Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What Is Literary Theory and Why Do We Need It?

Alice Lopez

Too Long; Didn’t Read (TL; DR)

Literary theory is a set of tools we use to analyze and find deeper meaning in the texts we read. Each different theory sheds light on a specific aspect of literature and written stories, which in turn provides us with a focus for interpretation of them. You also might have heard of this kind of theory referred to as critical theory. According to Jonathan Culler, a Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Cornell University, what we refer to as theory “includes works of anthropology, art history, film studies, gender studies, linguistics, philosophy, political theory, psychoanalysis, science studies, social and intellectual history, and sociology” (3-4). These works have had an impact beyond the field of study they came from because their ideas are widely applicable, including to literature.

When we read literature, we tend to make sense of what we read through our own experiences. In the introduction to the book Literary Theory: An Introduction , Terry Eagleton explains that: “[…] we always interpret literary works to some extent in the light of our own concerns” (10). So in order to deepen our personal interpretation of a text and to explore different viewpoints on it, we rely on literary theory.

Literary theory is a critical approach that you can choose to focus your textual analysis. In this context, the word “critical” does not mean engaging in scathing commentary on a text. Rather, a critical approach is one where you evaluate what you read and think about it from different perspectives. The word theory, in this instance, is not as abstract as it may sound – a theory is just an idea that was explored in depth in order to explain and interpret complex social systems or phenomena. A theory is not something that is simple or obvious, as it must be researched and fleshed out, and it usually has not been created specifically for literature analysis. Instead, a theory is made of “[…] writings from outside the field of literary studies [that] have been taken up by people in literary studies because their analyses of language, or mind, or history, or culture, offer new and persuasive accounts of textual and cultural matters” (Culler 3-4). These writings from different fields help us use specialized knowledge. Depending on what you are most interested in exploring within a text, you will choose a theory that can provide the most insight into this specific area.

These different theories are sometimes described as critical lenses. I like to think of a critical lens as a set of colored glasses: when wearing them, some colors will be made less visible, while others will stand out and become easier to focus on. For example, imagine wearing glasses with pink lenses. Everything you see will have a pink tint to it, which will alter the way you see colors: some colors will be accentuated, while others (like blue light) will be less noticeable. Wearing the colored lenses might also change your depth perception, or how well you see the contours of your environment. In short, changing the color of the lens on your glasses will allow you to see a different view than you would with the naked eye. Theory does similar for a text, helping us see it with a different view than we could while reading it alone. Some of the most common and widely-used literary theories are psychoanalytic theory, feminist theory, structuralism/ post-structuralism, and Marxist theory.

In his introduction to literary theory, Jonathan Culler shares the following list of characteristics of theory:

- Theory is interdisciplinary – discourse with effects outside an original discipline

- Theory is analytical and speculative – an attempt to work out what is involved in what we call sex or language or writing or meaning or the subject

- Theory is a critique of common sense, of concepts taken as natural

- Theory is reflexive, or thinking about thinking; enquiry into the categories we use in making sense of things, in literature and in other discursive practices (14-15)

Note that using theory requires using ideas from different fields of study (interdisciplinarity) to explore ideas that we might take for granted: we must examine our views and thoughts about certain topics. It also asks that we read the text closely and engage in critical thinking to break down the story’s topics (analysis). Finally, working with theory means that we propose potential ideas to answer the questions we ask of the text (speculation).

Why would we need the help of theoretical texts to find new or deeper meaning in what we read? To put it simply, literary theory helps us understand what lies beneath the storyline and gives us the words to describe this. For example, by providing us with definitions, descriptions, and explanations of abstract ideas, literary theory becomes a means to explore the psychology of the narrative’s characters, delve into the historical and sociopolitical context of the story, or articulate the structure of the text, among other things. With literary theory, we can question the assumptions, values, and ideologies underlying the narrative.

Here is a quick example. Let’s pretend you are reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein for a class. You know that this book is one of the first examples of science fiction and in the genre of Gothic horror. Interestingly, at a time when most books were written by well-to-do men, this ever-so-famous classic was authored by a young woman between the ages of 18 and 19. As you read, you cannot help but think that the main protagonist, Victor, has a bit of a strange relationship with Elizabeth and with his mother. You can describe what takes place in the book and express your opinion, but you begin asking questions that go beyond the plot of the text itself. Are the characters acting within the boundaries of expected gender roles? Is Victor’s view of women common for the time? Are author Mary Shelley’s own attitudes about gender showing through her characters?

In order to take your analysis further, you pick a theory to work with. In this case, you decide to use feminist theory to think about gender roles in the book. If instead you had an interest in the economic power structure depicted in this book, then you could choose to analyze the text using Marxist theory. This critical lens focuses on the struggle between different social classes. In this case, Victor Frankenstein and his monster could be viewed as belonging to two different classes (bourgeois and proletariat, respectively). When viewed in this way, the struggle between these two characters and its resolution take on a different meaning (Moretti).

If you would like to see some examples of how to analyze a text with the writings of a theorist, I recommend Jonathan Culler’s “Chapter 1: What is Theory” in Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction .

Over time, philosophers and theorists from different fields of study have explored and offered many ideas to think about and make sense of our world. As literature became a field of study in “the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,” there was an “emergence of literary studies in universities in Germany, France, England, America, and elsewhere, and that institutional development made necessary the development of methods of teaching that were associated with methods for conducting literary research” (Ryan 3). For example, in the mid- to late-20th century, a movement called Postmodernism (led, among others, by philosophers like Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes) discussed how society defines some people as “other,” creating categories such as deviant . What these authors wrote can help us understand some of the social mechanisms in place to categorize us, to make us conform, and to control us. Another example of theory is postcolonialism, a school of thought that considers the impact of colonialism and offers ways to resist and unsettle colonial power structures. One last example of a framework you could work with is disability studies, a branch of study analyzing and questioning definitions of disability and the role of society in controlling and erasing the existence of disabled bodies and minds.

In a Lumen Learning article titled “Introduction to Critical Theory,” William Stewart provides a chronological list of critical theories. Here is an abbreviated version of this list:

- Aestheticism – often associated with Romanticism, a philosophy defining aesthetic value as the primary goal in understanding literature. (This includes both literary critics who have tried to understand and/or identify aesthetic values, as well as those like Oscar Wilde who have stressed art for art’s sake.)

- Cultural studies – emphasizes the role of literature in everyday life

- Deconstruction – a strategy of “close” reading that elicits the ways that key terms and concepts may be paradoxical or self-undermining, rendering their meaning undecidable

- Gender studies (see also: feminist literary criticism) – emphasizes themes of gender relations

- Formalism – a school of literary criticism and literary theory having mainly to do with structural purposes of a particular text

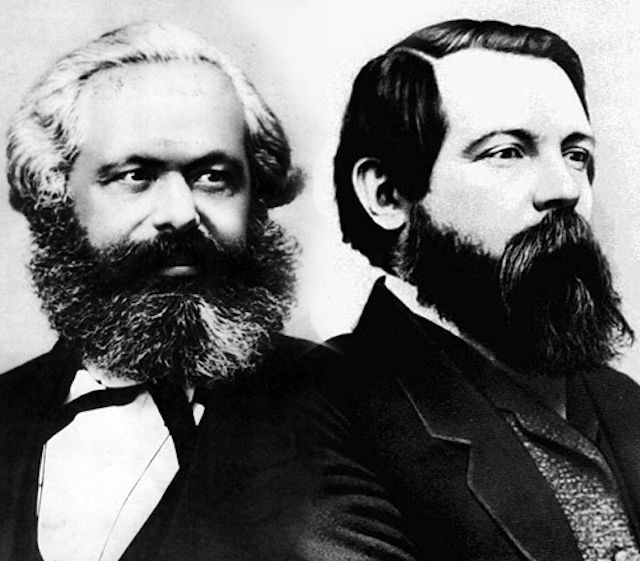

- Marxism (see also: Marxist literary criticism) – emphasizes themes of class conflict

- New Criticism – looks at literary works on the basis of what is written, and not at the goals of the author or biographical issues

- New Historicism – examines works through their historical context(s) and seeks to understand cultural and intellectual history through literature

- Postcolonialism – focuses on the influences of colonialism in literature, especially regarding the historical conflict resulting from the exploitation of developing countries and indigenous peoples by Western nations

- Postmodernism – criticism of the conditions present in the twentieth century, often with concern for those viewed as social deviants or the Other

- Psychoanalysis (see also: psychoanalytic literary criticism) – explores the role of consciousnesses and the unconscious in literature including that of the author, reader, and characters in the text

- Queer theory – examines, questions, and criticizes the role of gender identity and sexuality in literature

When it comes to applying these theories to literature, we start with the idea that a text is the product of its time: a reflection of society at the time and/or an expression of the author’s beliefs and views. Literature opens a window through which we can view a moment in time. We then explore some aspects of the text that we read through the lens of a theory.

You might be reading this article to prepare for a specific assignment. It is common for literature courses to ask students to analyze, interpret, and discuss the texts they read. You will generally begin to think about how you should analyze a text when you are engaging in close reading: you will notice recurring themes, salient ideas, etc. Depending on what interests you, you can then determine which theory (or theories) you would like to use.

While reading your text, you want to take notes about thoughts you have. You can take these notes in any way that works best for you: paper notepad, voice recordings, digital notepad, etc. Make sure to note page numbers, save important quotes, and document other relevant information so that you are able to reference your findings later. As you do so, you will notice patterns, or parts of the story will stand out to you. Reflect on why you are interested in specific aspects of the story, as this will guide you in choosing which theoretical framework to use. Your professor will likely have introduced you to a few literary theories. Ask yourself which one seems the most relevant to what you would like to analyze.

If you are writing an essay that uses literary theory, it could have the following structure:

- Briefly introduce the text you will be analyzing:

It is important to provide your audience with some information about when the text was written, to share a few details about the author, and to summarize the main plot points of the story.

- Share and explain the theory you will be using:

Once you have situated the text, you will write a couple of paragraphs where you name the theory you will be using, cite its main authors, and explain its most important or relevant ideas.

- Make a broader argument about the text:

This is where the analysis starts in earnest. You will draw out ideas from the theory you chose and analyze specific portions of your text with them. You will quote the text to show your audience specific examples of your argument. It is in this section that you will provide depth to your argument. Coming back to the earlier example of Frankenstein , you might have decided to look at the text through the lens of feminist theory. You describe the gender roles portrayed in the story and provide examples from the book showing that women tend to be confined to the home while men work outside. You explore whether this was traditionally the case at the time the book was written and argue that the gender roles in the story reflect that of the era. Continuing to rely on feminist theory, you could then explore whether the gender roles described in the book empower or subjugate the female characters, and you make sure to provide examples from the text to support your argument.

- Provide a conclusion:

Reiterate the main points you have made in the body of your paper. A conclusion is also a great opportunity to open your findings to broader interpretations.

By now, you should feel clearer on what constitutes literary theory and how it is used in analysis. You should also have a sense of the different theories available and their respective emphases. Literary analysis is a fantastic way to be curious about what lies beneath a narrative and to unsettle assumptions in the text. It offers frameworks to think critically about larger social questions, many of which still affect us today. Such analyses even provide us with opportunities to reflect on our own perceptions and biases. As literary theory enhances our critical skills and allows us to engage in deeper inquiries, we develop an important skillset that we can rely on in situations beyond the classroom.

Works Cited

Culler, Jonathan D. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford University Press, 1997.

Eagleton, Terry . Literary Theory: An Introduction, University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Moretti, Franco. Signs Taken For Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms. Verso, 1997.

Rivkin, Julie, and Michael Ryan, editor . Literary Theory: An Anthology. 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2017.

Ryan, Michael, editor. Literary Theory: A Practical Introduction. 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017.

Stewart, William. “Introduction to Critical Theory.” Lumen , https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-herkimer-english2/chapter/introduction-to-critical-theory/ . Accessed 31 March 2024.

About the author

name: Alice Lopez

institution: Salt Lake Community College

Alice Lopez is a professor in the D epartment of English, Linguistics & Writing Studies at SLCC. She r eceived her BA in Writing Studies and MA in Rhetoric & Composition from the University of Utah. She is currently a student in the Rhetoric & Composition PhD program at the U. She is interested in multimodal composition and disability studies. In her free time, Alice can be found taking photos, playing with fountain pens or typewriters, and taking care of her Sphynx cats .

Literary Studies @ SLCC Copyright © 2023 by Stacey Van Dahm; Daniel Baird; and Nikki Mantyla is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What is literary theory? An Introduction

What is literary theory? Let’s Understand!

This question pops up to me every time I meet youngsters who have just begun studying English literature. Moreover, also when I get together with research scholars and professors. And therefore, it would not be an exaggeration to say that literary theory is in fashion and it has been the case for a long time. Today, in this article, I would do my best to make sure that anyone who reads this article to the last line goes home with a complete understanding of the concept that we call literary theory. It should be interesting to note while many of us, students and beginners, know this or that thing about deconstruction, ecocriticism, structuralism and other theories, we seldom bother defining literary theory! Amusing, isn’t it? I have also made a video, short and comprehensive, on this topic and I will add that video here as well as on YouTube so that the readers who rather like to have a visual presentation can enjoy that as well. Without getting into the infinite of arguments and caveats, let’s get into the subject now.

Literary Theory: The idea before we get a suitable definition

The purpose of this section is to introduce the readers to the basics of literary theory before we get into defining that idea. The term theory generally hints at how & why of any execution, action or plan. Here also, even if we have added ‘literary’, the meaning of the term theory does not change. However, when we add literary before theory, we are certainly impacting the connotations. We are limiting the scopes of the term theory. So, the questions or notions relating to how and why of anything relating to literature will be dealt with by the concept called literary theory. Do you get this thing? In simple terms, the very idea of it concerns with literary interpretations, studies, assumptions and conclusions. It impacts the mindset of a reader during the reading of any literary work as well as during critically approaching any literary work. I hope the basic idea should have been easily understood by the readers by now. I will get to the best possible definition of our subject in the next section.

Definition of Literary Theory:

Though it would certainly be naive to put it forth, however, it is surprising that none of the authors with very wonderful titles in the field of literary theory have ventured to define this very thing called literary theory. It would certainly have been encouraging reading the definitions of this broadly-connoting idea by the scholars who have made name for themselves. However, since we don’t have that luxury, it is our job to make our efforts and try to construct a suitable definition. While there are many definitions already available on the internet, I think an easier, comprehensive and a little more than short definition would make the whole concept simple for beginners and comprehensive for advanced level students. Here is an attempt:

“A Literary Theory is a body of logically derived and not easily refutable ideas in a systematic order that we can use while we critically interpret a literary text.”

This definition leads us to understand the act called literary criticism and the person called a literary critic. The act of critically interpreting any literary text with a certain literary theory in mind is called literary criticism and the person involved in this intellectual (rarely emotional) exercise is called a literary critic . The act of literary criticism, in the modern context, has become synonymous (almost) with the idea tossed by I. A. Richards – practical criticism.

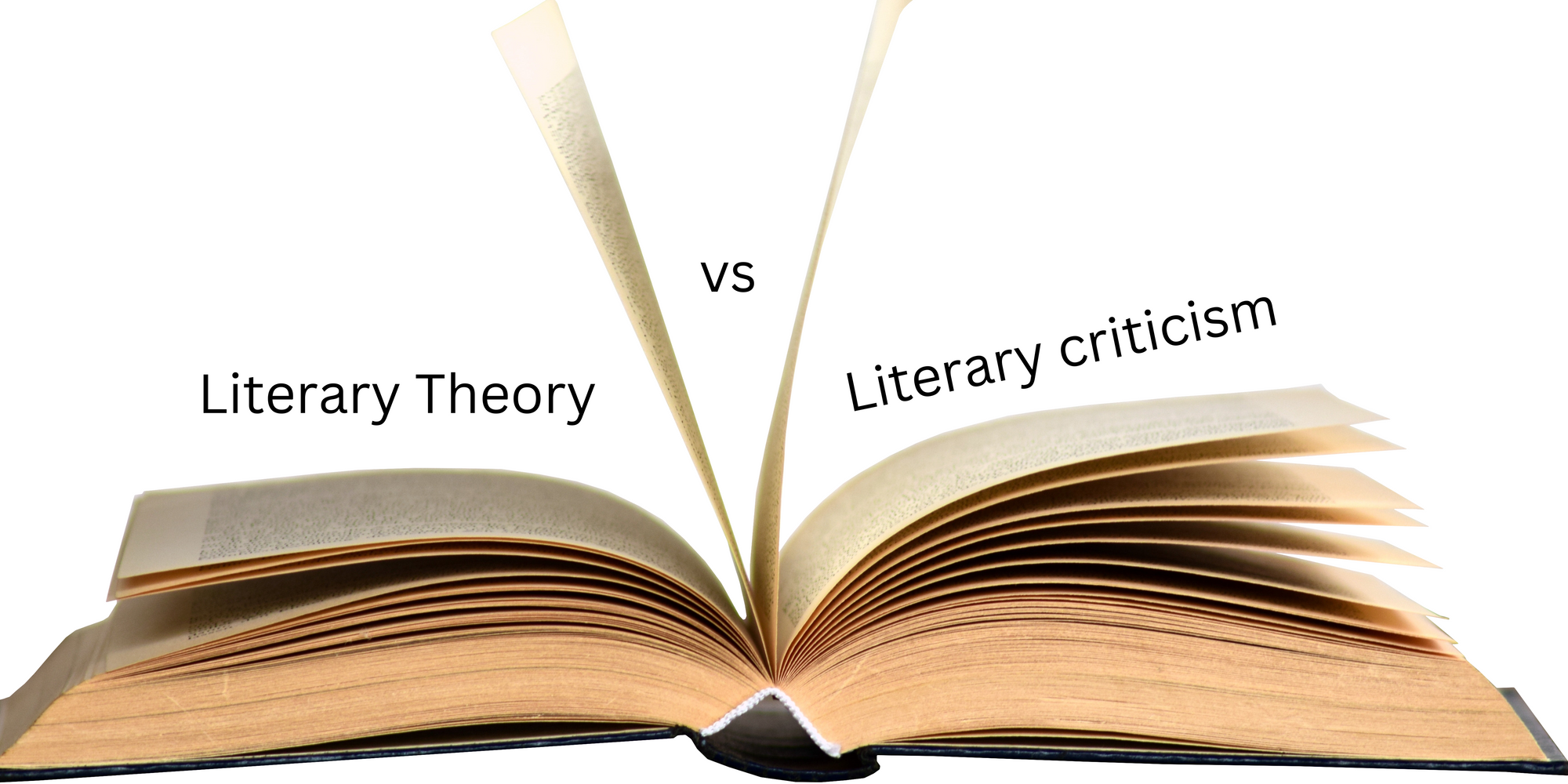

Relationship between Literary Theory & Literary Criticism:

To be frank, it is too naive a question to ask if someone really falls for it. What is the relationship between literary theory and literary criticism? Look at the names themselves. Both theory and criticism have literary as the prefix. Therefore, it is natural that there must be something common between them in the context of their concern with literature. A work of literature or a literary text becomes the playground where a literary critic comes up with a literary theory after an extensive analysis of the given text. Once the theory is established and becomes popular, other concerned people with literature learn about that particular literary theory and subsequently use that theory when they study any literary text in the direction specified in that particular theory. So, in short, the literary text is the basis of this relationship at the outset. This may have become an elaborated background but it was necessary for the beginners to understand the connection in the context of origins of literary theory and literary criticism.

Now, to cut things short and to establish the relationship at a logical level, between literary theory and literary criticism, a very simple idea can drive the cause to its conclusion. Any particular literary theory is the foundation for an act of literary criticism in a particular direction or context or purview. For example, Ecocriticism theory will be the foundation of any study undertaken by a scholar to trace the environmental references in the work of T. S. Eliot.

Though this was the shortcut to establish this relationship which was necessary because many students have asked me about it, I will be writing an entirely different article on this subject. That will be advanced in connotations and meanings and will be useful for those who want to dive to the depths of this wonderful relationship.

Differences between Literary Theory and Literary Criticism:

Once again, this question is too naive if someone asks what are the differences between literary theory and literary criticism. Why do I say so? This is too easy to comprehend. One is a set of ideas or rules that become guiding principles for an act that is called literary criticism. So, the basic and the fundamental difference between literary theory and criticism is that one is theoretical and another is practical. Literary theory is the theoretical part and literary criticism is the practical part of the same larger idea that concerns with the analysis of a literary text.

Like I shared above, I will also be writing an entirely different piece on this subject. I will write it very soon and I will share the link here so that the curious readers who want to go into further details of differences between literary theory and literary criticism can enjoy that article. Right now, we will get into other interesting details related to our major topic. Read the detailed article here: Difference between literary criticism and literary theory

Going into the depths of literary theory and literary criticism:

While this is not very wise to get into the depths of the idea called literary theory and criticism for the beginners and ‘early days’ students of English literature , I will give all of you a 360° view of some of the important, also absurd, contributions, interesting facts and complicated ideas related to literary theory. Let’s begin this happening journey:

- The Ambiguity: Applications of literary theories are possible before and after the production of a literary work. Does this idea sound weird? Well, if you consider Aristotle as a literary critic or a literary theorist, you will have to accept that the theories created by him about an ideal tragedy helped many dramatists in Elizabethan age in writing the best-known tragedies. If you consider Longinus and Horace as literary theorists, you will have to admit that their theories in terms of poetry helped many poets in various ages of English literature in producing the poetry of the best possible degree. So, it’s about when any particular theory was propagated and when a literary critic or a writer accesses it and brings into the application. Today, we use theories established the structuralist school, Deconstructionists, Eco-Critical theorists and many others mainly to analyse the text. However, just suppose someone studying any of these theories and modelling a literary work on any of these theories, isn’t that artist using literary theory? He is!

- Literary theory is not only about literature: Yes, get it right now! The domain of literary theory is broad and it does not concern only with literature and literary works. It concerns with human evolution, psychology, philosophy, sociology and language and many other elements (with wide ramifications of this term – elements). The obvious reason is that literature itself is not limited to written works by authors. Literature is an ever-expanding idea and if not ever-expanding, literary theory is also an occasionally expanding idea. Therefore, when you begin studying literary theories, you should be open to facing many ideas that will take you in various directions in terms of academic subjects.

- Science vs Arts or Intellect vs Emotions: Once you begin digging deeper, you will realise that many literary theories have their foundations in the hardcore scientific notions. However, the problem does not lie there. The problem starts when a literary critic implies that all the aesthetic beauty in a poem by John Keats MUST be subdued because he isn’t saying anything new as he is using the same words which have already been repeated more than billion times… won’t you find yourself in a bemused situation? Well, then you realise that anything other than practical criticism method – reading the text closely and not going beyond the paper – is the only best method applicable when analysing literary texts.

As we have had our time with some of the weird ventures into the world of literary theory and criticism, let’s get to the next stage and we will learn the basics of the popular literary theories.

Literary Theories of different types:

Dear readers, now, it’s time to read about types of literary theories. To know more about popular literary theories and their basic introduction, you should read the next article in this series. Click the link below to read it now:

Next article in the series: Types of Literary Theories

This article was written by Alok Mishra for English Literature Education. Alok Mishra is a well-known literary opinion maker, book critic, literary critic and a dedicated literary philanthropist. If you want to join him on his mission to make English Literature easy and freely accessible without the necessary burden of forced interpretations and complicated notions, you can write get in touch with him by visiting his official website: Alok Mishra

Read related articles from this category:

Marxist Theory in Literature: Introduction, Origins, Key Figures, Analysis, Applications & More for English Literature Students

Creative Writing as a Research Method by Jon Cook: Summary and Critical Analysis

Structuralism Theory in English Literature Details of the Structuralist Approach & Key Theorists

Have something to say? Add your comments:

24 Comments . Leave new

Thanks for this amazing article… enjoyed reading it. Helpful and handy for beginners in literary theory studies.

Very helpful article… genuinely impressed. I was confused about literary theory. You have helped me with your easy to understand analysis of this difficult topic for many students. Many thanks.

Wonderful article! Thanks for sharing it! I was totally confused about the concept. I am just a beginner.

I must thank you for this helpful article , literary theory that was very clearly explained that because I’m very happy 😄 thanks 👍 for provide us 😊

Very well done dear Mr. Alok Mishra… The concept ‘literary theory’ is made very clear. The easy & familiar style makes even an average student have a good idea. The other two articles on the subject are also quite enlightening & facilitating for students as well as teachers. Love you…

I must thank you for this helpful article. It helped me understand the very essential meaning of literary theory with its contexts. After reading a few articles, I was confused and almost gave up hope. And then, this site was opened with less hope. Many thanks again sir! I will be a regular reader now. Your writing style is friendly for students. keep up.

Very helpful article! thanks for sharing this. I am an MA student and it helped me understand theory and its purpose.

I liked the way you have presented this article. It helped me a lot with my preparation for the exams at hand.

That’s a wonderful article. I really appreciate the words you have put up here for many to learn and understand literary theory. Keep doing the great job!

This is a very well-explained article! Many thanks for putting such a work online for free.

Very well explained… I was very confused about literary theory until I read this article on this website. This explains the concept aptly and also discusses theories of various kinds in detail in the next articles. Thanks again.

सर शायद विभिन्न स्रोतों से पढ़ने के कारण मैं कन्फ्यूज हो गई हूँ जिससे मैं अभी भी इसे समझ नहीं पा रही हूँ आशा है जल्द ही समझ जाऊँगी

आपका बहुत बहुत धन्यवाद

एक से अधिक स्त्रोतों से अध्ययन में सहायता लेना सर्वथा ही उचित है, अनामिका! यद्यपि, यह अवश्य ध्यान रहे की आप जिन स्त्रोतों का चयन अपने अध्ययन के लिए करती हैं वो उस योग्य हों। तत्पश्चात, यह भी सुनिश्चित करें के आप सर्वप्रथम किसी सर्वमान्य स्त्रोत से इस विषय की प्रारंभिक जानकारी एकत्र करें एवं उसे सम्पूर्णता से समझ लें! आशा है उसके पश्चात आपकी समस्या नहीं रहेगी। इस आलेख को पढ़ने के लिए धन्यवाद!

Thanks very much for your effort, I can say you are almost there. I would like you to please do a video on how to critically analyze a text using any theory ( marxist perspective, ecocriticism, feminisms, negrotudism, post coloniality etc. )

that’s very amazing sir,but sorry!! I want to ask you important question, firstly I’m an English student/student that loves English very plenty but my major problem concerning English is literature in English/literature!! I don’t know how to read a text and find out the settings, and the rest of them,so please can you help me with an ideas of how to find out the settings, plots,and whatsoever?

The part talking about science VS art is hard for me to understand;help plz

honestly speaking, whenever; i need help i look durectly for indins videos and articuls. Guys you

Very much pleased with that explanation

First ,I must say thank you.your View about literay text and techniques are intersting and acceptable.

Hello Sir! I come across with your page and I love your cause of sharing great things about literature. Please allow me to work with you 🙂

Thanks for your message, Mayet! We truly appreciate your wish and you will receive a message from our side very soon. Best wishes!

well done, thanks

I would like to thank the author of this article. I understood what literary theory is and also its differences with literary criticism. The article is written in a simple language and it really helped me. Please write about other literary theories in detail so that I can have a complete idea of different literary theories. thanks again!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

- English Literature

- Short Stories

- Literary Terms

- Web Stories

Literary Theories Simplified For Beginners

Table of Contents

Introduction

Literary Theories Simplified For Beginners For novices in particular, literary theory can frequently seem like an intimidating and complicated subject. It could be challenging to comprehend how literary theories work or why they are important given the diversity of approaches and schools of thinking. But for any student, critic, or fan who wants to interact with literature more deeply, it is essential to comprehend the basic ideas of literary theory.

By dissecting important ideas and offering concise illustrations of their literary applications, this guide aims to make literary theories easier for novices to understand. This article will demystify the various literary theories and explain how each one advances our comprehension of texts, regardless of whether you’re a student learning about literary theory for the first time or someone trying to hone your critical reading abilities.

1. What Is Literary Theory?

Understanding what literary theory is is crucial before delving into the various kinds of literary theories. Scholars and critics utilize literary theory as a collection of frameworks or concepts for interpreting, analyzing, and assessing literature. It gives readers the means to investigate texts’ deeper meanings, comprehend the historical and cultural settings in which they are composed, and evaluate the ideals and ideologies that influence literature.

While literature itself consists of the works—novels, poems, plays, and more—literary theory provides the lenses through which we analyze these works. It helps us move beyond just “what happens” in a text and instead asks questions like “why does this happen?” and “what does this reveal about society, culture, or human nature?”

- Understanding Literary Devices: A Comprehensive Guide

2. Key Literary Theories Explained

Here we will break down some of the most common and influential literary theories, providing simplified explanations and examples for each.

2.1 Formalism (New Criticism)

Overview : Formalism, also known as New Criticism, focuses purely on the text itself, disregarding outside factors such as author biography, historical context, or reader responses. The central idea of formalism is that the text has intrinsic meaning, and this meaning can be uncovered through careful analysis of its structure, language, and literary devices.

Key Features :

- Emphasizes close reading, focusing on the language, imagery, symbolism, and form of the text.

- Investigates how elements like plot structure, rhyme, meter, and narrative techniques contribute to the overall meaning.

Example : A formalist reading of The Great Gatsby might focus on how Fitzgerald’s use of symbolism (such as the green light or the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg) contributes to the novel’s themes of the American Dream and the moral decay of society.

Why It Matters : Formalism highlights the importance of the text itself, encouraging readers to appreciate the literary craft and the power of language.

2.2 Marxist Criticism

Overview : Marxist criticism examines literature through the lens of social class, power dynamics, and economic forces. This theory is based on the ideas of Karl Marx, who argued that all aspects of society—including literature—are influenced by the material conditions of life and the economic structures of the time.

- Focuses on class struggle, the distribution of wealth, and the influence of capitalist systems on social relations.

- Analyzes how texts reflect or challenge social inequalities.

Example : A Marxist reading of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities might explore the divide between the aristocracy and the working class, examining how the novel critiques the oppressive nature of wealth and class hierarchies.

Why It Matters : Marxist criticism reveals the underlying power dynamics in literature, encouraging readers to consider how economic and social factors shape characters and narratives.

2.3 Feminist Criticism

Overview : Feminist criticism examines literature from the perspective of gender, focusing on the roles, representations, and power relations between men and women. This theory is concerned with how literature reflects or perpetuates patriarchal structures and explores how female characters are portrayed.

- Investigates the depiction of women in literature and how gender roles are reinforced or subverted.

- Analyzes the ways in which literature reflects the social and historical contexts of gender.

Example : A feminist reading of Jane Eyre might explore how Charlotte Brontë’s portrayal of the heroine challenges Victorian ideals of femininity and the limitations placed on women in 19th-century society.

Why It Matters : Feminist criticism helps readers identify and question gender biases in literature, while highlighting the importance of diverse and authentic female voices in storytelling.

2.4 Psychoanalytic Criticism

Overview : Psychoanalytic criticism is based on the theories of Sigmund Freud and later psychoanalysts, who suggested that literature can reveal unconscious desires, anxieties, and conflicts. This approach emphasizes the psychological motivations of characters, as well as the author’s subconscious influences.

- Explores the unconscious mind, dreams, repressed memories, and the Oedipus complex.

- Investigates characters’ relationships, especially those that reveal deeper emotional or psychological undercurrents.

Example : A psychoanalytic reading of Hamlet might explore Hamlet’s relationships with his mother, Gertrude, and his father’s ghost, examining the psychological tension that arises from repressed feelings and unresolved grief.

Why It Matters : Psychoanalytic criticism provides a deeper understanding of human behavior, revealing how internal conflicts and desires shape characters and narratives.

2.5 Postcolonial Criticism

Overview : Postcolonial criticism focuses on the effects of colonialism and imperialism on literature and culture. It examines the power dynamics between colonizers and the colonized, often highlighting the struggles of marginalized voices and the legacies of colonial rule.

- Analyzes how colonial powers have shaped the identities, cultures, and histories of colonized peoples.

- Focuses on themes like hybridity, displacement, and resistance.

Example : A postcolonial reading of Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad might explore how the novel reflects colonial exploitation and the dehumanization of both the colonizers and the colonized.

Why It Matters : Postcolonial criticism helps readers understand the lasting impact of colonialism, offering insights into the complexities of cultural identity, power, and resistance.

2.6 Queer Theory

Overview : Queer theory examines literature through the lens of sexuality and gender, focusing on non-normative sexualities and identities. It challenges traditional notions of gender and sexuality, exploring how these concepts are socially constructed and represented in literature.

- Focuses on how LGBTQ+ identities are portrayed in literature.

- Analyzes the fluidity of gender and sexuality and challenges binary thinking (male/female, heterosexual/homosexual).

Example : A queer theory reading of The Picture of Dorian Gray might explore Dorian’s relationships with other men and how his actions subvert conventional ideas of masculinity and sexual identity.

Why It Matters : Queer theory opens up conversations about diverse sexual identities and encourages readers to consider how literature constructs or deconstructs societal norms around gender and sexuality.

3. How to Apply Literary Theories to Texts

Understanding literary theory is one thing; applying it to texts is another. Here’s a simplified guide to help you apply these theories to literature:

3.1 Step 1: Select a Literary Work

Choose a text that interests you. It could be anything from a classic novel to a contemporary poem, depending on your area of focus.

3.2 Step 2: Choose a Literary Theory

Decide which literary theory or theories you’d like to apply. Keep in mind that some texts may lend themselves more easily to certain approaches. For example, a novel focused on class struggle may be ideal for a Marxist reading.

- How To Write A Perfect Literature Essay In 2024

3.3 Step 3: Identify Key Themes and Elements

Seek out plot points, characters, symbols, and themes that relate to the hypothesis. For example, feminist critique focuses on the representation of female characters, whereas psychoanalytic criticism emphasizes the psychological motivations of characters.

3.4 Step 4: Analyze and Interpret

Using the chosen literary theory, analyze the text. Examine how it aligns with the principles of the theory, and interpret the meaning of various literary elements. Make sure to support your interpretations with textual evidence.

3.5 Step 5: Draw Conclusions

Finally, draw conclusions based on your analysis. How does the theory enhance your understanding of the text? How does it shed light on new meanings, themes, or interpretations?

Although it may appear overwhelming at first, literary theory is a vital tool for any serious reader or critic, offering a wide range of tools for analyzing literature. Beginners can interact with texts on a deeper level and learn about the motivations of characters, the social situations in which works were written, and the wider meanings of themes by grasping the fundamentals of various literary theories.

Literary theories are vital resources that provide fresh perspectives on literature, whether you’re reading for enjoyment or getting ready for an academic analysis.

- The Art Of Close Reading: Tips For Students

1. What’s the difference between literary theory and literary criticism?

Literary theory is the framework or lens through which we analyze literature, while literary criticism refers to the actual analysis and interpretation of literary texts. Literary criticism can be guided by literary theory but isn’t limited to it.

2. Can I use more than one literary theory to analyze a text?

Yes, it is possible to use multiple literary theories to analyze a text. In fact, doing so can provide a richer, more nuanced understanding. For example, you could use feminist and postcolonial theories together to analyze a text’s depiction of gender and colonialism.

3. Do I have to agree with the theory I use?

No, you don’t necessarily have to agree with the theory. Literary theories are tools that help us interpret texts, and you can use them to critique and challenge the ideas they present. Feel free to apply the theory critically, while keeping in mind that it’s a lens for analysis, not an absolute truth.

4. How can I know which literary theory to choose for a specific text?

It’s often helpful to consider the themes, context, and characters of the text. For example, if a novel focuses heavily on economic disparities, a Marxist reading might be fitting. If the text addresses issues of identity and gender, a feminist or queer reading could provide valuable insights.

5 . Do I need to know all these literary theories to be a good reader?

While it’s not strictly necessary to be familiar with all literary theories, understanding a few key theories can enhance your reading experience and deepen your understanding of literature. The more theories you explore, the more tools you have to interpret and analyze texts.

- How To Compare And Contrast Two Literary Works

Related Posts

Mmpc-014 financial management solved assignment 2024-25, mmpc-012 strategic management solved assignment 2024-25, mmpc-009 management of machines and materials solved assignment 2024-25.

Attempt a critical appreciation of The Triumph of Life by P.B. Shelley.

Consider The Garden by Andrew Marvell as a didactic poem.

Why does Plato want the artists to be kept away from the ideal state

Do any of the characters surprise you at any stage in the novel Tamas

William Shakespeare Biography and Works

Discuss the theme of freedom in Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

How does William Shakespeare use the concept of power in Richard III

Analyze the use of imagery in William Shakespeare’s sonnets

Mmph-004 industrial and employment relations solved assignment 2024-25, mmph-003 human resource planning solved assignment 2024-25, mmph-002 human resource development solved assignment 2024-25, mmph-001 organisational theory and design solved assignment 2024-25.

- Advertisement

- Privacy & Policy

- Other Links

© 2023 Literopedia

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Are you sure want to unlock this post?

Are you sure want to cancel subscription.

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Literary theory.

“Literary theory” is the body of ideas and methods we use in the practical reading of literature. By literary theory we refer not to the meaning of a work of literature but to the theories that reveal what literature can mean. Literary theory is a description of the underlying principles, one might say the tools, by which we attempt to understand literature. All literary interpretation draws on a basis in theory but can serve as a justification for very different kinds of critical activity. It is literary theory that formulates the relationship between author and work; literary theory develops the significance of race, class, and gender for literary study, both from the standpoint of the biography of the author and an analysis of their thematic presence within texts. Literary theory offers varying approaches for understanding the role of historical context in interpretation as well as the relevance of linguistic and unconscious elements of the text. Literary theorists trace the history and evolution of the different genres—narrative, dramatic, lyric—in addition to the more recent emergence of the novel and the short story, while also investigating the importance of formal elements of literary structure. Lastly, literary theory in recent years has sought to explain the degree to which the text is more the product of a culture than an individual author and in turn how those texts help to create the culture.

Table of Contents

- What Is Literary Theory?

- Traditional Literary Criticism

- Formalism and New Criticism

- Marxism and Critical Theory

- Structuralism and Poststructuralism

- New Historicism and Cultural Materialism

- Ethnic Studies and Postcolonial Criticism

- Gender Studies and Queer Theory

- Cultural Studies

- General Works on Theory

- Literary and Cultural Theory

1. What Is Literary Theory?

“Literary theory,” sometimes designated “critical theory,” or “theory,” and now undergoing a transformation into “cultural theory” within the discipline of literary studies, can be understood as the set of concepts and intellectual assumptions on which rests the work of explaining or interpreting literary texts. Literary theory refers to any principles derived from internal analysis of literary texts or from knowledge external to the text that can be applied in multiple interpretive situations. All critical practice regarding literature depends on an underlying structure of ideas in at least two ways: theory provides a rationale for what constitutes the subject matter of criticism—”the literary”—and the specific aims of critical practice—the act of interpretation itself. For example, to speak of the “unity” of Oedipus the King explicitly invokes Aristotle’s theoretical statements on poetics. To argue, as does Chinua Achebe, that Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness fails to grant full humanity to the Africans it depicts is a perspective informed by a postcolonial literary theory that presupposes a history of exploitation and racism. Critics that explain the climactic drowning of Edna Pontellier in The Awakening as a suicide generally call upon a supporting architecture of feminist and gender theory. The structure of ideas that enables criticism of a literary work may or may not be acknowledged by the critic, and the status of literary theory within the academic discipline of literary studies continues to evolve.

Literary theory and the formal practice of literary interpretation runs a parallel but less well known course with the history of philosophy and is evident in the historical record at least as far back as Plato. The Cratylus contains a Plato’s meditation on the relationship of words and the things to which they refer. Plato’s skepticism about signification, i.e., that words bear no etymological relationship to their meanings but are arbitrarily “imposed,” becomes a central concern in the twentieth century to both “Structuralism” and “Poststructuralism.” However, a persistent belief in “reference,” the notion that words and images refer to an objective reality, has provided epistemological (that is, having to do with theories of knowledge) support for theories of literary representation throughout most of Western history. Until the nineteenth century, Art, in Shakespeare’s phrase, held “a mirror up to nature” and faithfully recorded an objectively real world independent of the observer.

Modern literary theory gradually emerges in Europe during the nineteenth century. In one of the earliest developments of literary theory, German “higher criticism” subjected biblical texts to a radical historicizing that broke with traditional scriptural interpretation. “Higher,” or “source criticism,” analyzed biblical tales in light of comparable narratives from other cultures, an approach that anticipated some of the method and spirit of twentieth century theory, particularly “Structuralism” and “New Historicism.” In France, the eminent literary critic Charles Augustin Saint Beuve maintained that a work of literature could be explained entirely in terms of biography, while novelist Marcel Proust devoted his life to refuting Saint Beuve in a massive narrative in which he contended that the details of the life of the artist are utterly transformed in the work of art. (This dispute was taken up anew by the French theorist Roland Barthes in his famous declaration of the “Death of the Author.” See “Structuralism” and “Poststructuralism.”) Perhaps the greatest nineteenth century influence on literary theory came from the deep epistemological suspicion of Friedrich Nietzsche: that facts are not facts until they have been interpreted. Nietzsche’s critique of knowledge has had a profound impact on literary studies and helped usher in an era of intense literary theorizing that has yet to pass.

Attention to the etymology of the term “theory,” from the Greek “theoria,” alerts us to the partial nature of theoretical approaches to literature. “Theoria” indicates a view or perspective of the Greek stage. This is precisely what literary theory offers, though specific theories often claim to present a complete system for understanding literature. The current state of theory is such that there are many overlapping areas of influence, and older schools of theory, though no longer enjoying their previous eminence, continue to exert an influence on the whole. The once widely-held conviction (an implicit theory) that literature is a repository of all that is meaningful and ennobling in the human experience, a view championed by the Leavis School in Britain, may no longer be acknowledged by name but remains an essential justification for the current structure of American universities and liberal arts curricula. The moment of “Deconstruction” may have passed, but its emphasis on the indeterminacy of signs (that we are unable to establish exclusively what a word means when used in a given situation) and thus of texts, remains significant. Many critics may not embrace the label “feminist,” but the premise that gender is a social construct, one of theoretical feminisms distinguishing insights, is now axiomatic in a number of theoretical perspectives.

While literary theory has always implied or directly expressed a conception of the world outside the text, in the twentieth century three movements—”Marxist theory” of the Frankfurt School, “Feminism,” and “Postmodernism”—have opened the field of literary studies into a broader area of inquiry. Marxist approaches to literature require an understanding of the primary economic and social bases of culture since Marxist aesthetic theory sees the work of art as a product, directly or indirectly, of the base structure of society. Feminist thought and practice analyzes the production of literature and literary representation within the framework that includes all social and cultural formations as they pertain to the role of women in history. Postmodern thought consists of both aesthetic and epistemological strands. Postmodernism in art has included a move toward non-referential, non-linear, abstract forms; a heightened degree of self-referentiality; and the collapse of categories and conventions that had traditionally governed art. Postmodern thought has led to the serious questioning of the so-called metanarratives of history, science, philosophy, and economic and sexual reproduction. Under postmodernity, all knowledge comes to be seen as “constructed” within historical self-contained systems of understanding. Marxist, feminist, and postmodern thought have brought about the incorporation of all human discourses (that is, interlocking fields of language and knowledge) as a subject matter for analysis by the literary theorist. Using the various poststructuralist and postmodern theories that often draw on disciplines other than the literary—linguistic, anthropological, psychoanalytic, and philosophical—for their primary insights, literary theory has become an interdisciplinary body of cultural theory. Taking as its premise that human societies and knowledge consist of texts in one form or another, cultural theory (for better or worse) is now applied to the varieties of texts, ambitiously undertaking to become the preeminent model of inquiry into the human condition.

Literary theory is a site of theories: some theories, like “Queer Theory,” are “in;” other literary theories, like “Deconstruction,” are “out” but continue to exert an influence on the field. “Traditional literary criticism,” “New Criticism,” and “Structuralism” are alike in that they held to the view that the study of literature has an objective body of knowledge under its scrutiny. The other schools of literary theory, to varying degrees, embrace a postmodern view of language and reality that calls into serious question the objective referent of literary studies. The following categories are certainly not exhaustive, nor are they mutually exclusive, but they represent the major trends in literary theory of this century.

2. Traditional Literary Criticism

Academic literary criticism prior to the rise of “New Criticism” in the United States tended to practice traditional literary history: tracking influence, establishing the canon of major writers in the literary periods, and clarifying historical context and allusions within the text. Literary biography was and still is an important interpretive method in and out of the academy; versions of moral criticism, not unlike the Leavis School in Britain, and aesthetic (e.g. genre studies) criticism were also generally influential literary practices. Perhaps the key unifying feature of traditional literary criticism was the consensus within the academy as to the both the literary canon (that is, the books all educated persons should read) and the aims and purposes of literature. What literature was, and why we read literature, and what we read, were questions that subsequent movements in literary theory were to raise.

3. Formalism and New Criticism

“Formalism” is, as the name implies, an interpretive approach that emphasizes literary form and the study of literary devices within the text. The work of the Formalists had a general impact on later developments in “Structuralism” and other theories of narrative. “Formalism,” like “Structuralism,” sought to place the study of literature on a scientific basis through objective analysis of the motifs, devices, techniques, and other “functions” that comprise the literary work. The Formalists placed great importance on the literariness of texts, those qualities that distinguished the literary from other kinds of writing. Neither author nor context was essential for the Formalists; it was the narrative that spoke, the “hero-function,” for example, that had meaning. Form was the content. A plot device or narrative strategy was examined for how it functioned and compared to how it had functioned in other literary works. Of the Russian Formalist critics, Roman Jakobson and Viktor Shklovsky are probably the most well known.

The Formalist adage that the purpose of literature was “to make the stones stonier” nicely expresses their notion of literariness. “Formalism” is perhaps best known is Shklovsky’s concept of “defamiliarization.” The routine of ordinary experience, Shklovsky contended, rendered invisible the uniqueness and particularity of the objects of existence. Literary language, partly by calling attention to itself as language, estranged the reader from the familiar and made fresh the experience of daily life.

The “New Criticism,” so designated as to indicate a break with traditional methods, was a product of the American university in the 1930s and 40s. “New Criticism” stressed close reading of the text itself, much like the French pedagogical precept “explication du texte.” As a strategy of reading, “New Criticism” viewed the work of literature as an aesthetic object independent of historical context and as a unified whole that reflected the unified sensibility of the artist. T.S. Eliot, though not explicitly associated with the movement, expressed a similar critical-aesthetic philosophy in his essays on John Donne and the metaphysical poets, writers who Eliot believed experienced a complete integration of thought and feeling. New Critics like Cleanth Brooks, John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren and W.K. Wimsatt placed a similar focus on the metaphysical poets and poetry in general, a genre well suited to New Critical practice. “New Criticism” aimed at bringing a greater intellectual rigor to literary studies, confining itself to careful scrutiny of the text alone and the formal structures of paradox, ambiguity, irony, and metaphor, among others. “New Criticism” was fired by the conviction that their readings of poetry would yield a humanizing influence on readers and thus counter the alienating tendencies of modern, industrial life. “New Criticism” in this regard bears an affinity to the Southern Agrarian movement whose manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand , contained essays by two New Critics, Ransom and Warren. Perhaps the enduring legacy of “New Criticism” can be found in the college classroom, in which the verbal texture of the poem on the page remains a primary object of literary study.

4. Marxism and Critical Theory

Marxist literary theories tend to focus on the representation of class conflict as well as the reinforcement of class distinctions through the medium of literature. Marxist theorists use traditional techniques of literary analysis but subordinate aesthetic concerns to the final social and political meanings of literature. Marxist theorist often champion authors sympathetic to the working classes and authors whose work challenges economic equalities found in capitalist societies. In keeping with the totalizing spirit of Marxism, literary theories arising from the Marxist paradigm have not only sought new ways of understanding the relationship between economic production and literature, but all cultural production as well. Marxist analyses of society and history have had a profound effect on literary theory and practical criticism, most notably in the development of “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism.”

The Hungarian theorist Georg Lukacs contributed to an understanding of the relationship between historical materialism and literary form, in particular with realism and the historical novel. Walter Benjamin broke new ground in his work in his study of aesthetics and the reproduction of the work of art. The Frankfurt School of philosophers, including most notably Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse—after their emigration to the United States—played a key role in introducing Marxist assessments of culture into the mainstream of American academic life. These thinkers became associated with what is known as “Critical theory,” one of the constituent components of which was a critique of the instrumental use of reason in advanced capitalist culture. “Critical theory” held to a distinction between the high cultural heritage of Europe and the mass culture produced by capitalist societies as an instrument of domination. “Critical theory” sees in the structure of mass cultural forms—jazz, Hollywood film, advertising—a replication of the structure of the factory and the workplace. Creativity and cultural production in advanced capitalist societies were always already co-opted by the entertainment needs of an economic system that requires sensory stimulation and recognizable cliché and suppressed the tendency for sustained deliberation.

The major Marxist influences on literary theory since the Frankfurt School have been Raymond Williams and Terry Eagleton in Great Britain and Frank Lentricchia and Fredric Jameson in the United States. Williams is associated with the New Left political movement in Great Britain and the development of “Cultural Materialism” and the Cultural Studies Movement, originating in the 1960s at Birmingham University’s Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Eagleton is known both as a Marxist theorist and as a popularizer of theory by means of his widely read overview, Literary Theory . Lentricchia likewise became influential through his account of trends in theory, After the New Criticism . Jameson is a more diverse theorist, known both for his impact on Marxist theories of culture and for his position as one of the leading figures in theoretical postmodernism. Jameson’s work on consumer culture, architecture, film, literature and other areas, typifies the collapse of disciplinary boundaries taking place in the realm of Marxist and postmodern cultural theory. Jameson’s work investigates the way the structural features of late capitalism—particularly the transformation of all culture into commodity form—are now deeply embedded in all of our ways of communicating.

5. Structuralism and Poststructuralism

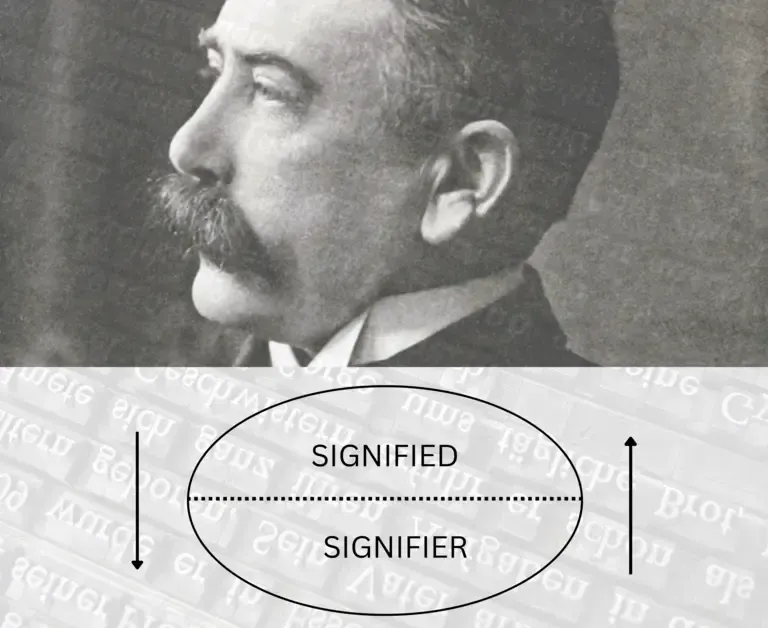

Like the “New Criticism,” “Structuralism” sought to bring to literary studies a set of objective criteria for analysis and a new intellectual rigor. “Structuralism” can be viewed as an extension of “Formalism” in that that both “Structuralism” and “Formalism” devoted their attention to matters of literary form (i.e. structure) rather than social or historical content; and that both bodies of thought were intended to put the study of literature on a scientific, objective basis. “Structuralism” relied initially on the ideas of the Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure. Like Plato, Saussure regarded the signifier (words, marks, symbols) as arbitrary and unrelated to the concept, the signified, to which it referred. Within the way a particular society uses language and signs, meaning was constituted by a system of “differences” between units of the language. Particular meanings were of less interest than the underlying structures of signification that made meaning itself possible, often expressed as an emphasis on “langue” rather than “parole.” “Structuralism” was to be a metalanguage, a language about languages, used to decode actual languages, or systems of signification. The work of the “Formalist” Roman Jakobson contributed to “Structuralist” thought, and the more prominent Structuralists included Claude Levi-Strauss in anthropology, Tzvetan Todorov, A.J. Greimas, Gerard Genette, and Barthes.

The philosopher Roland Barthes proved to be a key figure on the divide between “Structuralism” and “Poststructuralism.” “Poststructuralism” is less unified as a theoretical movement than its precursor; indeed, the work of its advocates known by the term “Deconstruction” calls into question the possibility of the coherence of discourse, or the capacity for language to communicate. “Deconstruction,” Semiotic theory (a study of signs with close connections to “Structuralism,” “Reader response theory” in America (“Reception theory” in Europe), and “Gender theory” informed by the psychoanalysts Jacques Lacan and Julia Kristeva are areas of inquiry that can be located under the banner of “Poststructuralism.” If signifier and signified are both cultural concepts, as they are in “Poststructuralism,” reference to an empirically certifiable reality is no longer guaranteed by language. “Deconstruction” argues that this loss of reference causes an endless deferral of meaning, a system of differences between units of language that has no resting place or final signifier that would enable the other signifiers to hold their meaning. The most important theorist of “Deconstruction,” Jacques Derrida, has asserted, “There is no getting outside text,” indicating a kind of free play of signification in which no fixed, stable meaning is possible. “Poststructuralism” in America was originally identified with a group of Yale academics, the Yale School of “Deconstruction:” J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Hartmann, and Paul de Man. Other tendencies in the moment after “Deconstruction” that share some of the intellectual tendencies of “Poststructuralism” would included the “Reader response” theories of Stanley Fish, Jane Tompkins, and Wolfgang Iser.

Lacanian psychoanalysis, an updating of the work of Sigmund Freud, extends “Postructuralism” to the human subject with further consequences for literary theory. According to Lacan, the fixed, stable self is a Romantic fiction; like the text in “Deconstruction,” the self is a decentered mass of traces left by our encounter with signs, visual symbols, language, etc. For Lacan, the self is constituted by language, a language that is never one’s own, always another’s, always already in use. Barthes applies these currents of thought in his famous declaration of the “death” of the Author: “writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin” while also applying a similar “Poststructuralist” view to the Reader: “the reader is without history, biography, psychology; he is simply that someone who holds together in a single field all the traces by which the written text is constituted.”

Michel Foucault is another philosopher, like Barthes, whose ideas inform much of poststructuralist literary theory. Foucault played a critical role in the development of the postmodern perspective that knowledge is constructed in concrete historical situations in the form of discourse; knowledge is not communicated by discourse but is discourse itself, can only be encountered textually. Following Nietzsche, Foucault performs what he calls “genealogies,” attempts at deconstructing the unacknowledged operation of power and knowledge to reveal the ideologies that make domination of one group by another seem “natural.” Foucaldian investigations of discourse and power were to provide much of the intellectual impetus for a new way of looking at history and doing textual studies that came to be known as the “New Historicism.”

6. New Historicism and Cultural Materialism

“New Historicism,” a term coined by Stephen Greenblatt, designates a body of theoretical and interpretive practices that began largely with the study of early modern literature in the United States. “New Historicism” in America had been somewhat anticipated by the theorists of “Cultural Materialism” in Britain, which, in the words of their leading advocate, Raymond Williams describes “the analysis of all forms of signification, including quite centrally writing, within the actual means and conditions of their production.” Both “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism” seek to understand literary texts historically and reject the formalizing influence of previous literary studies, including “New Criticism,” “Structuralism” and “Deconstruction,” all of which in varying ways privilege the literary text and place only secondary emphasis on historical and social context. According to “New Historicism,” the circulation of literary and non-literary texts produces relations of social power within a culture. New Historicist thought differs from traditional historicism in literary studies in several crucial ways. Rejecting traditional historicism’s premise of neutral inquiry, “New Historicism” accepts the necessity of making historical value judgments. According to “New Historicism,” we can only know the textual history of the past because it is “embedded,” a key term, in the textuality of the present and its concerns. Text and context are less clearly distinct in New Historicist practice. Traditional separations of literary and non-literary texts, “great” literature and popular literature, are also fundamentally challenged. For the “New Historicist,” all acts of expression are embedded in the material conditions of a culture. Texts are examined with an eye for how they reveal the economic and social realities, especially as they produce ideology and represent power or subversion. Like much of the emergent European social history of the 1980s, “New Historicism” takes particular interest in representations of marginal/marginalized groups and non-normative behaviors—witchcraft, cross-dressing, peasant revolts, and exorcisms—as exemplary of the need for power to represent subversive alternatives, the Other, to legitimize itself.

Louis Montrose, another major innovator and exponent of “New Historicism,” describes a fundamental axiom of the movement as an intellectual belief in “the textuality of history and the historicity of texts.” “New Historicism” draws on the work of Levi-Strauss, in particular his notion of culture as a “self-regulating system.” The Foucaldian premise that power is ubiquitous and cannot be equated with state or economic power and Gramsci’s conception of “hegemony,” i.e., that domination is often achieved through culturally-orchestrated consent rather than force, are critical underpinnings to the “New Historicist” perspective. The translation of the work of Mikhail Bakhtin on carnival coincided with the rise of the “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism” and left a legacy in work of other theorists of influence like Peter Stallybrass and Jonathan Dollimore. In its period of ascendancy during the 1980s, “New Historicism” drew criticism from the political left for its depiction of counter-cultural expression as always co-opted by the dominant discourses. Equally, “New Historicism’s” lack of emphasis on “literariness” and formal literary concerns brought disdain from traditional literary scholars. However, “New Historicism” continues to exercise a major influence in the humanities and in the extended conception of literary studies.

7. Ethnic Studies and Postcolonial Criticism

“Ethnic Studies,” sometimes referred to as “Minority Studies,” has an obvious historical relationship with “Postcolonial Criticism” in that Euro-American imperialism and colonization in the last four centuries, whether external (empire) or internal (slavery) has been directed at recognizable ethnic groups: African and African-American, Chinese, the subaltern peoples of India, Irish, Latino, Native American, and Philipino, among others. “Ethnic Studies” concerns itself generally with art and literature produced by identifiable ethnic groups either marginalized or in a subordinate position to a dominant culture. “Postcolonial Criticism” investigates the relationships between colonizers and colonized in the period post-colonization. Though the two fields are increasingly finding points of intersection—the work of bell hooks, for example—and are both activist intellectual enterprises, “Ethnic Studies and “Postcolonial Criticism” have significant differences in their history and ideas.

“Ethnic Studies” has had a considerable impact on literary studies in the United States and Britain. In W.E.B. Dubois, we find an early attempt to theorize the position of African-Americans within dominant white culture through his concept of “double consciousness,” a dual identity including both “American” and “Negro.” Dubois and theorists after him seek an understanding of how that double experience both creates identity and reveals itself in culture. Afro-Caribbean and African writers—Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, Chinua Achebe—have made significant early contributions to the theory and practice of ethnic criticism that explores the traditions, sometimes suppressed or underground, of ethnic literary activity while providing a critique of representations of ethnic identity as found within the majority culture. Ethnic and minority literary theory emphasizes the relationship of cultural identity to individual identity in historical circumstances of overt racial oppression. More recently, scholars and writers such as Henry Louis Gates, Toni Morrison, and Kwame Anthony Appiah have brought attention to the problems inherent in applying theoretical models derived from Euro-centric paradigms (that is, structures of thought) to minority works of literature while at the same time exploring new interpretive strategies for understanding the vernacular (common speech) traditions of racial groups that have been historically marginalized by dominant cultures.

Though not the first writer to explore the historical condition of postcolonialism, the Palestinian literary theorist Edward Said’s book Orientalism is generally regarded as having inaugurated the field of explicitly “Postcolonial Criticism” in the West. Said argues that the concept of “the Orient” was produced by the “imaginative geography” of Western scholarship and has been instrumental in the colonization and domination of non-Western societies. “Postcolonial” theory reverses the historical center/margin direction of cultural inquiry: critiques of the metropolis and capital now emanate from the former colonies. Moreover, theorists like Homi K. Bhabha have questioned the binary thought that produces the dichotomies—center/margin, white/black, and colonizer/colonized—by which colonial practices are justified. The work of Gayatri C. Spivak has focused attention on the question of who speaks for the colonial “Other” and the relation of the ownership of discourse and representation to the development of the postcolonial subjectivity. Like feminist and ethnic theory, “Postcolonial Criticism” pursues not merely the inclusion of the marginalized literature of colonial peoples into the dominant canon and discourse. “Postcolonial Criticism” offers a fundamental critique of the ideology of colonial domination and at the same time seeks to undo the “imaginative geography” of Orientalist thought that produced conceptual as well as economic divides between West and East, civilized and uncivilized, First and Third Worlds. In this respect, “Postcolonial Criticism” is activist and adversarial in its basic aims. Postcolonial theory has brought fresh perspectives to the role of colonial peoples—their wealth, labor, and culture—in the development of modern European nation states. While “Postcolonial Criticism” emerged in the historical moment following the collapse of the modern colonial empires, the increasing globalization of culture, including the neo-colonialism of multinational capitalism, suggests a continued relevance for this field of inquiry.

8. Gender Studies and Queer Theory

Gender theory came to the forefront of the theoretical scene first as feminist theory but has subsequently come to include the investigation of all gender and sexual categories and identities. Feminist gender theory followed slightly behind the reemergence of political feminism in the United States and Western Europe during the 1960s. Political feminism of the so-called “second wave” had as its emphasis practical concerns with the rights of women in contemporary societies, women’s identity, and the representation of women in media and culture. These causes converged with early literary feminist practice, characterized by Elaine Showalter as “gynocriticism,” which emphasized the study and canonical inclusion of works by female authors as well as the depiction of women in male-authored canonical texts.

Feminist gender theory is postmodern in that it challenges the paradigms and intellectual premises of western thought, but also takes an activist stance by proposing frequent interventions and alternative epistemological positions meant to change the social order. In the context of postmodernism, gender theorists, led by the work of Judith Butler, initially viewed the category of “gender” as a human construct enacted by a vast repetition of social performance. The biological distinction between man and woman eventually came under the same scrutiny by theorists who reached a similar conclusion: the sexual categories are products of culture and as such help create social reality rather than simply reflect it. Gender theory achieved a wide readership and acquired much its initial theoretical rigor through the work of a group of French feminist theorists that included Simone de Beauvoir, Luce Irigaray, Helene Cixous, and Julia Kristeva, who while Bulgarian rather than French, made her mark writing in French. French feminist thought is based on the assumption that the Western philosophical tradition represses the experience of women in the structure of its ideas. As an important consequence of this systematic intellectual repression and exclusion, women’s lives and bodies in historical societies are subject to repression as well. In the creative/critical work of Cixous, we find the history of Western thought depicted as binary oppositions: “speech/writing; Nature/Art, Nature/History, Nature/Mind, Passion/Action.” For Cixous, and for Irigaray as well, these binaries are less a function of any objective reality they describe than the male-dominated discourse of the Western tradition that produced them. Their work beyond the descriptive stage becomes an intervention in the history of theoretical discourse, an attempt to alter the existing categories and systems of thought that found Western rationality. French feminism, and perhaps all feminism after Beauvoir, has been in conversation with the psychoanalytic revision of Freud in the work of Jacques Lacan. Kristeva’s work draws heavily on Lacan. Two concepts from Kristeva—the “semiotic” and “abjection”—have had a significant influence on literary theory. Kristeva’s “semiotic” refers to the gaps, silences, spaces, and bodily presence within the language/symbol system of a culture in which there might be a space for a women’s language, different in kind as it would be from male-dominated discourse.