerful tool for experimental studies in social psychology [16] and classic effects such as proxemics [17] where distances that people maintain between themselves are governed by social norms, have been reproduced several times in IVEs with respect to virtual humanoid characters [18] , [19] , [20] . Moreover, IVEs have been useful for experiments that would otherwise be difficult to carry out in any other way, such as the study of male risk taking in the presence of observers, specifically the differential effects of the observers being male or female [21] .

Closer to the present study which focuses on responses to violence, the Stanley Milgram obedience paradigm [22] has been reproduced with IVE avoiding the ethical difficulties of deception [23] , [24] . IVEs provide environments completely under control of a computer program but where people respond realistically. Every experimental condition can be exactly reproduced across trials as needed, and hence can be used for laboratory based experiments.

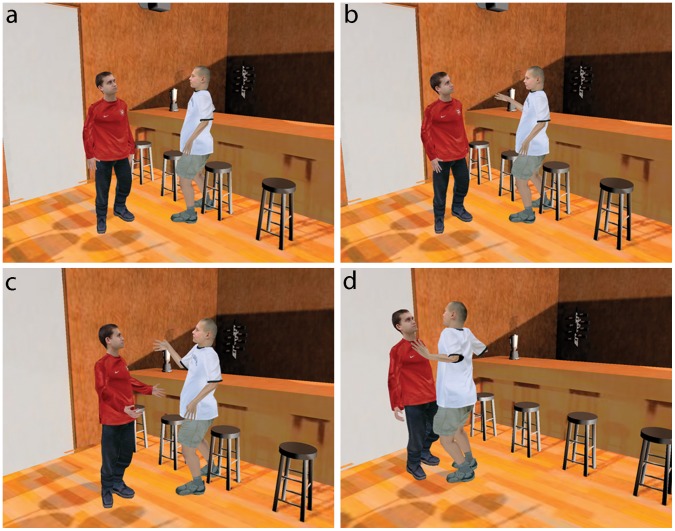

It has been argued before that IVEs provide an excellent tool for the study of prosocial behaviour [25] . The experiment described in the present study is specifically concerned with the likelihood of prosocial behaviour when participants are placed in direct proximity to violent behaviour. We explore the hypothesis that the psychological relationships between bystanders and the others involved are important in bystander behaviour, in this case specifically the relationship between the bystander and the victim [12] , [26] , [27] , [28] . The experimental conditions provide a context where it is certain that the violence between perpetrator and victim is of the same magnitude and intensity for each experimental trial. Participants (n = 40) all supporters of the Arsenal Football Club , entered into a virtual reality that represents a bar. A male virtual human (V) approached and conversed with them about football for a few minutes. In one condition V wore an Arsenal football shirt and spoke enthusiastically about the club (in-group condition). In a second condition V wore an unaffiliated red sports shirt, and asked questions about Arsenal without special enthusiasm, using neutral responses and displaying ambivalence about Arsenal’s prospects (out-group condition). After a few minutes of this conversation another male virtual human (P, perpetrator) who had been sitting by the bar walked over to V (victim) and started an argument that he continually escalated until it became a physical attack ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. The Victim and Perpetrator.

The Victim (V) is in the red shirt, with an Arsenal emblem in the in-group condition, and with a plain football shirt of the same colour in the out-group condition. The perpetrator (P) had been sitting by the bar. (a) P stood up to approach V and (b) started an argument. (c) As the argument progressed V made conciliatory statements and postures while (d) P became ever more aggressive finally pushing V violently against a wall.

The main response variable was the extent to which the participant attempted to intervene during this confrontation. Interventions were verbal utterances or physical moves towards the two virtual characters and were coded from video recordings by two independent researchers (Methods). There were two binary factors group and LookAt . Group was whether V was in-group (Arsenal supporter) or out-group with respect to the participant. LookAt was whether or not occasionally during the confrontation V would look towards the participant or not ( LookAt = ‘on’ or ‘off’). The experiment used a between-groups design, with n = 40, 10 participants allocated arbitrarily to one of the four cells of the 2×2 design. The degree of support for the Arsenal club was similar between the 4 experimental conditions ( Text S1 ). At the end of their session they answered a questionnaire, and this was followed by an interview and debriefing. The data from two participants could not be used due to video recording failures.

Numbers of Interventions

Table 1 shows the means and standard errors of the numbers of interventions indicating that the mean number of interventions was higher for the in-group than the out-group, but that the LookAt factor had no effect. Two-way analysis of variance was carried out on the response variables, the number of physical ( nPhys ) and number of verbal ( nVerbal ) interventions. ANOVA for nPhys indicates that the mean is greater for the in-group than for the out-group condition (P = 0.02) but with no significant differences for the LookAt factor and no interaction effect. However, the residual errors of the fit were strongly non-normal (Shapiro-Wilk test P = 0.0008). To overcome this problem a square root transformation was applied to nPhys . This resulted in the same conclusions for group (P = 0.016, partial η 2 = 0.15) and no significance for LookAt (P = 0.297, partial η 2 = 0.03). The normality of the residuals is improved although not ideal (Shapiro-Wilk P = 0.034). For the response variable nVerbal the results were similar: ANOVA of nVerbal on group and LookAt shows no significant interaction term, group has significance level P = 0.095, and for LookAt P = 0.228. However, again the residual errors are far from normal (SW P = 0.0008). The square root transformation gives P = 0.060, partial η 2 = 0.10 for group and P = 0.112, partial η 2 = 0.07 for LookAt . The residual errors are compatible with normality (SW P = 0.24).

Table 1. Means and Standard Errors of Numbers of Interventions.

n = 9 for each of the two Out-group cells, n = 10 for each of the two In-group cells, n = 38 in total.

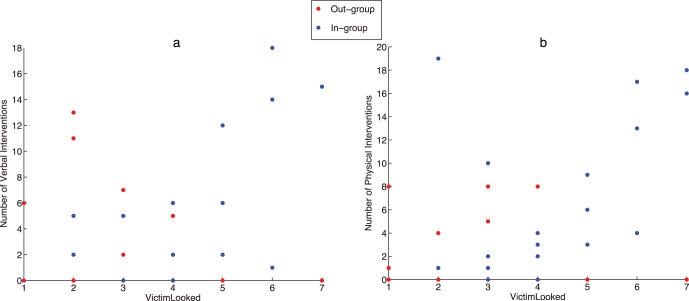

The factor LookAt represents whether the V avatar was programmed to occasionally look toward the participants. Additionally, the post experience questionnaire included the statement ( VictimLooked ) “After the argument started, the victim looked at me wanting help” which was scored on a scale from 1 (least agreement) to 7 (most agreement). VictimLooked therefore represents the belief of the participants as to whether the victim looked towards them for help . There is no significant difference between the mean VictimLooked score of those who were in the group LookAt = ‘on’ (mean 3.3, SD = 1.8, n = 20) and those in the group LookAt = ‘off’ (mean 4.0, SD = 1.5, n = 20) (P = 0.12, Mann-Whitney U). Hence the response to this question was not based on the number of actual looks of the victim towards the participant, and therefore was a belief. It turns out that VictimLooked plays a significant role in the number of interventions.

Figure 2 shows the scatter plots of nPhys and nVerbal on the questionnaire response VictimLooked for the out-group and in-group. These reveal a quite different relationship in the two cases. In the case of the in-group there is a positive association between the number of interventions (verbal or physical) and the perception that the victim was looking towards the participant for help. In the case of the out-group there appears to be no relationship in the nPhys case and a possible negative relationship in the nVerbal case. Using the same strategy as above in order to obtain residual errors compatible with normality, ANCOVA of nPhys 0.5 on group with VictimLooked as a covariate shows that the slopes of the regression line are different between the in-group and out-group (P = 0.004, partial η 2 = 0.22 for the slopes, SW P = 0.18). For the number of verbal interventions, using nVerbal 0.5 the difference in slopes between in-group and out-group is significant at P = 0.004 (partial η 2 = 0.22 for the slope, SW P = 0.12).

Figure 2. Number of interventions by VictimLooked and Group .

(a) For the verbal interventions and (b) for the physical interventions.

These results indicate that the response to the belief that the victim was looking towards the bystander for help was different between the in-group and out-group. For those in the in-group condition the greater their belief that the victim was looking to them for help the greater the number of verbal and physical interventions. For those in the out-group condition there is no such association. These results are further corroborated using multivariate analysis of variance on the response vector ( nPhys 0.5 , nVerbal 0.5 ) ( Text S2 ).

Numbers of Interventions - Symbolic Regression

The previous section provided standard analyses for these types of data. Even though this revealed positive results consistent with our initial hypothesis, in this section we also employ a quite different method using symbolic regression, to throw further light on the experimental results. The purpose is to consider the relationship between the number of interventions, and the experimental factors, but now also including any possible influence of the subjective variables as elicited through the post-experience questionnaire ( Table 2 ). Standard statistical analysis is based, amongst other things, on the assumption of linearity in the parameters. But in such a complex situation as the one under consideration, on what grounds is such an assumption valid when considering the multivariate influence of a number of factors potentially influencing bystander intervention? Symbolic regression does not rely on such linearity, being a method for discovering relationships between variables using the technique of genetic programming [29] ( Text S3 ). It has recently been shown to be able to discover complex physical laws automatically [30] , using a program called Eureqa, which was used in the analysis presented below. In the context that we apply this technique here, we consider it as a data reduction method. It allows us to succinctly represent the original data but with quite simple equations while preserving the variance in the original data. It is not a technique that can be compared with statistical significance testing, it is rather a data exploration method, that can lead to understanding of complex data, where models generated by this technique can be used for hypothesis formation in later experimental study.

Table 2. The Post-Questionnaire and Corresponding Variable Names.

All items were presented as statements on a 1–7 Likert scale where 1 meant least agreement and 7 most agreement with the corresponding statement.

The operators that were used for the symbolic regression were: Constant, +, −, ×, /, sqrt, exp, log. The program was run for both nPhys and nVerbal . The population size (number of formulae per generation) was chosen by Eureqa as 2560. For each analysis the program was run on a 40 core cluster (see Methods) and left running for many hours until the solution set of equations stabilized. The fitness metric used was mean absolute error.

We consider first nPhys . The Eureqa program was left to run for more than 2000 core hours. It reported 28 equations. Each has an associated size parameter that represents the complexity of the equation (ranging from 1, least, to 53, most complex), a fitness value, the square of the correlation coefficient between the response variable and the fitted values from the equation, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The AIC is an information theoretic measure of the relative goodness of fit of a model to the data. Smaller AIC values represent better goodness of fit, taking also into account the complexity of the model. The AIC is often used in model selection procedures, as discussed extensively in [31] .

The model with the smallest AICs is shown in Eq (1). Here group is 0 for out-group and 1 for in-group. Similarly LookAt is 0 for ‘off’, and 1 for ‘on’. The other variables are from the questionnaire ( Table 2 ).

(R 2 = 0.85, AIC = 108, Size = 26).

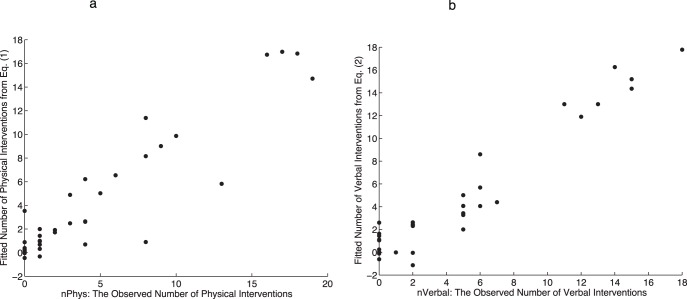

Figure 3a shows the relationship between the observed and fitted number of interventions based on Eq (1) (the diagram is very similar for all the top fitting equations generated). The high fitting equations all, of course, give similar results and Eq (1) is marginally preferred since it has high explanatory power (in terms of correlation) and the smallest AIC, and on the range of complexity of the models produced is about half way along the scale amongst all generated equations.

Figure 3. The fitted number of interventions by VictimLooked from Eqs.

(1) and (2). (a) The fitted against observed values for nPhys . (b) The fitted against observed for nVerbal .

The equation shows a clear distinction between in-group and out-group. For the out-group (group = 0) the entire first term, on the left-hand side of the plus sign, vanishes (20 of the 28 equations generated have this exponential term). For the in-group (group = 1), it can be seen that LookAt has a very small but positive influence on the number of interventions but VictimLooked has a greater influence. As it ranges from 1 to 7 the number of interventions increases by 0.015*exp( VictimLooked ), which is, for example, 2 for VictimLooked = 5, and 16 for VictimLooked = 7, other things being equal.

The second term only includes a few of the questionnaire variables. Examining this term, the number of interventions is proportional to concern about the safety of others, and the feeling that the fight should be stopped. It is inversely proportional to the feeling of wanting to get out, and the fear that other people might turn up to make things worse.

Now we turn to the number of verbal interventions nVerbal , and follow the same analysis. Here the genetic program ran for 1930 core hours. 28 equations were produced with size complexity ranging from 1 to 71. The equation with the lowest AIC is shown in Eq (2).

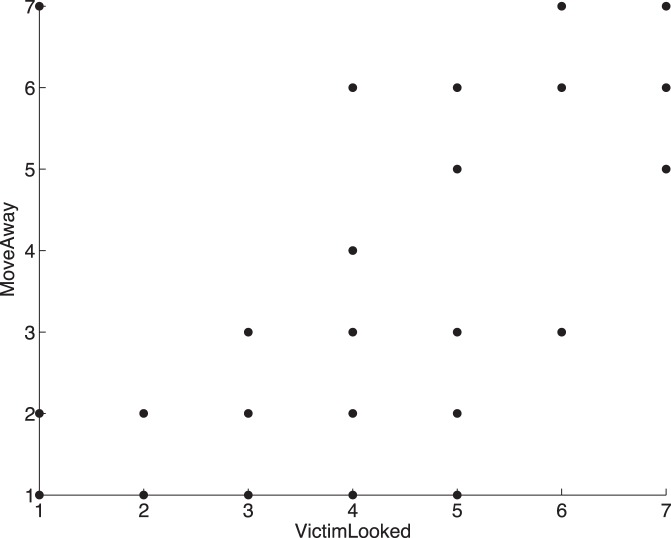

(R 2 = 0.93, AIC = 83, Size = 29).

As before all the high fitting equations give very similar results and we take Eq. (2) as representative. Figure 3b shows the plot of fitted by observed values over the data set for Eq. (2). Examining the equation we see this time there is no effect of group . The number of verbal interventions is proportional to the feeling of the need to stop the fight, and inversely proportional to the fear that other people might arrive and make things worse. Also there is a positive association with participant fears for their own safety. The most interesting variable again is VictimLooked , the belief that the V avatar was looking towards the participant for help. The variable MoveAway is strongly related with VictimLooked which must be taken into account otherwise the equations explode into huge values as VictimLooked increases. Figure 4 shows that there is a very strong positive correlation between these two variables (apart from 1 outlier) (r = 0.71, P = 3.3×10 −7 ), with regression line MoveAway = −0.38+0.82 VictimLooked . Moreover 22 out of the 28 equations include the exponential term involving these two variables. We maintain this relationship when examining the effect of VictimLooked on nVerbal rather than fixing MoveAway at a constant value, and taking this into account high values of VictimLooked are associated with a larger number of interventions.

Figure 4. Scatter diagram of MoveAway against VictimLooked .

Note the one outlying point when VictimLooked = 1 and MoveAway = 7.

The Interviews

After the experimental trial there was a short interview with the participants, followed by their debriefing where the purposes of the experiment were explained. The interviews concentrated on several main questions: their feelings and responses during their experience, the extent to which they judged their responses to be realistic, factors that might have increased their intervention, and factors that drew them out of the experience. Summaries of the interviews were coded into key codes and frequency tables constructed, using the HyperResearch software [32] .

We consider first the responses and feelings of participants during their experience. Table 3 shows the codes and two example sentences of each code and Table 4 the code frequencies.

Table 3. Codes for the Interview Questions: What feelings/responses did you have while this was happening?

Table 4. frequencies of the codes in table 3 ..

The impression from the interviews as shown in Table 4 is that those in the out-group tended to sympathize with or feel sorry for V. Also many of them wanted to just leave the situation, felt uninvolved, or a few found the situation silly. For those in the in-group it seems to be more anger and frustration that could be the driving force of their intervention, and their response was more likely to be a confrontational one. None of them felt uninvolved, found the situation funny or silly, felt sorry for V or wanted to leave. Some of the in-group expressed surprise at their own responses even though they were aware that it was virtual reality, whereas none of the out-group expressed such surprise. This fits with the fact that many of the out-group felt uninvolved and none of the in-group felt so.

Tables 5 and 6 give the results for the interview question regarding the authenticity of response in comparison with reality. We do not show the separate tables for in-group and out-group since there is no difference between them in this regard, although there is some suggestion of a difference between the LookAt groups. It seems that those in the LookAt ‘off’ group were more likely to remark on the lack of interaction, and to contrast their behaviour in virtual reality and reality. They were less likely to report their responses as being realistic. In the combined sample just over half found that their responses were realistic.

Table 5. Codes for the Interview Question: Were your responses realistic?

Table 6. frequencies of the codes in table 5 ..