- Open access

- Published: 10 March 2021

Measuring health inequalities: a systematic review of widely used indicators and topics

- Sergi Albert-Ballestar 1 , 2 &

- Anna García-Altés ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3889-5375 1 , 2 , 3

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 20 , Article number: 73 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

17 Citations

36 Altmetric

Metrics details

According to many conceptual frameworks, the first step in the monitoring cycle of health inequalities is the selection of relevant topics and indicators. However, some difficulties may arise during this selection process due to a high variety of contextual factors that may influence this step. In order to help accomplish this task successfully, a comprehensive review of the most common topics and indicators for measuring and monitoring health inequalities in countries/regions with similar socioeconomic and political status as Catalonia was performed.

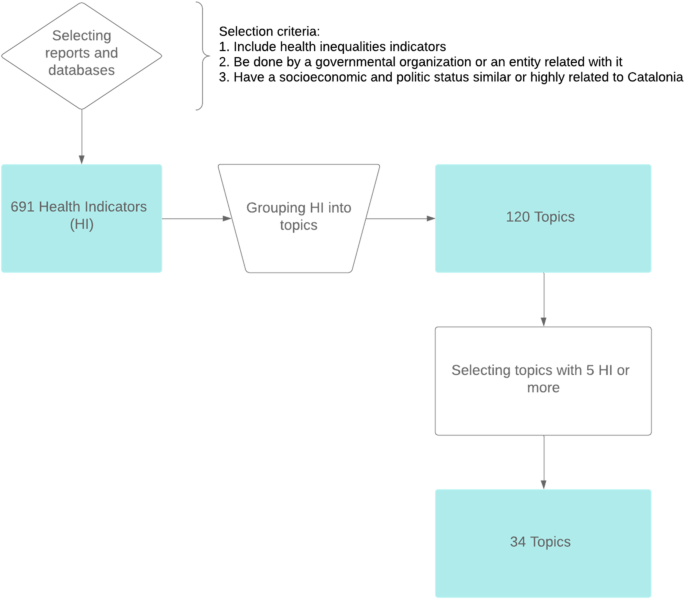

We describe the processes and criteria used for selecting health indicators from reports, studies, and databases focusing on health inequalities. We also describe how they were grouped into well-known health topics. The topics were filtered and ranked by the number of indicators they accounted for.

We found 691 indicators used in the study of health inequalities. The indicators were grouped into 120 topics, 34 of which were selected for having five indicators or more. Most commonly found topics in the list include “Life expectancy”, “Infant mortality”, “Obesity and overweight (BMI)”, “Mortality rate”, “Regular smokers/tobacco consumption”, “Self-perceived health”, “Unemployment”, “Mental well-being”, “Cardiovascular disease/hypertension”, “Socioeconomic status (SES)/material deprivation”.

Conclusions

A wide variety of indicators and topics for the study of health inequalities exist across different countries and organisations, although there are some clear commonalities. Reviewing the use of health indicators is a key step to know the current state of the study of health inequalities and may show how to lead the way in understanding how to overcome them.

Introduction

Strong efforts to tackle health inequalities can be seen at international and national level since the 1980s. In early 2008, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Commission on Social Determinants of Health called for action on the social determinants of health, the conditions in which persons are born, grow, work, live, and age, to “close the gap in a generation” [ 1 ]. In late 2008, the Spanish Public Health General Direction ( Dirección General de Salud Pública) and the Foreign Health of Health Ministry and Social Policy ( Sanidad Exterior del Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social ) requested the constitution of the Commission for the Reduction of Social and Health Inequalities ( Comisión para Reducir las Desigualdades Sociales en Salud en España (CRDSS-E) [ 2 ]. The mission of CRDSS-E was to elaborate on a proposal of intervention measures to reduce health inequalities. The CRDSS-E published two documents: one analysing health inequalities in the Spanish context [ 3 ], and another describing some policy proposals to tackle them [ 4 ]. In 2011, a total of 125 countries, Spain being one of them, developed and signed the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health [ 5 ]. The declaration recommended interventions from governments and international organisations [ 6 ].

At a regional level in Catalonia, tackling health inequalities is one of the main goals of both the Catalan Health Plan 2016–2020 (led by the Health Department of the Catalan Government) [ 7 ] and the Interdepartmental and Intersectorial Public Health Plan 2017–2020 (PINSAP) [ 8 , 9 ]. During the past years, various reports and peer-reviewed papers about the health effects of the economic crisis on the population of Catalonia were published by the Catalan Health System Observatory [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Overall, much effort has been devoted to monitoring and tackling health inequalities at regional, national, and international levels. Even so, OECD countries continue to present large disparities in health, including, for example, significant differences in life expectancy between people with the highest and lowest levels of education [ 18 ]. The selection of topics represents the first step in monitoring health inequalities according to many conceptual frameworks and is highly relevant, as these topics will potentially limit the detection of health inequalities within the population, hence playing a key role in providing evidence for posterior decision-making [ 19 , 20 ]. Yet some difficulties may arise during the selection of relevant topics, as well as their health indicators. A wide diversity of indicators for monitoring health inequalities have been used across different countries and organisations; this is due to the high variety of contextual factors that may have an influence on it, such as the study goals or the information resources available.

In order to help accomplish this task successfully, the objective of this study is to perform a systematic review of the most common topics and indicators used for measuring and monitoring health inequalities in the reports, projects, and databases of international, national, and regional governmental organizations.

The main purpose of this study is to provide a broad overview of health inequalities topics considered relevant by different public health organizations. Nevertheless, the focus of this review is on countries/regions with similar socioeconomic and political status to Catalonia. It may also be useful for other organizations who decide to study or monitor health inequalities to accomplish its very first step: topic selection. In addition, gaining some insights about which health issues are being prioritized, as well as which indicators were used, are considered secondary goals.

Material and methods

First, a bibliographic search was performed using PubMed, Google Scholar, and Google search engine with the terms “ health inequalities ”, “ health observatories ” and “ health inequalities indicators ”. Occasionally, names of concrete regions, countries, or organisations were added to these terms (i.e., “ Andalucía health observatory ” or “ Canada health inequalities ”). The search was performed from March to June of 2019. Once finished, a set of inclusion criteria was applied; studies included in the review had to:

Include health inequalities indicators : All the reports that contained no health indicators were automatically discarded (i.e., policy frameworks [ 21 ]).

Have been carried out by a governmental organisation or a related entity, whether at an international, national, or regional level : the reports not published by governmental (or government-related) organisations were discarded.

Have a socioeconomic and political status similar (or highly related) to Catalonia : some reports were discarded due to significant differences in the socioeconomic profile of the countries they were studying in comparison to Catalonia or Spain.

Once the reports were selected, the authors performed a quality control check of the indicators shown in the reports and databases. The indicators had to match the basic anatomy of an indicator as a minimum requirement to be considered an indicator. This basic anatomy consists of containing data, i.e. the numerical data input; and containing good metadata, like a title and an explanation of how an indicator is defined and calculated [ 22 ]. In addition, the different reports found were classified according to the geo-political region they were studying: 1. international, 2. national, and 3. regional (Table 1 ).

After this selection process, the indicators were grouped into topics by semantic matching of their definition as well as by the area of knowledge there are intended to measure. Most of the topics were supported by references of relevant organisations like the WHO or the United Nations (UN) (see Table 2 ). Each topic was uniquely named in accordance with the area of knowledge that instruments were intended to measure. Indicators from different sources were often merged due to high similarities between them (most commonly, the only differences were stratifiers such as age, gender or region). Every topic had to be formed by at least five indicators in order to be considered relevant enough; the topics with less than five indicators were discarded.

The search was performed by the two researchers, and the results shared in order to agree on any discrepancies. All the data was organised in spreadsheets to identify common indicators, and then sorted by the amount of indicators they included. The names of the indicators in the spreadsheets were those given in the original reports or their metadata information.

In total, 21 reports, projects, and databases were identified and classified into three categories: 1. international [ 8 ], 2. national [ 10 ], and 3. regional [ 3 ]. In the first category, international, all the projects selected were carried out or funded by the European Commission [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ], the WHO [ 28 , 29 ] or the World Bank [ 30 ]. In the following category, national, studies were conducted by health agencies or governments of countries such as Andorra [ 31 ], Australia [ 32 ], Canada [ 33 , 34 ], England [ 35 , 36 ], Scotland [ 37 ], Slovenia [ 38 ], Spain [ 39 ] or Portugal [ 40 ]. In the last category, regional, some reports published by Spanish regions were included (Andalucía [ 41 ], Barcelona [ 42 ], Valencia [ 43 ]). A total of 691 health indicators were identified (Table 1 ).

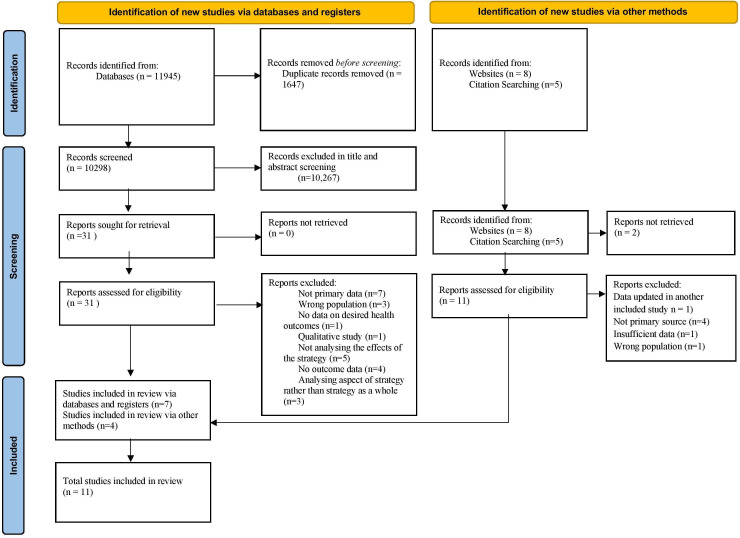

Following an iterative process of evaluation, we identified a core set of 120 candidate topics, of which 34 were finally selected (Fig. 1 ). Table 2 describes a complete list of 34 topics with the corresponding definition of each topic. The ten most commonly used were: “Life expectancy”, “Infant mortality”, “Obesity and overweight (BMI)”, “Mortality rate”, “Regular smokers/tobacco consumption”, “Self-perceived health”, “Unemployment”, “Mental well-being”, “Cardiovascular disease/hypertension”, “Socioeconomic status (SES)/material deprivation”. However, some topics that ranked below these were closely related with some of the most common topics; for example, “Perinatal, neonatal and stillbirths mortality” might be considered as a subtype of “Infant mortality”; and “Perceived mental health” is similar to both “Mental well-being” and “Self-perceived health”. Furthermore, some indicators may represent antithetically the same area of knowledge; that is the case for the indicators in the topic “Long-term limitations/chronic illnesses” and the indicator “Healthy Life Years (HLY)” [within the topic “Life expectancy”], where the former (long-term limitations or chronic illnesses) is used to determine the latter (the end of a healthy life condition). Nevertheless, the metadata of the health indicators within each topic was highly homogeneous: they all had similar definitions and methodology.

Flowchart of the processes undertaken to review the most common topics in the study of health inequalities

In general, the indicators within each topic were very similar. In fact, often the differences among them were related to the different stratifiers (such as sex, age or region) used for their calculation. For example, in the first topic “Life expectancy”, indicators have different variations: “Life expectancy at birth” [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 37 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], “Life expectancy at birth by sex” [ 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 33 , 34 ], “Life expectancy at a certain age” [ 25 , 33 , 35 , 40 ], “Life expectancy by educational attainment level” [ 25 ], and “Life expectancy at birth by socioeconomic status” [ 25 ]. Complex measures of inequality, such as “Slope index of inequality (SII) for male and female life expectancy” [ 34 ] may be considered another (more advanced) variation.

Furthermore, in the case of a health outcomes or diagnostics (such as mortality or cancer) the concrete disease or cause may also play an important role in the heterogeneity found among the health indicators. Indicators are focused on different aspects, such as prevalence and incidence, mortality, preventive measures, or treatments. For example, for the topic “HIV”: “HIV incidence” [ 23 , 26 , 28 , 33 , 40 ], “Prevalence of HIV, male/female, by ages” [ 29 , 39 ] and “AIDS-related mortality rate” [ 28 , 39 ] are the most common, yet “Antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage” [ 28 ] and “HIV test results for TB patients (positive results)” [ 28 ] can also be relevant.

The results of the study show that the most common topics are related to:

Mortality/life expectancy: “Life expectancy” [ 44 , 45 ], “Infant mortality” [ 46 ] or “Mortality rate” [ 47 ] are widely used to study health inequalities.

Incidence/mortality rates of specific diseases: “Cardiovascular disease/hypertension”, “Cancer (incidence or mortality)” [ 48 ], “Diabetes/insulin resistance” [ 49 ], “HIV” [ 50 ], “Tuberculosis (TB)” [ 51 ] or “Respiratory diseases”.

Social determinants of health [ 52 ]:

◦ “Living and working conditions” where this could be studied at an individual level, was highly ranked: “Unemployment” [ 53 ] and “Primary studies/illiteracy”. Otherwise, these indicators were at the bottom of the list.

◦ This was similar for “Individual lifestyle factors and social and community networks” topics, which can also be studied at an individual level: “Obesity and overweight (BMI)” [ 54 , 55 ], “Regular smokers/tobacco consumption” [ 56 ], “Alcohol consumption” [ 57 ], “Hazardous alcohol consumption”, “Physical activity” [ 58 ], and “Food consumption (vegetables, fruit, salt)”.

◦ Socioeconomic level: “Socioeconomic status (SES)/material deprivation” [ 59 , 60 ].

◦ Healthcare system: “Healthcare resources” and “Policy and Legislation”.

Main results of the study

The results of the study showed that the most common topics were related to mortality/life expectancy, incidence/mortality rates of specific diseases (i.e., TB or HIV), and social determinants of health, such as living and working conditions, and individual lifestyle factors and social and community networks, according to Dahlgren and Whitehead’s model of the social determinants of health [ 52 ]. The indicators that can be studied at an individual level tended to be highly ranked, in comparison to those that are studied at different levels (such as hospital or region), which tended to be at the bottom. Many methodological differences between indicators were due to stratifiers in their calculation.

Study selection criteria

To include health inequalities indicators was a fundamental requirement for any report in order to be included in the review. Hence, although some reports provided in-depth insights about tackling health inequalities (i.e., [ 21 , 61 ]) they were not selected due to lack of health indicators monitoring.

In addition, to be carried out by a governmental or a government-related organisation was also an important requirement, as many academic and/or private institutions carry out studies and reviews of health inequalities, but their policy-making influence is limited. Their reports tend to be focused on concrete knowledge fields, such as gender influence [ 62 ], the effects of economic crises [ 63 ], or access to healthcare [ 64 ]; which are also relevant for the study of health inequalities but whose authorship does not fit the selection criteria, as the main interest of this paper is identifying the health inequalities indicators used by health agencies or similar government-related entities. The reports not produced by this kind of organisation were rejected.

Lastly, to have a socioeconomic and politic status similar or highly related to Catalonia criteria was intended to exclude reports whose health indicators were adapted to least developed/developing countries where, for example, access to treatments of diarrhea for infants may still be an issue [ 65 ]. Hence, some reports were discarded due to significant differences in the socioeconomic profile of the countries they are studying in comparison to Catalonia or Spain.

These criteria were applied to all the reports and studies found after an extensive search. The addition of country/region names in the search responded to the need of knowing how particular regions of interest were dealing with health inequalities. Interest in regions was mainly based on previous knowledge of concrete public health organizations studying those regions, as well as interest in looking for other organizations in charge of tackling health inequalities in regions similar to Catalonia. Nevertheless, as in any review, it is not possible to ensure that absolutely all the reports suitable for this study were found during the search, nor that they were selected after applying the selection criteria.

Grouping health indicators into topics

As stated above, the most frequent health indicators were grouped into topics according to the health domain they were measuring (with each indicator related to only one topic). For example, although “ Percentage of 15-year-olds who were overweight in 2009–10, EU Member States by sex ” [ 25 ] and “ Obesity rate by body mass index (BMI) (sdg_02_10) ” [ 23 , 66 ] are different indicators per se, they are both intended to measure the same health issue and, hence, were grouped under the same topic “Obesity and overweight (BMI)” under the indicator name “Obesity and/or overweight (total, by sex, age, or educational level)”.

Most of the selected health indicators were taken from the official statistics of different countries or international organisations, whose development and methodology has been closely consolidated over many years and respond to international standards. In addition, most of these indicators are related to relevant knowledge areas for the study of health inequalities, such as lifestyle habits, deprivation, and mortality .

To prioritise the most relevant topics, all the groups with less than five health indicators were deleted. This meant that, unfortunately, interesting topics such as the “Years of potential life lost” [ 34 , 36 , 42 ], “Unmet health needs” [ 23 , 26 , 39 ] and “Passive smokers” [ 33 , 34 ] were not taken into consideration. Nevertheless, this selection does not imply per se a periodic monitoring of the selected health indicators, as specific topics not present in this list may be studied according to ultimate needs.

Relevance of the most common topics

All the topics aim to measure and study the relation between determinants of health and health outcomes. Interestingly, three of the top five topics in the list (see Table 2 ) are related to mortality: life expectancy, infant mortality, and mortality rate. Life expectancy at birth is an indicator of mortality conditions and, by proxy, of health conditions [ 44 ]. Hence, life expectancy as well as other mortality-related topics are widely used in the study of health inequalities.

Living and working conditions, such as BMI or smoking, are also key factors in the study of health inequalities as both share a strong socioeconomic gradient [ 54 , 56 ]. Therefore, as may be expected, they appeared among the top 10 positions in the list of topics (see Table 2 ). According to our review, the most common way to measure socioeconomic status is to analyse the unemployment rates and material deprivation level of the population.

In Spain, some regions use less common health indicators for studying health inequalities that may be interesting for particular knowledge areas. For example, the Valencian Observatory of Health uses the “Caregiver profile”, which they report to be mostly women, without primary studies, 57-years-old on average, and reporting bad self-perceived health. In addition, they also use “Reasons why contraceptive methods are not used by age and nationality of women” as well as a “Sexual-health information resources (school, parents, friends, etc.)”, which may help to understand possible sexual health inequalities [ 43 ]. In the Andalusian School of Public Health, the indicator “Psychosis and mental illnesses due to drugs or alcohol abuse” may be helpful to estimate various negative health outcomes of alcohol and substance abuse that the healthcare system will need to address [ 41 ]. Even so, more than a half of topics in Table 2 appear in their reports.

As may be expected, the health indicators used in other reports produced by the Catalan Health System Observatory, such as the “Community Health Indicators”, match the implicit measurement concept behind many of the topics: obesity and overweight, mortality by age (including infant), self-perceived health, and population with primary studies are some of them [ 67 ].

- Health indicators

As can be seen in Table 3 , health indicators were combined within each topic if stratifiers such as population sex, age, or region were the only difference in their calculation methodologies. Some indicators were also merged if they were formerly different in the way they expressed the same data (i.e., raw number, rate per 1000 or 100,000).

The health indicators within each topic often cover a different aspect relevant to health inequalities. For example, in the topic “Tuberculosis” [ 23 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 40 , 42 , 43 ] indicators about incidence, prevalence, or mortality can be observed. In addition, health indicators about treatment coverage or vaccination are also included in this topic. Overall, in most topics, indicators try to measure every relevant (and measurable) aspect of the topic.

Common stratifiers are sex, age, and studied region, something that is coherent with the determinants of health perspective and the focus on inequalities. However, the stratifiers found are highly heterogeneous and may also include socioeconomic status, educational level, or nationality/country of origin, among many others.

Research fitted to monitor health inequalities

This comprehensive review was carried out to help accomplish the first step in the process for tackling and monitoring health inequalities: selecting high-impact issues and health indicators [ 19 , 20 ]. The next steps in the analysis will be to carefully take into account stratifiers such as area of residence, gender, age, and nationality. Lastly, after the identification of key health inequalities, decision-making stakeholders will need to play a role during the last steps: determining priorities of action and implementing changes. The time variable will play a key role in the monitoring, as it will indicate the possible health consequences of policy-making decisions [ 19 , 20 ].

Reviewing the most common health indicators and topics used in the study of health inequalities may help research teams in different ways. First, having an overview of what is being done by their neighbouring countries or regions may highlight issues that should not be missed when selecting relevant health topics to study. Second, even if some topics might not ultimately be chosen as a priority of action, having a complete list of key issues will provide an overview of what is relevant in the study of health inequalities, as well as some interesting insights. Lastly, knowing what other research institutions are working on will promote potential collaborations between organizations, creating synergies and bonds that may lead to better understanding and monitoring of health inequalities.

At a regional level, these results are highly valuable for the first stages of health inequalities monitoring cycles in Catalonia. This study provided the basis for choosing health topics to study as well as helped gain insights about which indicators should be used. In addition, regions with similar socioeconomic status and goals in tackling health inequalities may benefit from this research. Similarly, at a national and international level these results may help organizations shift the focus towards undermined health inequalities topics or explore new areas of knowledge (yet unstudied or with a different perspective).

Availability of data and materials

No analysis of quantitative data was performed. Hence, data availability declaration is not applicable.

Abbreviations

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

Acute myocardial infarction

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

Body mass index

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Comisión para Reducir las Desigualdades Sociales en Salud en España

Cardiovascular disease

European Core Health Indicators

12-Item General Health Questionnaire

General practitioner

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Healthy Life Years

International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification

International Health Regulations

National Health Service

Portable document format

Public Health Agency of Canada

Interdepartmental and Intersectorial Public Health Plan

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

Sustainable Development Goals

Socioeconomic status

Slope index of inequality

Tuberculosis

Uniform resource locator

United Nations

World Health Organization

World health organization (WHO). Meeting report of the world conference on social determinants of health. Rio de Janeiro, 19-21. Geneva: WHO; 2011. p. 2012. http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/wcsdh_report/en/ . Accessed 24 July 2019

Google Scholar

Comisión para Reducir las Desigualdades Sociales en Salud en España. Propuesta de políticas e intervenciones para reducir las desigualdades sociales en salud en España. Gac Sanit. 2012:182–9.

Comisión para Reducir las Desigualdades Sociales en Salud en España. Análisis de situación para la elaboración de una propuesta de políticas e intervenciones para reducir las desigualdades sociales en salud en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social; 2009. http://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/promocion/desigualdadSalud/docs/Analisis_reducir_desigualdes.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019.

Comisión para Reducir las Desigualdades Sociales en Salud en España. Avanzando hacia la equidad: propuesta de políticas e intervenciones para reducir las desigualdades sociales en salud en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social; 2010. http://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/promocion/desigualdadSalud/docs/Propuesta_Politicas_Reducir_Desigualdades.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019.

World Health Organization (WHO). Rio political declaration on social determinants of health Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Geneva: WHO; 2011. p. 2012. https://www.who.int/sdhconference/declaration/en/ . Accessed 24 July 2019

Working Group for Monitoring Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Towards a global monitoring system for implementing the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health: developing a core set of indicators for government action on the social determinants of health to improve health equity. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):136.

Article Google Scholar

Government of Catalonia. Health plan for Catalonia 2016–2020. Barcelona: Ministry of Health of Catalonia; 2016. http://salutweb.gencat.cat/web/.content/_departament/pla-de-salut/Pla-de-salut-2016-2020/documents/health-plan-catalonia_2016_2020.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019

Comissió Interdepartamental de Salut. Pla interdepartamental i intersectorial de salut pública. Barcelona: Ministry of Health of Catalonia; 2017. http://salutpublica.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/aspcat/sobre_lagencia/pinsap/01Els_Plans/PINSAP_2017-2020/PINSAP_2017-2020-Complet.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019

Cabezas-Peña C. Catalonia, Spain. Regions for Health Network (RHN). Geneva: WHO; 2018. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/373387/rhn-catalonia-eng.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019

Observatori del Sistema Salut de Catalunya. Efectes de la crisi econòmica en la salut de la població de Catalunya. Barcelona: Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia; 2014. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/contingutsadministratius/observatori_efectes_crisi_salut_document.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019

Observatori del Sistema Salut de Catalunya. Efectes de la crisi econòmica en la salut de la població de Catalunya. Anàlisi territorial. Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia: Barcelona; 2015. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/ossc_crisi_salut/Fitxers_crisi/Salut_crisi_informe_2015.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019

Observatori del Sistema Salut de Catalunya. Desigualtats socioeconòmiques en la salut i la utilització de serveis sanitaris públics en la població de Catalunya. Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia: Barcelona; 2017. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/ossc_crisi_salut/Fitxers_crisi/Salut_crisi_informe_2016.pdf . Accessed: 13 September 2019

Observatori del Sistema Salut de Catalunya. Central de Resultats: Efectes de la crisi econòmica en la població infantil de Catalunya. Barcelona: Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia; 2014. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/contingutsadministratius/observatori_efectes_crisi_salut_monografic.pdf . Accessed 20 March 2020

Observatori del Sistema Salut de Catalunya. Central de Resultats: Evolució de la utilització de serveis i el consum de fàrmacs 2008–2015. Barcelona: Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia; 2008. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/ossc_central_resultats/informes/fitxers_estatics/MONOGRAFIC_25_CRISI_EVOLUCIO_2008-2015.pdf . Accessed 20 Mar 2020

García-Altés A, Ruiz-Muñoz D, Colls C, Mias M, Martín BN. Socioeconomic inequalities in health and the use of healthcare services in Catalonia: analysis of the individual data of 7.5 million residents. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72(10):871–9.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ruiz-Muñoz D, Colls C, Mias M, Martín N, García-Altés A. Desigualtats socioeconòmiques en la salut i la utilització dels serveis sanitaris públics en la població de Catalunya. Ann Med. 2017;100:172–6 https://www.academia.cat/files/499-448-FITXER/provesievidencies1.pdf . Accessed 20 Mar 2020.

Genoveva B, Ruiz-Muñoz D, García-Altés A. Efectes de la crisi econòmica en la salut de la població de Catalunya: anàlisi territorial. Ann Med. 2016;99:126–31 https://www.academia.cat/files/499-386-FITXER/provesievidencies.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019.

Health for Everyone?. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD; 2019. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-for-everyone_3c8385d0-en . Accessed 9 Jan 2021.

World Health Organization (WHO). Handbook on health inequality monitoring with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

UK Department of Health. Health equity audit: a self-assessment tool. London: Department of Health, 2004: 25. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120105214155/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4070715 . Accessed 13 Sept 2019.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. Health 2020: A European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. Geneva: WHO; 2013:190. http:// www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/199532/Health2020-Long.pdf . Accessed 24 July 2019.

Pencheon D. The good indicators guide: understanding how to use and choose indicators. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/the-good-indicators-guide-understanding-how-to-use-and-choose-indicators . Accessed 25 Mar 2020

Eurostat. SDG 3. Good health and well-being. Luxembourg: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/sdi/good-health-and-well-being . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

ECHI-European Core Health Indicators. Luxembourg: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/health/indicators/echi/list_en#id3 . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

Marmot M. Health inequalities in the EU - final report of a consortium. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2013. [ https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/social_determinants/docs/healthinequalitiesineu_2013_en.pdf ]. Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Social Protection Committee. Indicators Sub-group. Portfolio of EU social indicators for the monitoring of progress towards the EU objectives for social protection and social Inclusion. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2015. http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=14239&langId=en . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

I2sare project. Galicia, Spain profile. Regional Health Profiles in the European Union, 2010. www.sergas.es/Saude-publica/-I2SARE-Galicia . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Data Management Tool. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. http://dmt.euro.who.int/classifications/tree/B#B02 . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). 100 core health indicators (plus health-related SDGs). Geneva: WHO; 2018. www.who.int/healthinfo/indicators/100CoreHealthIndicators_2018_infogr.April 2020. Accessed 8 April 2020

The World Bank. Health. Data. Washington DC: The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/topic/health . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

Observatori Social d'Andorra. Sant Julià de Lòria (Andorra): Centre d’Estudis Andorrans. Govern d'Andorra https://observatorisocial.ad/index.php . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

Turrell G, Stanley L, de Looper M. Oldenburg B. Health inequalities in Australia: morbidity, health behaviours, risk factors and health services use (AIHW). Canberra; 2006. www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/0cbc6c45-b97a-44f7-ad1f-2517a1f0378c/hiamhbrfhsu.pdf . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2018. http://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary.html . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Canadian Institute of Health Information. Health Inequalities Data Tool. Ottawa: Government of Canada https://health-infobase.canada.ca/health-inequalities/data-tool/index . Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

Institute of Health Equity. Marmot indicators release 2017. London: Institute of Health Equity; 2017. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/about-our-work/marmot-indicators-release-2017 . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

NHS England Analytical Services & the Equality and Health Inequalities Unit. England Analysis: NHS Outcome Framework Health Inequalities Indicators. London: NHS England; 2016. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/nhs-outcome-framework-health-inequalities-indicators-2016-17.pdf . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Scottish Government. Long-term monitoring of health inequalities. Scottish Government: Edinburgh; 2018. http://www.gov.scot/publications/long-term-monitoring-health-inequalities-december-2018-report . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Buzeti T, Djomba JK, Blenkuš MG, Ivanuša M, Klanšček HJ, Kelšin N, et al. Health inequalities in Slovenia. Ljubljana: National Institute of Public Health; 2011. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/131759/Health_inequalities_in_Slovenia.pdf . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Ministry of Health and Social Policy of Spain. Moving forward equity in health: monitoring social determinants of health and the reduction of health inequalities. Madrid: Ministry of Health and Social Policy of Spain; 2010. http://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/promocion/desigualdadSalud/PresidenciaUE_2010/conferenciaExpertos/docs/haciaLaEquidadEnSalud_en.pdf . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Instituto Nacional de Estatística-Statistics Portugal. Indicadores Sociais 2011. Lisbon: Instituto Nacional de Estatística-Statistics Portugal; 2012. https://censos.ine.pt . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

García-Calvente MM, del Río LM, Marcos-Marcos J. Guía de indicadores para medir las desigualdades de género en salud y sus determinantes. Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública. Junta de Andalucía: Granada; 2015. http://www.easp.es/project/guia-de-indicadores-para-medir-las-desigualdades-de-genero-en-salud-y-sus-determinantes . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Malmusi D. Desigualtats en salut, respostes a nivell local: Polítiques per reduir les desigualtats en salut a la ciutat de Barcelona. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona; 2017. http://www.consorci.org/media/upload/arxius/coneixement/salut-publica/2017/D_%20Malmusi_Desigualtats_28-09-2017.pdf . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Observatorio Valenciano de la Salud. Desigualdades en Salud en la Comunidad Valenciana. Valencia: Generalitat. Conselleria de Sanitat Universal i Salut Pública; 2018. http://www.sp.san.gva.es/DgspPortal/docs/20180301_Desigualdades_Salud_OVS2018.pdf . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

United Natios (UN). Life expectancy at birth. New York: UN. http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/natlinfo/indicators/methodology_sheets/health/life_expectancy.pdf . Accessed 19 Mar 2020.

Shryock HS, Siegel JS, Stockwell EG. The methods and materials of demography. San Diego: Academic Press; 1976.

Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. Infant mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018. http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/neonatal_infant/en/ . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

Porta M, editor. A dictionary of epidemiology, sixth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199976720.001.0001/acref-9780199976720 . Accessed 8 Apr 2020

World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1 . Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Diabetes. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1 . Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). HIV/AIDS. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/health-topics/hiv-aids#tab=tab_1 . Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Tuberculosis. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/health-topics/tuberculosis#tab=tab_1 . Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden A, Wright K, Whitehead M, Petticrew M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(4):284–91.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms-Unemployed–ILO Definition. Paris: OECD; 2003. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp? ID=2791. Accessed 7 Apr 2020

Pigeyre M, Rousseaux J, Trouiller P, Dumont J, Goumidi L, Bonte D, et al. How obesity relates to socio-economic status: identification of eating behavior mediators. Int J Obes. 2016;40(11):1794–801.

Article CAS Google Scholar

World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight . Accessed 7 Apr 2020

WHO, Tobacco and inequities Guidance for addressing inequities in tobacco-related harm Written by: Belinda Loring. 2014.

World Health Organization (WHO). Harmful use of alcohol. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/health-topics/alcohol#tab=tab_1 . Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Physical activity. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity . Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

American Psychological Association (APA). Socioeconomic Status. Washinton DC. http://www.apa.org/topics/socioeconomic-status/ . Accessed 6 Apr 2020.

Eurostat. Glossary: Material deprivation - Statistics Explained. Luxembourg: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Material_deprivation . Accessed 6 Apr 2020.

Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2010. p. 79.

Salcedo N, Saez M, Bragulat B, Saurina C. Does the effect of gender modify the relationship between deprivation and mortality? BMC Public Health. 2012;12:574.

Regidor E, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, de la Fuente L. Has health in Spain been declining since the economic crisis? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(3):280–2.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Consulting Services Limited ICF. Towards a fairer and more effective measurement of access to healthcare across the EU final. London: ICF; 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/cross_border_care/docs/2018_measurement_accesstohealthcare_frep_en.pdf . Accessed 6 Apr 2020

Ebinger JO, Hamso B, Gerner F, Lim A, Plecas A. Europe and Central Asia region. New York: World Bank; 2008. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/25984 . Accessed 6 Apr 2020

Book Google Scholar

Eurostat. Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table. Luxembourg: European Commission; 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=sdg_02_10&plugin=1 . Accessed 28 Feb 2020

Catalan Healthcare System Observatory. Indicadors de salut comunitària. Barcelona: Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya. Departament de Salut; 2017. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/ca/observatori-desigualtats-salut/indicadors_comunitaria/ . Accessed 25 Mar 2020

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Neus Carrilero-Carrió (Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya (AQuAS), Barcelona, Spain) for support in reviewing drafts and assistance with writing.

All the activities performed were funded by the Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya (AQuAS) and CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Catalan Health System Observatory, Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya (AQuAS), 81-95 (2a planta), 08005, Barcelona, Spain

Sergi Albert-Ballestar & Anna García-Altés

CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain

Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica (IIB Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain

Anna García-Altés

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SA performed the main bibliographic review as well as the selection and organisation of health indicators and topics. AGA supervised the whole process, contributed to the conceptualisation of the paper and provided extensive comments and improvements to the drafts. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna García-Altés .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Albert-Ballestar, S., García-Altés, A. Measuring health inequalities: a systematic review of widely used indicators and topics. Int J Equity Health 20 , 73 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01397-3

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2020

Accepted : 28 January 2021

Published : 10 March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01397-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health inequalities

- Health policy

International Journal for Equity in Health

ISSN: 1475-9276

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Transforming health systems to reduce health inequalities

Sarah sowden, jasmine olivera, clare bambra, alex gimson, rob aldridge, carol brayne.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr John Ford, Forvie Site, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0SR, UK. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @johnford1849

Never before in history have we had the data to track such a rapid increase in inequalities. With changes imminent in healthcare and public health organisational landscape in England and health inequalities high on the policy agenda, we have an opportunity to redouble efforts to reduce inequalities.

In this article, we argue that health inequalities need re-framing to encompass the breadth of disadvantage and difference between healthcare and health outcome inequalities. Second, there needs to be a focus on long-term organisational change to ensure equity is considered in all decisions. Third, actions need to prioritise the fundamental redistribution of resources, funding, workforce, services and power.

Reducing inequalities can involve unpopular and difficult decisions. Physicians have a particular role in society and can support evidenced-based change across practice and the system at large. If we do not act now, then when?

KEYWORDS: health inequalities, equity, health systems, healthcare organisations

Introduction

For the first time in history we have the empirical data to witness a rapid compounding of existing inequalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for lower socio-economic and minority ethnic groups. 1,2 In the UK, deaths in the most deprived areas are double those in the least deprived (age–sex standardised rate in the least deprived areas are 350 deaths per 100,000 compared with 669 in the most). 3 In the USA and UK, deaths are up to three times higher in minority ethnic groups. 4 The current crisis represents a syndemic pandemic; the intertwined, interactive and cumulative effects on health and wellbeing of the COVID-19 pandemic combined with substantial existing socio-economic inequalities across life courses and in communities. 2

Despite the policy prominence and various frameworks focusing on health inequalities, healthcare leaders still do not feel they have the skills and knowledge to reduce health inequalities. 5–9 The underlying reasons for this may include a failure of researchers to provide accessible evidence on how to translate evidence into practice as well as a lack of a systematic and logical approach to inequalities for healthcare systems. 10–12 Physicians have a particular role in society and can support evidence-based change across practice and the system at large. Here, we first discuss the current policy and research context, then argue it is time for a re-framing of inequalities within healthcare systems, with a concerted effort to build a long-term organisational change to tackle inequalities head on, along with a wider redistribution of resources, funding, workforce, services and power across healthcare and wider society.

Policy, research and legislative context of health systems in the UK

In England, for the first time, key national and local NHS decision-making bodies were required by law to address inequalities in access and outcomes under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 13 This was the result of a growing body of literature showing sustained stark health outcome inequalities, dating back to the Black report, with inequalities in waiting times, patient experience and hospital admissions. 14–17 The Health and Social Care Act also shifted power from ministerial departments to NHS England with a decentralisation of decision making to local health systems. Despite the statutory responsibility, the years after the enactment of the Health and Social Care Act were dominated by reorganisation with considerable fragmentation of previously aligned services. Reforms were undertaken in the name of efficiency with poor evidence of their impact, rising costs to the health system and little progress on health inequalities, despite the clear negative health and wellbeing impacts of austerity and welfare reform. 18,19 Public health professionals classified the risk of this reorganisation to widen health inequalities as ‘extreme’. 20

In 2019, the NHS in England was asked to develop its own plans for a £20 billion funding injection. High-level policy objectives and initiatives were outlined in The NHS Long Term Plan and, in turn, local healthcare systems were asked to develop their own local response plans. 21 Health inequalities were a prominent feature of the national The NHS Long Term Plan among other priorities, such as primary care workforce, integration, prevention, cardiovascular disease and cancer. The plan set out to establish a ‘more concerted and systematic approach to reducing health inequalities’ alongside a number of specific inequalities initiatives such as supporting minority ethnic groups. However, the plan and its subsequent supporting documents failed to outline how local and national systems could systematically approach health inequalities with an expectation that local healthcare systems would each develop their own approaches. Our own previous research has highlighted that this is challenging for local systems, resulting in local plans being vague and lacking a systematic or joined-up approach. 12 Furthermore, the lack of a national health inequalities strategy (like that successfully pursued between 2000 and 2010) makes it harder to effect change across local health systems. 22,23

In response to COVID-19 inequalities data, NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE/I) published eight urgent actions to address health inequalities, including directives protecting the most vulnerable, improving recording, strengthening leadership and increasing preventative measures. 24

The structure of the NHS has moved substantially from its inception, through many re-disorganisations and, lately, the statutory bodies established under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. More recently, integrated care systems have been established, which are likely to merge with clinical commissioning groups. 25 It is likely that further health and social care legislation, under the advice of NHSE/I, will be passed in the near future to catch up with the organisational evolution. 26

Only 7 years after its formation, Public Health England (PHE) is already being disestablished. PHE was set up to protect and improve the nation's health and reduce health inequalities. 27 One action of the Health and Social Care Act was the extraction of public health skills from leadership roles within the NHS, something that was an obvious gap immediately after revealing a lack of understanding of the key role of public health leadership and skills in health and social care systems. This has become critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, as more public health leadership in the health and social care system may have improved the response.

Health inequalities have been a common thread across PHE activities. While trying work across organisational boundaries, these have included the provision of data on health inequalities, guidance, evidence-based tools for local health systems, advice to national government and focused action on inequalities in screening and immunisations. 5 , 28–31 PHE have particularly promoted a place-based approach to inequalities. 5 Under current plans PHE's health protection functions will be taken over by the National Institute for Health Protection, but the future location of the other PHE functions is still under discussion.

The research community has been driving forward the inequalities' agenda. The Academy of Medical Sciences published their report Improving the health of the public by 2040 promoting a health of the public research approach with a strong emphasis on health equity. 32 In response to this, the Strategic Coordination of the Health of the Public Research committee (SCHOPR) was established and has set out its guiding principles on population research, including a priority of focused investigation into how interdisciplinary research can reduce inequalities. 33 Furthermore, the Academy of Medical Sciences has recently written to the secretary of state outlining the need to prioritise prevention and improvement to reduce inequalities. 34

More recently, the Royal College of Physicians have convened a coalition of over 140 organisations to campaign for a cross-government strategy to reduce inequalities, the commencement of the socio-economic duty in the Equality Act and prioritising child health in public policy. 35

With the healthcare and public health reform afoot, inequalities highlighted due to the pandemic are thus high on the policy agenda, and a mobilised research community, it is time to rethink our approach to inequalities within and beyond the healthcare system. Without clarity, sufficient prioritisation and leadership any actions are at risk of only ever having a marginal impact.

Framing inequalities to ensure a systematic and logical approach in health systems

Framing is a way of structuring or presenting a problem and can be helpful, potentially vitally so, to ensuring action. 36 How we discuss and present inequalities must be developed with and for any audience it is hoped might contribute to effective changes; for example, NHS staff are more likely to engage if inequalities are framed around healthcare and the specific services for which they are responsible, such as inequalities in chronic disease management or non-elective admissions alongside concrete actions, rather than high-level more abstract health outcome inequalities, such as differences in life expectancy. 37 A lack of adequate framing brings risks. Focusing only on high level inequalities with healthcare staff, such as life expectancy, may lead to a sense of fatalism because these inequalities are primarily driven by geo-political factors outwith the influence of local health systems and their leaders; or a belief that downstream individual actions targeted at the social determinants of health will reduce inequalities. 38–40 In turn, these may lead to a health inequalities fatigue where motivation for action on inequalities wains due to short-termism and a perceived lack of progress.

A broad framing of inequalities highlighting how multiple different aspects of disadvantage lead to substantial differences in healthcare and health outcomes is needed to allow decision-makers to develop their own systematic and logical approach to doing what is within their power and advocacy to reduce inequalities. Without this systematic approach, there is a risk of an unequal focus on certain groups at the expense of others, such as focusing on the so-called ‘deserving poor’ at the expense of the ‘undeserving poor’. 41 Our review of local NHS plans revealed that systems focused more on people with learning difficulties and autism, but less so on undocumented migrants, people who are transgender or those with justice service involvement. 12 This creates inequalities within inequalities.

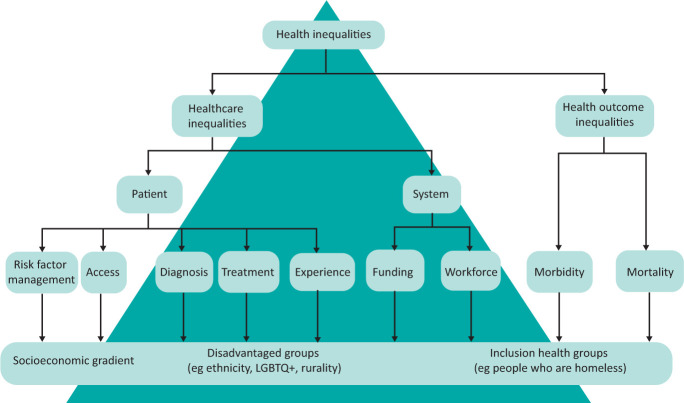

Inequalities must be framed and measured to include both healthcare (eg risk factor management, access, diagnosis, treatment and experience) and health outcome (eg morbidity and mortality) inequalities (Fig 1 ). Key components across the spectrum of health and care include the distribution of health system resources (namely funding, workforce and research distribution, and training), access to and quality of healthcare, major drivers of mortality and morbidity (eg cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cancer, mental health and musculoskeletal conditions) and conditions which are intrinsically associated with inequalities (such as drug and alcohol abuse).

Unpacking health inequalities.

Framing should avoid language which is stigmatising or shaming. Smith and colleagues describe a paradox where people recognise that health is determined by social factors and acknowledged socio-economic inequalities in society, but are reluctant to acknowledge the resulting health inequalities. 42 The authors suggest this paradox arises because individuals do not want the place in which they live to be stigmatised, shamed, or have negative or derogatory connotations, which may have negative impacts on their employment opportunities or family. 43 Other studies have found that the idea of socio-economic health inequalities can be a source of stress for residents. 44,45

Building the long-term organisational change

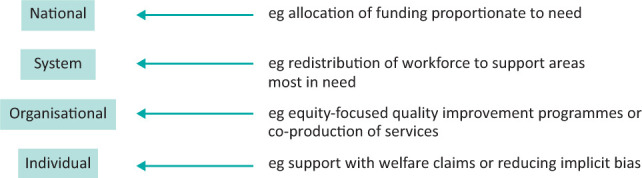

Many health inequalities have arisen over decades and even centuries, operating across generations and communities, due to long-standing imbalances in the social determinants of health. It is noteworthy that the north-south pattern of deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, almost exactly mirrors the distributions of COVID-19 deaths over a century later. 46 New manifestations of inequalities emerge over time, often with the promise of solutions and enthusiasms from new technologies. Previously this was the offer of screening, known to be taken up preferentially by more advantaged in society, and more recently in access to digital healthcare services with clear differential access. 47 In light of the plethora of existing and emerging inequalities, many feel a moral duty to ‘do something’, including investments in actions that lack a strong evidence base or sustainability (such as social prescribing or hospitals acting as anchor institutions). 48 It is important, therefore, for the NHS to resist the temptation to reach for such short-term actions at the expense of focusing on the long-term organisational change required for sustained and evidenced-based action. With the formation of integrated care systems in the NHS in England we have the opportunity to ensure an equity perspective is adopted from the start, maximising the opportunities of integrated working across health and social care. However, we need inequalities actions at all levels of healthcare, including national, system, organisational and individual (Fig 2 ).

Levels of health inequalities actions.

Much health data, particularly within hospitals, is not presented by socio-economic group, geographical disadvantage or ethnicity. The NHS eight urgent actions to address inequalities aims to improve ethnicity recording. 24 More upskilling is needed to help healthcare analysts undertake equity analyses to explore the difference between groups, adjusting for age and gender where appropriate. Equity perspectives are still rarely considered in healthcare quality improvement programmes, clinical audits, service evaluation or adverse events investigation; for example, hospital-based quality improvement programmes should consider if the services changes improve quality of care across socio-economic groups and ethnicity equally. Adverse event investigations should include an exploration how healthcare supported (or not) patients who are disadvantaged, for example due to poor health literacy or social support, interacted with services.

Previous research suggests that equity-focused processes can support healthcare organisations, their teams and individuals within these to address inequalities. 49 Health inequalities impact assessment is a process of exploring and mitigating the impacts of decisions on inequalities during decision making. Sadare and colleagues found that health inequalities impact assessment, if undertaken a meaningful way, can be a catalyst for equity-focused organisational change. 49 These could be used by clinical directors and hospital leaders to ensure that secondary care services do not increase inequalities.

Applied research has an vital role to play in exploring the distributional effects of interventions across disadvantaged groups and generating evidence of what works to reduce inequalities. 50,51 The evidence produced by current research poorly represents those who are most disadvantaged. The SCHOPR principles call for co-produced, transdisciplinary research to create and deliver targeted national and local solutions to reduce inequalities. 33 More research is needed to develop and understand the implementation of evidence-based solutions drawing upon disciplines such as geography, anthropology, sociology, economics and history. Research capacity and skills must be embedded in the organisations which emerge from the latest restructure to help them become learning systems.

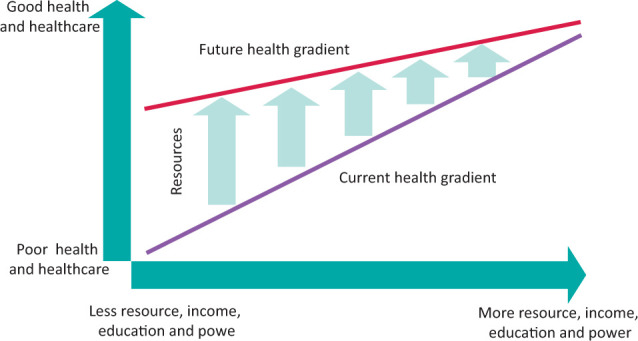

Redistributing resources and power to prevent illness and promote health

Inequalities are caused by the unequal distribution of social determinants of health, public and private investment, public sector workforce, services and power (the ability of one section of society to control another). 52 Without a fundamental change to how society can organise itself to address these, inequalities in health outcomes will persist. However, even within the way we organise ourselves currently and contrary to the sense that nothing can be done, there is evidence that the NHS can reduce inequalities. One example is an analysis of the increase of NHS resources to more deprived areas between 2001 and 2011, revealing a reduction in inequalities from causes amenable to healthcare. 53 This complements the principle of proportionate universalism, which states services should be accessible to all, but the intensity of the service should be proportionate to need with the most disadvantaged receiving more resources (Fig 3 ). 14 While existing national NHS allocation formulae are weighted for deprivation, evidence suggests they do not go far enough; and, in England, the weighting was reduced after the 2011 Act. 54

Distributing resources proportionate to need.

Beyond specific healthcare system evidence, there is also good evidence that cross government action can reduce inequalities. 22,23 Over the last couple of decades, there has been a natural experiment at a national scale. The UK government implemented a cross-government health inequalities programme and strategy from 2000 to 2010. Prior to the start of the programme, the difference in life expectancy between the most deprived areas and the rest of England was increasing by 0.57 months per year for males and 0.30 months per year for females. 22 The strategy reversed these trends with the gap in life expectancy reducing by 0.91 months per year for men and 0.50 months per year for women. Inequalities in the infant mortality rate (IMR) also decreased. 23 However, since the end of the strategy and the implementation of austerity, the inequality gap widened again by a similar amount as before and there is now evidence of increasing inequalities in IMR associated with rising rates of child poverty. 23 Key to the programme was a redistribution of funding, services and power to poorer areas, with regeneration initiatives, Sure Start centres to support early years childcare, increased NHS funding allocations, introduction of national minimum wage, more generous tax and benefit changes targeted at child poverty and targeted services in the most deprived local authorities. Unfortunately, detailed independent evaluation was not embedded or undertaken, and therefore the specific factors, either individually or collectively, which contributed to the observed narrowing inequalities gap remain unknown.

The importance of prevention and health promotion has been highlighted in several key documents. 24,34 The irony is that the under the Health and Social Care Act, public health was taken out of the NHS, but the current The NHS Long Term Plan prioritises prevention. Greater clarity is needed to ensure that the manner in which this emphasis is implemented does not unintentionally widen the gap. 55,56 For example, those with the resources and capabilities to benefit from an untargeted physical activity campaign have been and already are the more affluent groups with financial resources, health literacy and employment flexibility. This is also replicated within our research programmes and recruitment, which in many clinical research spheres do not represent diverse and disadvantaged communities. Policy makers should avoid the temptation to think that unhealthy lifestyles in people living in poorer areas arise because of a lack of knowledge or motivation and that the solution is information campaigns. 52,57 Decades of research reaching has demonstrated again and again that people, whether from poor or rich backgrounds, understand the determinants of health and have logical reasons for unhealthy choices. 57 For example, Graham found that pregnant women on low incomes still found money to buy cigarettes because smoking was the one opportunity in the day to do something for themselves in the context of very challenging life circumstances. 58 More recently, Thirlway found that smoking cessation was shaped by (lack of) social mobility. 59 To prevent illness and promote health we must break down the power hierarchies which suggest that one part of society knows what is best for another and get alongside people to understand why they act the way they do, treating them as experts in their lived experience, co-designing solutions as equal partners and advocating for the wider societal changes needed to address the social and economic context of inequality. 60

We all have an ethical and moral imperative to respond to the rapid proliferation of existing inequalities. Simultaneously, healthcare and public health organisations are being re-structured in England. We argue that the concept of health inequalities needs to be reframed to acknowledge the breadth of health and care inequalities with non-stigmatising language to ensure a systematic approach to the problem. A focus on building long-term equity-orientated organisational change in the NHS is urgently needed. At the core of any action should be the fundamental redistributions of resources, funding, workforce, services and power. If we do not act now in light of these stark inequalities, then when?

- 1. Public Health England . COVID-19: review of disparities in risks and outcomes. PHE, 2020. www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-review-of-disparities-in-risks-and-outcomes [Accessed 09 June 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74:964–8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Office for National Statistics . Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation. ONS, 2020. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19bylocalareasanddeprivation/deathsoccurringbetween1marchand17april [Accessed 03 May 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. APM Research Lab . The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths race and ethnicity in the US. APM Research Lab, 2020. www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race [Accessed Dec 29, 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Public Health England . Place-based approaches for reducing health inequalities: foreword and executive summary. PHE, 2019. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-inequalities-place-based-approaches-to-reduce-inequalities/place-based-approaches-for-reducing-health-inequalities-foreword-and-executive-summary [Accessed 05 September 2019]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. World Health Organization . A framework for measuring health inequality. WHO, 1996. www.who.int/healthinfo/paper05.pdf [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. NHS Health Scotland . Health inequalities action framework. NHS, 2013. www.healthscotland.scot/media/1223/health-inequalities-action-framework_june13_english.pdf [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Brooks D, Douglas M, Aggarwal N, et al. Developing a framework for integrating health equity into the learning health system. Learn Heal Syst 2017;1:e10029. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. NHS Confederation . Public reassurance needed over slow road to recovery for the NHS. NHS, 2020. www.nhsconfed.org/news/2020/06/road-to-recovery [Accessed 08 October 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Smith KE. Health inequalities in Scotland and England: the contrasting journeys of ideas from research into policy. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1438–49. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Smith KE. The politics of ideas: The complex interplay of health inequalities research and policy. Sci Public Policy 2014;41:561–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Olivera J, Ford J, Sowden S, Bambra C. Conceptualisation of health inequalities by local health care systems: a document analysis. [Under peer review, 2021]. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 13. Health and Social Care Act 2012. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/contents/enacted [Accessed 09 October 2019].

- 14. Marmot MG. Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot review; strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. Marmot Review, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. Department of Health and Social Care, 1998. www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-inquiry-into-inequalities-in-health-report [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. McIntosh Gray A. Inequalities in health. The black report: A summary and comment. Int J Heal Serv 1982;12:349–80. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Cookson R, Propper C, Asaria M, Raine R. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Health Care in England. Fisc Stud 2016;37:371–403. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Cheetham M, Moffatt S, Addison M, Wiseman A. Impact of Universal Credit in North East England: A qualitative study of claimants and support staff. BMJ Open 2019;9:29611. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Moffatt S, Lawson S, Patterson R, et al. A qualitative study of the impact of the UK ‘bedroom tax’. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:197–205. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Lambert MF, Sowden S. Revisiting the risks associated with health and healthcare reform in England: Perspective of Faculty of Public Health members. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:e438–45. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. NHS England . The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS, 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk [Accessed 09 July 2019]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Barr B, Higgerson J, Whitehead M. Investigating the impact of the English health inequalities strategy: Time trend analysis. BMJ 2017;358:j3310. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Robinson T, Brown H, Norman PD, et al. The impact of New Labour's English health inequalities strategy on geographical inequalities in infant mortality: A time-trend analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73:564–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. NHS England . Second Phase of the NHS Response to COVID-19. NHS, 2020. www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus [Accessed 03 May 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Brennan S. NHSE recommends law to abolish CCGs by 2022. HSJ; 2020. www.hsj.co.uk/commissioning/nhse-recommends-law-to-abolish-ccgs-by-2022/7029054.article [Accessed Nov 30, 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Alderwick H. NHS reorganisation after the pandemic. BMJ 2020;371:m4468. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Vize R. Controversial from creation to disbanding, via e-cigarettes and alcohol: an obituary of Public Health England. BMJ 2020;371:m4476. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Public Health England . Local action on health inequalities Understanding and reducing ethnic inequalities in health. PHE, 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/730917/local_action_on_health_inequalities.pdf [Accessed 10 September 2019]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Public Health England, Institute of Health Equity . Promoting good quality jobs to reduce health inequalities. PHE, 2015. www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/local-action-on-health-inequalities-promoting-good-quality-jobs-to-reduce-health-inequalities-/local-action-on-health-inequalities-promoting-good-quality-jobs-to-reduce-health-inequalities-full-report.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Public Health England . Supporting the health system to reduce inequalities in screening PHE Screening inequalities strategy Public Health England leads the NHS Screening Programmes. PHE, 2018. https://phescreening.blog.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/152/2018/03/Supporting-the-health-system-to-reduce-inequalities-in-screening.pdf [Accessed 12 June 2019]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Public Health England . Health Equity Assessment Tool [HEAT]. PHE, 2020. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-equity-assessment-tool-heat [Accessed 10 November 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. The Academy of Medical Sciences . Improving the health of the public by 2040. The Academy of Medical Sciences, 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Strategic Coordination of the Health of the Public Research committee . Health of the public research principles and goals. SCHOPR, 2019. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/70826993 [Accessed 28 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. The Academy of Medical Sciences . Future arrangements for prevention, health improvement and health protection. The Academy of Medical Sciences, 2020. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/90869115 [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Royal College of Physicians . Inequalities in Health Alliance. RCP, 2020. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/inequalities-health-alliance [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Blackman T, Harrington B, Elliott E, et al. Framing health inequalities for local intervention: comparative case studies. Sociol Health Illn 2012;34:49–63. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Ford J. Director's appointment should be used to reframe the debate around health inequalities. HSJ; 2020. www.hsj.co.uk/leadership/directors-appointment-should-be-used-to-reframe-the-debate-around-health-inequalities/7028959.article [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Green L. The concept of fatalism and New Labour's role in tackling inequalities. Br J Community Nurs 2001;6:106–11. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Schrecker T. Was Mackenbach right? Towards a practical political science of redistribution and health inequalities. Heal Place 2017;46:293–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Scott-Samuel A, Smith KE. Fantasy paradigms of health inequalities: Utopian thinking? Soc Theory Heal 2015;13:418–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Katz M. The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare. New York: Pantheon, 1989. [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Smith KE, Anderson R. Understanding lay perspectives on socioeconomic health inequalities in Britain: a meta-ethnography. Sociol Health Illn 2018;40:146–70. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Parry J, Mathers J, Laburn-Peart C, Orford J, Dalton S. Improving health in deprived communities: What can residents teach us? Crit Public Health 2007;17:123–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Davidson R, Mitchell R, Hunt K. Location, location, location: The role of experience of disadvantage in lay perceptions of area inequalities in health. Heal Place 2008;14:167–81. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Mackenzie M, Collins C, Connolly J, Doyle M, McCartney G. Working-class discourses of politics, policy and health: ‘I don't smoke; I don't drink. The only thing wrong with me is my health’. Policy Polit 2017;45:231–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Bambra C, Norman P, Johnson NPAS. Visualising regional inequalities in the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic in England and Wales. Environ Plan A Econ Sp 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Rich E, Miah A, Lewis S. Is digital health care more equitable? The framing of health inequalities within England's digital health policy 2010–2017. Sociol Health Illn 2019;41:31–49. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Sowden SL, Raine R. Running along parallel lines: How political reality impedes the evaluation of public health interventions. A case study of exercise referral schemes in England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:835–41. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Sadare O, Williams M, Simon L. Implementation of the Health Equity Impact Assessment [HEIA] tool in a local public health setting: challenges, facilitators, and impacts. Can J Public Heal 2020;111:212–9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Cookson R, Griffin S, Norheim O, Culyer A. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis. Oxford University Press, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Pons-Vigués M, Diez È, Morrison J, et al. Social and health policies or interventions to tackle health inequalities in European cities: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2014;14:198. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]