- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Gustav Fechner’s Contributions to Psychology: Pioneering Psychophysics and Beyond

A 19th-century polymath’s groundbreaking work laid the foundation for modern psychology, forever changing how we understand the human mind and perceive the world around us. This visionary thinker was none other than Gustav Theodor Fechner, a German physicist, philosopher, and psychologist whose contributions to the field of psychology continue to shape our understanding of human perception and cognition to this day.

Born in 1801 in a small village in Germany, Fechner’s journey to becoming a pivotal figure in psychology was anything but straightforward. As a young man, he studied medicine at the University of Leipzig, but his insatiable curiosity led him to explore a wide range of disciplines, including physics, mathematics, and philosophy. This diverse background would later prove instrumental in his groundbreaking work in psychology.

Fechner’s era was a time of great intellectual ferment, with the Industrial Revolution in full swing and scientific discoveries reshaping the world. It was against this backdrop of rapid change and innovation that Fechner began to ponder the relationship between the physical world and human perception. His unique blend of scientific rigor and philosophical inquiry would soon give birth to a new field of study: psychophysics.

Fechner’s Psychophysics: The Foundation of Experimental Psychology

Psychophysics, the study of the relationship between physical stimuli and the sensations and perceptions they produce, was Fechner’s brainchild. This revolutionary approach to understanding human perception would go on to become the cornerstone of experimental psychology, paving the way for a more scientific and quantitative study of the mind.

At the heart of Fechner’s psychophysics lies the Weber-Fechner Law, a principle that describes the relationship between the physical magnitude of a stimulus and its perceived intensity. This law, named after Fechner and his predecessor Ernst Weber, states that the just-noticeable difference between two stimuli is proportional to the magnitude of the stimuli.

For example, imagine you’re holding a weight of 100 grams. The Weber-Fechner Law suggests that you’d need to add about 3 grams for you to notice a difference in weight. However, if you were holding a 1000-gram weight, you’d need to add about 30 grams to perceive a change. This principle applies to various sensory modalities, from brightness and loudness to taste and touch.

To investigate these relationships, Fechner developed several ingenious methods of measurement. These included the method of constant stimuli, the method of limits, and the method of adjustment. Each of these techniques allowed researchers to quantify subjective experiences, opening up new avenues for exploring the human mind.

The impact of Fechner’s work on the development of experimental psychology cannot be overstated. His methodical approach to studying perception laid the groundwork for future researchers, including Wilhelm Wundt, who is often credited as the founder of experimental psychology. Wilhelm Wundt’s contributions to psychology were deeply influenced by Fechner’s pioneering work in psychophysics.

The Concept of the Just-Noticeable Difference (JND)

One of Fechner’s most enduring contributions to psychology is the concept of the Just-Noticeable Difference (JND). The JND refers to the minimum amount of change in a stimulus that can be detected by an observer. This concept is fundamental to our understanding of human perception and has far-reaching implications in various fields.

Fechner’s experiments on sensory thresholds were groundbreaking in their approach. He meticulously designed studies to determine the smallest detectable difference in various sensory modalities. For instance, he might ask participants to compare the weights of objects, the brightness of lights, or the pitch of sounds, gradually adjusting the stimuli until the difference became noticeable.

These experiments weren’t just academic exercises; they had real-world applications that continue to influence our lives today. The concept of JND has found its way into consumer research, product design, and even digital technology. Ever wonder why your smartphone’s volume control has more steps at lower volumes than at higher ones? That’s the Weber-Fechner Law and JND in action!

In the realm of consumer psychology, understanding JNDs helps companies determine how much they can change a product without consumers noticing. This could be anything from slightly reducing the size of a chocolate bar to tweaking the formula of a favorite soda. It’s a delicate balance between cost-saving measures and maintaining customer satisfaction.

Fechner’s Elements of Psychophysics

In 1860, Fechner published his magnum opus, “Elements of Psychophysics.” This seminal work laid out the principles of psychophysics in detail and established a new paradigm for psychological research. The book was a tour de force, combining mathematical precision with philosophical depth to create a comprehensive framework for studying the relationship between mind and matter.

“Elements of Psychophysics” introduced several key theories and methods that would become staples of psychological research. Among these was the concept of the psychophysical function, which describes the relationship between the physical intensity of a stimulus and its perceived magnitude. Fechner proposed that this relationship followed a logarithmic function, an idea that, while later refined, still holds significant influence in modern psychophysics.

The book also detailed Fechner’s experimental methods, providing future researchers with a toolkit for investigating sensory perception. These methods, including the aforementioned techniques of constant stimuli, limits, and adjustment, formed the basis for countless studies in the decades that followed.

The influence of “Elements of Psychophysics” on subsequent psychological research cannot be overstated. It sparked a revolution in how psychologists approached the study of perception and cognition. The book’s emphasis on quantitative measurement and experimental rigor set a new standard for psychological inquiry, influencing researchers far beyond the field of psychophysics.

Psychophysics in psychology continues to be a vibrant field of study, with researchers building upon and refining Fechner’s foundational work. From investigations into color perception to studies of pain thresholds, the legacy of “Elements of Psychophysics” lives on in contemporary research.

Fechner’s Philosophy of Mind: Panpsychism

While Fechner is best known for his contributions to experimental psychology, his philosophical ideas were equally profound and forward-thinking. One of his most intriguing philosophical positions was his advocacy for panpsychism, a view that challenges our conventional understanding of consciousness and the mind-body problem.

Panpsychism, in its simplest form, is the idea that consciousness or mind is a fundamental feature of the physical world, present to some degree in all things. This view stands in stark contrast to more mainstream perspectives that see consciousness as emerging solely from complex biological systems like the human brain.

Fechner’s version of panpsychism was nuanced and deeply considered. He argued that just as the physical world exists at various levels of complexity, so too does consciousness. In his view, even the simplest particles might possess some form of rudimentary experience or proto-consciousness. This consciousness, he believed, became more complex and sophisticated as matter organized itself into more complex forms, culminating in the rich inner lives we experience as humans.

This philosophical stance had profound implications for how Fechner approached the mind-body problem – the question of how the mental and physical realms interact. Rather than seeing mind and matter as fundamentally different substances, Fechner proposed that they were two aspects of the same underlying reality. This view, known as dual-aspect monism, offered a novel solution to the centuries-old debate about the nature of consciousness.

Fechner’s panpsychist ideas, while controversial in his time (and still debated today), have had a lasting influence on philosophical and psychological thought. They anticipated later developments in philosophy of mind, including the emergence of neutral monism and the resurgence of interest in panpsychism in contemporary philosophy.

Moreover, Fechner’s willingness to grapple with the hard questions of consciousness and reality exemplifies the interdisciplinary spirit that characterized his work. His approach, bridging empirical science and philosophical inquiry, continues to inspire researchers in fields ranging from cognitive science to quantum physics. Philosophical psychology , a field that seeks to integrate philosophical and psychological perspectives, owes much to Fechner’s pioneering work.

Gustav Fechner’s Lasting Impact on Psychology

Fechner’s enduring legacy in psychology stems from his remarkable ability to integrate philosophy and empirical science. He demonstrated that abstract philosophical questions about the nature of mind and perception could be approached through rigorous scientific inquiry. This synthesis of philosophical depth and scientific precision set a new standard for psychological research.

The influence of Fechner’s work on modern psychophysical methods cannot be overstated. Researchers today continue to use refined versions of his experimental techniques to investigate sensory perception. For instance, signal detection theory, a key tool in modern psychophysics, builds directly on Fechner’s insights about thresholds and just-noticeable differences.

But Fechner’s contributions weren’t limited to perception and psychophysics. He also made significant inroads into the field of aesthetics, applying his quantitative methods to the study of beauty and artistic appreciation. His work in this area laid the groundwork for the empirical study of aesthetics, a field that continues to flourish today.

In cognitive psychology and neuroscience, Fechner’s ideas about the relationship between physical stimuli and mental events continue to resonate. His work laid the foundation for our understanding of how the brain processes sensory information, influencing everything from theories of attention to models of decision-making.

Fechner’s Law in psychology , a refinement of the Weber-Fechner Law, remains a cornerstone of our understanding of sensory perception. It has found applications in fields as diverse as user interface design, audio engineering, and even astrophysics.

Fechner’s approach to psychology was truly revolutionary for his time. He insisted on rigorous measurement and mathematical modeling at a time when many still viewed psychology as a purely philosophical endeavor. This emphasis on quantification and experimentation paved the way for psychology to emerge as a distinct scientific discipline.

Moreover, Fechner’s work bridged the gap between different areas of psychological inquiry. His research touched on perception, cognition, aesthetics, and philosophy of mind, demonstrating the interconnectedness of these fields. This holistic approach to understanding the human mind continues to inspire researchers today, encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration and cross-pollination of ideas.

As we look to the future, Fechner’s legacy continues to shape the direction of psychological research. His emphasis on precise measurement and mathematical modeling has found new relevance in the age of big data and computational neuroscience. At the same time, his philosophical insights into the nature of consciousness and reality continue to inspire new lines of inquiry in cognitive science and philosophy of mind.

Fechner’s work reminds us of the power of interdisciplinary thinking. Just as he drew insights from physics, mathematics, and philosophy to revolutionize psychology, today’s researchers are increasingly crossing disciplinary boundaries to tackle complex questions about the mind and behavior. Sensation psychology , for instance, draws on insights from neuroscience, physics, and cognitive psychology to understand how we perceive the world through our senses.

In conclusion, Gustav Fechner’s contributions to psychology were truly transformative. From laying the foundations of psychophysics to grappling with profound questions about the nature of mind and reality, Fechner’s work continues to shape our understanding of psychology and human experience. His legacy serves as a reminder of the power of curiosity, interdisciplinary thinking, and rigorous scientific inquiry in advancing our understanding of the human mind.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of consciousness and perception, we stand on the shoulders of giants like Fechner. His work not only laid the groundwork for modern experimental psychology but also demonstrated the value of integrating diverse perspectives in the pursuit of knowledge. In an era of increasing specialization, Fechner’s polymathic approach serves as an inspiration for researchers to think broadly and draw connections across disciplines.

The questions Fechner grappled with – about the nature of perception, the relationship between mind and matter, and the quantification of subjective experience – remain at the forefront of psychological and philosophical inquiry today. As we look to the future, Fechner’s work continues to light the way, reminding us of the enduring value of combining philosophical insight with scientific rigor in our quest to understand the human mind.

References:

1. Boring, E. G. (1950). A history of experimental psychology (2nd ed.). Appleton-Century-Crofts.

2. Fechner, G. T. (1860). Elemente der Psychophysik. Breitkopf und Härtel.

3. Gescheider, G. A. (1997). Psychophysics: The fundamentals (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

4. Heidelberger, M. (2004). Nature from within: Gustav Theodor Fechner and his psychophysical worldview. University of Pittsburgh Press.

5. Marshall, M. (2018). The philosopher who helped create the information age. Nature, 555(7695), 167-168. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-02610-0

6. Scheerer, E. (1987). The unknown Fechner. Psychological Research, 49(4), 197-202.

7. Stevens, S. S. (1957). On the psychophysical law. Psychological Review, 64(3), 153-181.

8. Wozniak, R. H. (1999). Classics in Psychology, 1855-1914: Historical Essays. Thoemmes Press.

9. Zöllner, J. K. F. (1872). Über die Natur der Cometen: Beiträge zur Geschichte und Theorie der Erkenntniss. W. Engelmann.

10. Robinson, D. K. (2010). Fechner’s “Inner Psychophysics”. History of Psychology, 13(4), 424-433.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Paul Costa’s Contributions to Psychology: Shaping Personality Research

Psychology Claims: Examining the Most Controversial Theories in Mental Health

Pragnanz Psychology: Simplifying Perception in Gestalt Theory

Carl Jung’s Psychology: Pioneering Concepts and Enduring Contributions

Hans Eysenck’s Contributions to Psychology: Shaping Modern Psychological Theory

Greek Psychology: Ancient Wisdom and Modern Relevance

Parsimony in Psychology: Simplifying Complex Theories and Explanations

Psychology and Philosophy: Exploring the Intersection of Mind and Thought

Philosophical Psychology: Bridging the Gap Between Mind and Behavior

Psychology Museums: Exploring the Human Mind Through Interactive Exhibits

2 minute read

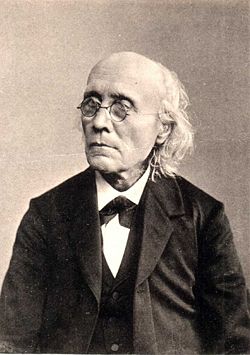

Gustav Theodor Fechner

1801-1887 German experimental psychologist who founded psychophysics and formulated Fechner's law, a landmark in the emergence of psychology as an experimental science.

Gustav Theodor Fechner was born on April 19, 1801, at Gross-Särchen, Lower Lusatia. He earned his degree in biological science in 1822 at the University of Leipzig and taught there until his death on Nov. 18, 1887. Having developed an interest in mathematics and physics, he was appointed professor of physics in 1834.

About 1839 Fechner had a breakdown, having injured his eyes while experimenting on afterimages by gazing at the sun. His response was to isolate himself from the world for three years. During this period there was an increase in his interest in philosophy. Fechner believed that everything is endowed with a soul; nothing is without a material basis; mind and matter are the same essence, but seen from different sides. Moreover, he believed that, by means of psychophysical experiments in psychology, the foregoing assertions were demonstrated and proved. He authored many books and monographs on such diverse subjects as medicine, esthetics, and experimental psychology , affixing the pseudonym Dr. Mises to some of them.

The ultimate philosophic problem which concerned Fechner, and to which his psychophysics was a solution, was the perennial mind-body problem. His solution has been called the identity hypothesis: mind and body are not regarded as a real dualism, but are different sides of

Gustav Fechner ( The Library of Congress . Reproduced with permission.)

one reality. They are separated in the form of sensation and stimulus; that is, what appears from a subjective viewpoint as the mind, appears from an external or objective viewpoint as the body. In the expression of the equation of Fechner's law (sensation intensity = C log stimulus intensity), it becomes evident that the dualism is not real. While this law has been criticized as illogical, and for not having universal applicability, it has been useful in research on hearing and vision .

Fechner's most significant contribution was made in his Elemente der Psychophysik (1860), a text of the "exact science of the functional relations, or relations of dependency, between body and mind," and in his Revision der Hauptpunkte der Psychophysik (1882). Upon these works mainly rests Fechner's fame as a psychologist, for in them he conceived, developed, and established new methods of mental measurement , and hence the beginning of quantitative experimental psychology. The three methods of measurement were the method of just-noticeable differences, the method of constant stimuli, and the method of average error. According to the authorities, the method of constant stimuli, called also the method of right and wrong cases, has become the most important of the three methods. It was further developed by G. E. Müller and F. M. Urban.

William James , who did not care for quantitative analysis or the statistical approach in psychology, dismisses the psychophysic law as an "idol of the den," the psychological outcome of which is nothing. However, the verdict of other appraisers is kinder, for they honor Fechner as the founder of experimental psychology.

Further Reading

Brett, George Sidney. History of psychology. vol. 3. 1921.

Hall, G. Stanley. Founders of modern psychology. 1912.

Klemm, O. History of psychology. 1911. trans. 1914.

Ribot, T. German psychology of today: the empirical school. trans. 1886.

Additional topics

- Hans Juergen Eysenck - Begins career in behavior research, Invites controversy on several fronts

- Gordon Willard Allport - Publishes theory of personality, Examines the nature of prejudice

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Psychology Encyclopedia Famous Psychologists & Scientists

Gustav Fechner, Psychophysics, and the Ultimate Philosophic Problem

Gustav Fechner (1801-1887)

On April 19, 1801 , German philosopher , physicist and experimental psychologist Gustav Theodor Fechner was born. An early pioneer in experimental psychology and founder of psychophysics , he inspired many 20th century scientists and philosophers . He is also credited with demonstrating the non-linear relationship between psychological sensation and the physical intensity of a stimulus , which became known as the Weber–Fechner law .

“Man lives on earth not once, but three times: the first stage of his life is his continual sleep; the second, sleeping and waking by turns; the third, waking forever.” – Gustav Fechner

Gustav Fechner – Early Years

Gustav Fechner was born in Groß Särchen, Lausitz region, Saxonia. The family moved to Dresden in 1815, where Fechner attended the Kreuzschule, but was dismissed after a year and a half with the words: “ You must leave, you can’t learn anything more with us .” So the sixteen-year-old enrolled as a medical student at Leipzig University. He studied physiology with Ernst Heinrich Weber and algebra with Carl Brandan Mollweide , otherwise he remained largely self-taught and was enthusiastic about the natural philosophy of Lorenz Oken . Oken is considered the most important representative of a romantic-speculative natural philosophy. With Isis , Oken published the first interdisciplinary journal in the German-speaking world for over thirty years. On his initiative the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians was founded, which became the model for numerous similar societies.

He Felt Little Talented as a Doctor

In 1819 Fechner became Baccalaureus, in 1823 Magister and private lecturer. He felt little talent as a doctor, especially the practical part of his studies had, according to his own words, “ completely robbed him of his inclination and confidence “. Despite passing his medical exams, he earned his living through literary works. From around 1824 he translated the leading textbooks on physics and chemistry by Jean-Baptiste Biot and Louis Jacques Thénard . In 1828 he was appointed extraordinary professor. In 1833 Fechner married Clara Volkmann and took over the editorial office of the Leipziger Literaturzeitung .

Academic Career

In 1834 , he was appointed professor of physics , however, after contracting an eye disorder, he turned to the study of the mind and its relations with the body, giving public lectures on the subjects dealt with in his books. In 1835 he became the director of the newly opened physics institute, which is considered one of the oldest in Germany. In 1839 he had to give up the physics professorship for health reasons, after his strenuous experiments in galvanism and physiological optics led to an eye disease that made him almost blind. In 1843 he became professor of natural philosophy and anthropology at the University of Leipzig ; he held this post until his death in 1887.

The Identity Hypothesis

Fechner also became increasingly enthusiastic about philosophy and probably the ultimate philosophic problem which concerned him, and to which his psychophysics was a solution , was the perennial mind-body problem . His solution has been called the identity hypothesis. It means that mind and body are not regarded as a real dualism, but are different sides of one reality. They are separated in the form of sensation and stimulus . That is, what appears from a subjective viewpoint as the mind, but it appears from an external or objective viewpoint as the body. In Fechner’s law ( sensation intensity = C log stimulus intensity ), it becomes evident that the dualism is not real. While this law has been criticized as illogical, and for not having universal applicability, it has been useful in research on hearing and vision .

Corpus callosum split

One of Fechner’s speculations about consciousness dealt with brain. During his time, it was known that the brain is bilaterally symmetrical and that there is a deep division between the two halves that are linked by a connecting band of fibers called the corpus callosum . Fechner speculated that if the corpus callosum were split, two separate streams of consciousness would result – the mind would become two. Yet, Fechner believed that his theory would never be tested; he was incorrect. During the mid-twentieth century, Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga worked on epileptic patients with sectioned corpus callosum and observed that Fechner’s idea was correct.

The principle of the uniform linkage of the manifold

Man has an innate need for variety. But the alternation must be connected by something, must show a unity. The longer the occupation with an object lasts, the higher should be its manifoldness, in order not to become boring. A manifoldness that has no unity is perceived as chaotic. The relation of single parts to each other can be very simple (like in a circle, where each part behaves exactly the same to the other parts) or highly complex. A single (even complete) interruption of a uniformity is its strongest disturbance, a stain on a white dress interrupts the continuous white. A regular interruption can compensate for and even exceed the disruption of the interruption by its regularity. Thus, most people prefer complex patterns to empty spaces. The more varied a thing is, the stronger the aesthetic sensation will be, provided a unity is perceived. If the unity is missing, one sees a chaos, which one cannot gain anything from. The higher the mental ability to perceive and process complex things, the greater the desire for them, and the faster boredom sets in with simple structures.

The aesthetic principle of association

“One finds an orange more beautiful than an appropriately painted wooden ball” – this is how Fechner explains the principle of association. The sensual eye may perceive the same thing, but the mental eye sees a lot more in the orange, such as the refreshing taste, but also the country of origin, and one’s own ideas regarding this country and its culture (summer, sunshine, sea, vacation, friendly people, etc.). What the sensory eye perceives (the direct impression) can be in harmony or in contradiction with what is associated. The older and more experienced a person is, the more the memories (associations) tend to override the actual experience. Young people, on the other hand, are far more impressionable. Depending on the experiences already gathered, associative demands are also made on new things. If these requirements are fulfilled, a feeling of unanimity occurs. If they are not fulfilled, we feel a contradiction.

Psychophysics

Honors and later years.

In January 1830 he founded the Chemisches Zentralblatt together with the publisher Leopold Voß. In 1846 Fechner was co-founder of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences in Leipzig. In 1859 Fechner was elected a member of the scholarly society Leopoldina . In 1873 Fechner was awarded an honorary doctorate in medicine, and in 1884 he was made an honorary citizen of the city of Leipzig. Little is known of Fechner’s later years, nor of the circumstances, cause, and manner of his death in 1887.

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Gustav Fechner Biography

- [2] “Gustav Fechner – German psychologist and physicist” . Encyclopedia Britannica .

- [3] Gustav Fechner Biography, Bibliography, and sources

- [4] Gustav Fechner at Wikidata

- [5] Gustav Fechner at Reasonator

- [6] Works by or about Gustav Fechner at Internet Archive

- [7] Gustav Theodor Fechner, (1904) The Little Book of Life after Death

- [8] Immanuel Kant – Philosopher of the Enlightenment , SciHi Blog

- [9] Wilhelm Wundt – Father of Experimental Psychology , SciHi Blog

- [10] Hermann von Helmholtz – Physiologist and Physicist , SciHi Blog

- [11] Heidelberger, M. (2001), “Gustav Theodor Fechner” in Statisticians of the Centuries (ed. C. C. Heyde and E. Seneta) pp. 142–147. New York: Springer Verlag, 2001.

- [12] Gustav Theodor Fechner, (1908), The Living Word

- [13] Michael Billing, The Billig Lectures (Lectures 12&13) , ‘Historical and Conceptual Issues’, 2012, DARGchive @ youtube

- [14] Timeline of Experimental Psychologists , via DBpedia and Wikidata

Tabea Tietz

Related posts, emmy noether and the love for mathematics, carsten niebuhr and the decipherment of cuneiform, karl friedrich schinkel and the prussian city scapes, august leopold crelle and his journal.

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #45 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #37 | Whewell's Ghost

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Further Projects

- February (28)

- January (30)

- December (30)

- November (29)

- October (31)

- September (30)

- August (30)

- January (31)

- December (31)

- November (30)

- August (31)

- February (29)

- February (19)

- January (18)

- October (29)

- September (29)

- February (5)

- January (5)

- December (14)

- November (9)

- October (13)

- September (6)

- August (13)

- December (3)

- November (5)

- October (1)

- September (3)

- November (2)

- September (2)

Legal Notice

- Privacy Statement

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Gustav theodor fechner: psychophysics and natural science.

- David K. Robinson David K. Robinson Truman State University, Department of History

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.487

- Published online: 31 March 2020

Gustav Theodor Fechner (b. 1801–d. 1887) is well known to psychologists as the founder of psychophysics, a set of methods for empirically relating measured sensory stimulus to reported sensation. Rich as this field of research has proven to be, especially as detection instruments and recording devices have improved in modern times, Fechner himself would be disappointed to discover that he is remembered merely for psychophysics as psychologists understand it today. To Fechner, those particular methods and approaches were only one part of the domain of psychophysics—outer psychophysics—whereas he envisioned psychophysics (both outer and inner) to be the key to the broadest kind of scientific worldview: the study of the relationship between the material world and the mental world (indeed the spiritual universe; in German, die geistige Welt ).

The preface of Fechner’s 1860 masterwork, Elements of Psychophysics , states, “[I]t is an exact theory of the relation of mind to body. . . . As an exact science psychophysics, like physics, must rest on experience and the mathematical connection of those empirical facts that demand a measure of what is experienced or, when such a measure is not available, a search for it.” In that definition, Fechner reveals his view of natural science, and how psychophysics was meant to expand the range of natural science and the scope of its achievements. Fechner’s influence emerged during the mid-19th century, as the physical and medical sciences were achieving great breakthroughs and establishing fundamental and unifying concepts; this was especially true in Germany, including the city where he came to study and remained for the rest of his life, Leipzig. Fechner was one of the most enthusiastic and optimistic believers in unifying concepts of science.

Fechner’s psychophysics gave important impetus to psychometrics and experimental psychology; he also proposed a statistical approach to aesthetics and a “theory of collectives” that pointed toward statistical interpretations of many (perhaps all) areas of experience. In his early career he was a central figure in German physics and an early supporter of the atomic theory of matter as well as Darwinian evolution. His profoundly spiritual ideas, however, were out of step with the science of his time. This aspect of Fechner’s thought is evident in his inner psychophysics, where he searched for the full measure of “what is experienced.”

- psychophysics

- inner psychophysics

- quantitative methods

- philosophy of science

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 22 December 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|91.193.111.216]

- 91.193.111.216

Character limit 500 /500

Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Remote Ready Biology Learning Activities

Resources for Teaching about Coronavirus has descriptions and links for multiple resources to use in teaching and learning about coronavirus.

Remote Ready Biology Learning Activities has 50 remote-ready activities, which work for either your classroom or remote teaching.

- brain & behavior

- complex systems

- science education

- science & culture

- art exhibitions

3. Mind, Brain, and the Experimental Psychology of Consciousness

Citation: Wozniak, Robert H. " Mind and Body: Rene Déscartes to William James " http://serendipstudio.org/Mind/; Bryn Mawr College, Serendip 1995 Originally published in 1992 at Bethesda, MD & Washington, DC by the National Library of Medicine and the American Psychological Association. | Forum | Guest Exhibitions | Serendip Home |

Gustav Fechner

Gustav Theodor Fechner (April 19, 1801 – November 28, 1887) was a German psychologist who invented psychophysics, laying the foundation for the development of experimental psychology. Fechner's goal was to develop scientific techniques that would measure the relationship between the mental activity of the mind , and the physical behavior of the body, which he believed to be connected like two sides of the same coin. He was also interested in art and made significant contributions to our understanding of aesthetic principles. Fechner inspired many 20th century scientists and philosophers, including Ernst Mach , Wilhelm Wundt , Sigmund Freud , and G. Stanley Hall .

- 4 Major Publications

- 5 References

- 6 External links

While his founding insights have stimulated much fruitful subsequent research regarding the relation between body and mind, Fechner's particular attempts to define a precise formula relating strength of the stimulus and the strength of the sensation were highly controversial and generally rejected. Nonetheless, his place in history is secured because his work did open the door to the objective study of mental activity, a key development toward gaining psychology a place in the spectrum of scientific disciplines.

Gustav Theodor Fechner was born in a small village at Gross-Särchen, Prussia ( Germany ). The son of a Lutheran pastor, he was taught Latin from the age of five years. His father died when he was still a young boy. Fechner attended the Gymnasium in Sorau and Dresden, and in 1817 he enrolled at the University of Leipzig, in the city where he spent the rest of his life.

Fechner received his medical degree in 1822, but decided not to practice medicine . Instead, he started to write satire, under the pseudonym of Dr. Mises. Through this he criticized contemporary German society, especially its predominantly materialistic worldview.

At the same time, Fechner began to study physics. In 1824 he started giving lectures, and in 1834 was appointed professor of physics at the University of Leipzig. He married in 1833.

Fechner contracted an eye disorder in 1839 due to long periods he had spent staring into the sun while studying the phenomenon of after-images. After much suffering, Fechner resigned his professorship. The following period of Fechner’s life was rather grim, marked with suffering from near blindness, and thoughts about suicide . Eventually however, Fechner overcame his problems and recovered in the early 1840s. In 1844 he received a small pension from the university, which enabled him to continue to live and study on his own. In 1848 he returned to the university as a professor of philosophy .

The problems with his sight led Fechner to turn toward more speculative and metaphysical studies. He started research on the mind and its relation to the body. In 1850 Fechner experienced a flash of insight about the nature of the connection between mind and body. Based on this insight he created psychophysics—the study of the relationship between stimulus intensity and subjective experience of the stimulus.

In 1860 he published his great work, Elemente der Psychophysik (Elements of Psychophysics) , which opened doors for him into the academic community. In the late 1860s and 1870s, however, Fechner's interest turned to the study of the aesthetic principles of art. He even conducted something that seems to have been the first public opinion poll when he invited the public to vote on which of two paintings was more beautiful. Fechner published his famous Vorschule der Aesthetik in 1876, in which he explained some basic principles of aesthetics. However, he never lost interest in research on the relationship between mind and body, and he continued his work in this area. Fechner spent the rest of his life giving public lectures, until his death in 1887.

Fechner's epoch-making work was his Elemente der Psychophysik in which he elaborated on Spinoza 's thought that bodily facts and conscious facts, though not reducible one to the other, are different sides of one reality. Fechner tried to discover an exact mathematical relationship between mind and body. The most famous outcome of his inquiries was the law that became known as Weber's or Fechner's law. It may be expressed as follows:

Though holding good only within certain limits, this law has been found immensely useful. Unfortunately, from the success of this theory, showing that the intensity of a sensation increases by definite increases of stimulus, Fechner was led to postulate the existence of a unit of sensation, so that any sensation might be regarded as composed of units. His general formula for deriving the number of units in any sensation is expressed as

where S stands for the sensation, R for the stimulus numerically estimated, and c for a constant that must be separately determined by experiment in each particular order of sensibility.

Fechner's conclusions have been criticized on several levels, but the main critics were the “structuralists” who claimed that although stimuli are composite, sensations are not. "Every sensation," wrote William James , "presents itself as an indivisible unit; and it is quite impossible to read any clear meaning into the notion that they are masses of units combined." Still, the idea of the exact measurement of sensation has been a fruitful one, and mainly through his influence on Wilhelm Wundt , Fechner became the "father" of the "new" laboratories of psychology investigating human faculties with the aid of precise scientific apparatus. If sensations, Fechner argued, could be represented by numbers, then psychology could become an exact science , susceptible to mathematical treatment.

Fechner also studied the still-mysterious perceptual illusion of "Fechner color," whereby colors are seen in a moving pattern of black and white. He published numerous papers in the fields of chemistry and physics, and translated works of Jean-Baptiste Biot and Louis-Jacques Thénard from French. A different, but essential, side of his character can be seen in his poems and humorous pieces, such as the Vergleichende Anatomie der Engel (Comparative Anatomy of Angels) (1825), written under the pseudonym of "Dr. Mises." Fechner's work in aesthetics was also important. He conducted experiments to show that certain abstract forms and proportions are naturally pleasing to our senses , and provided new illustrations of the working of aesthetic association.

Although he was quite influential in his time, disciples of his general philosophy were few. His world concept was highly animistic —he felt the thrill of life everywhere, in plants , earth , stars , the total universe . He saw human beings as standing midway between the souls of plants and the souls of stars, who are angels . God , the soul of the universe, must be conceived as having an existence analogous to men. Natural laws are just the modes of the unfolding of God's perfection. In his last work, Fechner, aged but full of hope, contrasted this joyous "daylight view" of the world with the dead, dreary "night view" of materialism .

Fechner's position in reference to his predecessors and contemporaries is not very sharply defined. He was remotely a disciple of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling , learnt much from Johann Friedrich Herbart and Christian Hermann Weisse, and decidedly rejected Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and the monadism of Rudolf Hermann Lotze .

As the pioneer in psychophysics, he inspired many twentieth century scientists. Before Fechner, there was only "psychological physiology" and "philosophical psychology." Fechner’s experimental method began a whole new wave in psychology, which became the basis for experimental psychology. His techniques and methods inspired Wilhelm Wundt , who created the first scientific study of conscious experience, opening the door to the scientific study of mind .

Major Publications

- Fechner, Gustav T. 2005 (original 1836). Das Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tod . Weiser Books. ISBN 1578633338

- Fechner, Gustav T. 1992 (original 1848). Nanna, oder über das Seelenleben der Pflanzen . D. Klotz. ISBN 388074971X

- Fechner, Gustav T. 1851. Zendavesta, oder über die Dinge des Himmels und des lenseits .

- Fechner, Gustav T. 1853. Uber die physikalische und philosophische Atomenlehre .

- Fechner, Gustav T. 1998 (original 1860). Elemente der Psychophysik . Thoemmes Continuum. ISBN 1855066572

- Fechner, Gustav T. 1876. Vorschule der Ästhetik .

- Fechner, Gustav T. 1879. Die Tagesansicht gegenüber der Nachtansicht .

References ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Heidelberger, M. 2001. "Gustav Theodor Fechner" in Statisticians of the Centuries (C. C. Heyde et al, eds.) pp. 142-147. New York: Springer. ISBN 0387953299

- Stigler, Stephen M. 1986. The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty before 1900 . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 067440341X

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition , a publication now in the public domain .

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2024.

- Elements of Psychophysics - An extract from Elements of Psychophysics

- Introduction to Elemente der Psychophysik . - An introduction by Robert H. Wozniak

- Kleine Schriften - Fechner - Biography in German

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards . This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Gustav_Fechner history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia :

- History of "Gustav Fechner"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- Psychologists

- Pages using ISBN magic links

COMMENTS

Nov 14, 2024 · Gustav Fechner (born April 19, 1801, Gross Särchen, near Muskau, Lusatia [Germany]—died November 18, 1887, Leipzig, Germany) was a German physicist and philosopher who was a key figure in the founding of psychophysics, the science concerned with quantitative relations between sensations and the stimuli producing them.

Sep 15, 2024 · While Fechner is best known for his contributions to experimental psychology, his philosophical ideas were equally profound and forward-thinking. One of his most intriguing philosophical positions was his advocacy for panpsychism, a view that challenges our conventional understanding of consciousness and the mind-body problem.

Gustav Theodor Fechner (/ ˈ f ɛ x n ər /; German:; 19 April 1801 – 18 November 1887) [1] was a German physicist, philosopher, and experimental psychologist. A pioneer in experimental psychology and founder of psychophysics (techniques for measuring the mind ), he inspired many 20th-century scientists and philosophers.

German experimental psychologist who founded psychophysics and formulated Fechner's law, a landmark in the emergence of psychology as an experimental science. Gustav Theodor Fechner was born on April 19, 1801, at Gross-Särchen, Lower Lusatia.

Apr 19, 2020 · Along with Wilhelm Wundt and Hermann von Helmholtz, Gustav Fechner is recognized as one of the founders of modern experimental psychology. His clearest contribution was the demonstration that because the mind was susceptible to measurement and mathematical treatment, psychology had the potential to become a quantified science.

Jun 8, 2018 · The German experimental psychologist Gustav The odor Fechner (1801-1887) founded psychophysics and formulated Fechner's law, a landmark in the emergence of psychology as an experimental science. Gustav Theodor Fechner was born on April 19, 1801, at Gross-Särchen, Lower Lusatia.

Fechner was one of the most enthusiastic and optimistic believers in unifying concepts of science.Fechner’s psychophysics gave important impetus to psychometrics and experimental psychology; he also proposed a statistical approach to aesthetics and a “theory of collectives” that pointed toward statistical interpretations of many (perhaps ...

3. Mind, Brain, and the Experimental Psychology of Consciousness It is in the work of Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801-1887) that we find the formal beginning of experimental psychology. Before Fechner, as Boring (1950) tells us, there was only psychological physiology and philosophical psychology.

history of scientifical psychology . Introduction Even though Fechner did not call himself a psychologist, some important historians of psychology like Edwin G. Boring consider the experimental rising of this science in Fechner’s work (1979, p.297). More specifically, it was Fechner’s famous intuition of October 22, 1850

Gustav Theodor Fechner (April 19, 1801 – November 28, 1887) was a German psychologist who invented psychophysics, laying the foundation for the development of experimental psychology. Fechner's goal was to develop scientific techniques that would measure the relationship between the mental activity of the mind , and the physical behavior of ...