Certification for Growth

Scaling up Fairtrade Cocoa Traceability and Data Management to 25 Coops in Côte d’Ivoire

Fairtrade started more than 30 years ago to enable farmers and workers to have more control over their lives and invest in a sustainable future. Fairtrade certifies cocoa and other products that meet rigorous social, economic, and environmental standards, from farm to shelf. Farmers and workers benefit from Fairtrade’s Minimum Price and Premium guarantees, as well as standards, training, and support on topics from gender equality to climate change adaptation, to good agricultural practices and crop diversification. When it comes to the food supply chain, the foundation adamantly supports cooperatives, acknowledging their potential to improve smallholder farmers’ livelihoods. Beyond farming practices, Fairtrade believes democratic, transparent, and participative cooperatives can be powerful economic and political aggregators that can respond to their members’ needs and manage their business operations effectively.

Since 2019, the Fairtrade Cocoa Standard requires all Fairtrade-certified coops to implement an Farmforce Origin (IMS). Such systems collect data on members’ farms, production, and sales, and enable them to manage risks such as deforestation. The ability to track the purchased cocoa from each member’s farm is essential to ‘first mile’ traceability. The aim of the Farmforce Origin requirement was to promote cooperatives’ collection and ownership of their own data in one place and to enable them to better track and manage risks, which in turn meets commercial partners’ information needs. In addition, having detailed member and sales information can help cooperatives to access bank loans.

However, while training a few African coops in the lead-up to Farmforce Origin implementation, Fairtrade came across some issues. Although the cooperatives were learning how to use an IMS, they were not fully integrating the system into their data collection and storage practices. Most coops were still loosely recording information on spreadsheets or even on paper. Coops were also collecting an enormous amount of data for other third parties, such as NGOs, government entities, traders, and other certification bodies, usually each with different systems. Even when the cooperatives had set up their IMS and integrated all their data into it, the managers were not conducting much data analysis.

That is when Fairtrade turned to Farmforce to forge a partnership. The aim was to have a system where coops-maintained ownership of their data, increasing their cocoa traceability while collecting information that helps reduce risks such as deforestation and child labor.

In 2020, we started a pilot project with three Fairtrade-certified cocoa cooperatives in Côte d’Ivoire, providing our supply chain management software as a service (SaaS). The initial pilot was also supported by the local software implementation organization, Think! Data Services . As of May 2022, Farmforce and Fairtrade are scaling the project up to a further twenty-five cooperatives.

Learnings From the Pilot Phase: Engaging the Coop Team Is key

One of the pilot’s main takeaways was that coop’s senior leadership must be fully committed to the project to make Farmforce Origin a success. This is achieved if coop managers are made aware of and appreciate the following:

- Farmforce Origin rollout will take staff time but it will also save time in the medium run-through efficiency

- The long-term opportunities implied by Farmforce digitalization

- Farmforce cost-effectiveness since the first year of implementation (funded by Fairtrade)

We also set up a centralized mailbox for coops to request assistance whenever needed. This will also be used in phase 2 and will be complemented in the first eighteen months by intensive in-person support from Farmforce and Fairtrade. This will maximize coop managers’ engagement in the crucial early months and help us nurture long-term relationships with them.

In order to better reinforce expertise on-site, we introduced a superuser concept at each coop. Superusers are often more tech-savvy and receive specific training so they can help coop colleagues familiarize themselves with the technology, and serve as a link between Fairtrade, Farmforce, and the coop.

The Time Is Ripe For Ramping Up

Since the pilot phase, the need for coops to have a digitalized IMS has grown even further. The evolving regulatory landscape in Europe on Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence and deforestation means that coops will need to manage more complex data and risk analysis to continue selling their cocoa on the European market–which farmers are reliant on for their livelihoods. The Farmforce system enables coops to have the digital capacity to manage this data.

The Fairtrade-Farmforce partnership expansion will now see an additional twenty-five cooperatives engaged with the Farmforce system, with nearly 400 people trained on how to use the software for optimizing efficiency for the cooperatives and their members.

In line with the pilot phase, we have selected an eclectic mix of coops to boost our learnings through this journey. Scaling up will not necessarily be easy, but we are working hard to minimize the challenges. For example, Farmforce has developed a standardized IMS configuration that could be adapted to any of the 25 Ivorian coops engaged in phase 2. Together with the pilot cooperatives, Think! Data, and Fairtrade, we have crafted data templates to speed up the upload of coop-specific datasets. In addition, we have designed a Farmforce Academy (FFA) program to streamline our training campaign.

“Because of the logistics challenges, an extensive and high-quality training on the solution will be really beneficial to our cooperative for collecting the information needed, streamlining our certification process, and accessing new markets,” Louis Sosthene B., trainee from the Coop CA ECAPR., said. “Considering the increasing stakes in the sector and the upcoming stricter regulations, digitizing our farms is a step we need to take to improve our activity and the living conditions of the producers.”

“Our primary mission during this scale-up phase is to ensure that the involved cooperatives are enabled to use Farmforce effectively, leading to long-term benefits for their businesses and for their members,” says Jon Walker, Fairtrade’s Senior Advisor for Cocoa. “Ultimately, the focus for us is to ensure greater efficiency in cooperative management based on the principles of Fair Data, or the implementation of fairness in data distribution and ownership.”

Fairtrade changes the way trade works through better prices, decent working conditions, and a fairer deal for farmers and workers in developing countries. Fairtrade International is an independent non-profit organization representing 1.9 million small-scale farmers and workers worldwide. It owns the FAIRTRADE Mark, a registered trademark of Fairtrade that appears on more than 30,000 products. Beyond certification, Fairtrade International and its member organizations empower producers, partner with businesses, engage consumers, and advocate for a fair and sustainable future.

At Farmforce, food’s first mile is our passion. Our SaaS solutions provide organizations with the confidence to secure sustainable sourcing, improve farmers’ quality of life and protect the environment. We turn data into tools, which means more vetted acres, more measurable impact on communities, more financial opportunities for farmers, and more clarity for customers. We believe in building a better food supply where it starts. Farmforce customers span 28 countries across Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. With over nine years of experience now managing over 735,000+ farmers in 27 crop value chains in 15 languages on our platform. A continuous loop of innovation with our customers in the center of food’s first mile journey.

Free Insightful Analysis and Trends for Your First Mile

I am not interested in this free resource.

e.l.f. Beauty and Fair Trade USA™ Case Study

A partnership case study, a beauty first.

In 2022, e.l.f. and Fair Trade USA worked together to create a brand new framework for beauty industry factories to become Fair Trade Certified™, with e.l.f. being the first in the beauty industry to source from a Fair Trade Certified™ factory. The announcement of this certification was welcomed with enthusiasm as it demonstrates the range of products that can be Fair Trade Certified and represents an important addition to the already impressive portfolio of ethical and sustainable sourcing practices adopted by e.l.f. – a company dedicated to social impact and doing good.

e.l.f. and Sustainability

e.l.f. was founded with a mission to bring the best of beauty to every eye, lip, and face. e.l.f. uniquely brings premium quality products at an extraordinary value, that are clean, vegan, and cruelty free. e.l.f. is also committed to its purpose of standing with every eye, lip, face, paw, and fin – creating a culture internally—and in the world—where all individuals are encouraged to express their truest selves and are empowered to succeed. e.l.f. never tests on animals and is proudly 100% cruelty free worldwide, achieving double-certified “cruelty-free” status from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and Leaping Bunny across all of its brands.

In fiscal year 2022, e.l.f. advanced its packaging sustainability strategies—eliminating to date more than one million pounds of excess packaging since the inception of “Project Unicorn,” and setting a new goal for 100% of its paper cartons to be Forest-Stewardship Council (FSC)-certified by FY 2025. The company also completed its first measurement of greenhouse gas emissions to establish a baseline toward future environmental strategy development.

The Fair Trade Journey

e.l.f.’s priority of doing the right thing, for the people, the planet and its furry and finned friends, includes many of the commitments mentioned above. It also extends to doing the right thing for its third-party manufacturers and their teams .

The journey to Fair Trade began long before Chairman and CEO Tarang Amin took the helm of e.l.f. Beauty when he was introduced to Fair Trade USA Founder and CEO, Paul Rice, by a mutual friend. They became trusted advisors to one another, sharing their goals and vision for their work. When Tarang joined e.l.f., becoming Fair Trade Certified continued to be on Tarang’s mind. The obvious conversation began: could Fair Trade USA’s factory program, which had been historically focused on apparel and home goods, work in beauty?

After visiting several Fair Trade Certified factories together, the answer Tarang and Paul came to was “yes.” Both came away impressed by the positive impact on the workers’ morale, the state of the factories, and their productivity. Fair Trade USA’s ability to marry a rigorous, impactful standard with established consumer recognition and preference for the Fair Trade Certified label in the market also signaled to e.l.f that certification was well worth the investment.

Tarang shared:

“Consumers love e.l.f. because of our superpowers. We bring premium quality products at an extraordinary value that are cruelty free, vegan, and clean, and now we are adding one more superpower: achieving Fair Trade Certified factories.”

It is important to e.l.f. to understand the impact of each step of its product development and supply chain, and the company utilizes a number of initiatives to increase its positive impact from a sustainability and environmental perspective. Fair Trade Certified allows e.l.f. to reach deeper into the supply chain to benefit the people behind the products that they bring to market.

“It’s been very meaningful to partner with Fair Trade USA to establish the first Fair Trade Certification in the beauty industry for our third-party manufacturers,” Tarang furthers. “We look forward to growing consumer awareness and education around Fair Trade practices to make a difference in communities around the world.”

Once the intent to work with Fair Trade USA was solidified, the next steps involved mapping out implementation, which required collaboration and collective problem-solving.

Neha Gohil, Vice President of Global Sourcing and Strategic Extensions explained, “We were excited to partner with Fair Trade USA to establish the framework for the first cosmetics-production in their factory program. We knew it would not only set a new standard at e.l.f. but for the entire beauty industry in hopes that it will become widely adopted across the sector. We started the certification process before the pandemic, yet when COVID hit, there were many obstacles that hadn’t existed in the past – for instance getting auditors onsite to learn more about makeup and cosmetics manufacturing. Our team was able to quickly pivot and focus on sharing insights and industry standards virtually. Once we got the first factory certified we got into a rhythm. Everyone started to understand what kinds of questions needed to be asked and how to best coach and partner with workers and management to make sure everyone was aligned on what the priorities were and what the standard needed to cover. From then on, we have been able to move with efficiency – and now we hope for other beauty companies to follow our lead.”

The results have been affirming. Tarang shared that the company has been working with their factories for years to make sure that there are good working conditions, protections, and oversight; however, now e.l.f.’s customers know that there is a third party confirming and strengthening those efforts. He added that, “We wanted to show that we can do this, we can do it right, we can do it fairly, and in a way that uplifts and supports the workers at these factories.”

Neha added:

“Fair Trade also improves our suppliers’ overall sustainability scorecards because they now have formalized documentation and processes in place due to earning their Fair Trade Certification.”

Fair Trade USA’s Approach to Innovation

Fair Trade USA is building an innovative model of responsible business, conscious consumerism, and shared value to eliminate poverty and enable sustainable development for farmers, workers, their families, and communities around the world. Innovation is driven by market actors who are committed to sourcing Fair Trade Certified products if they are, or can be, available. This approach ensures that there are buyers for the products coming from farms, fisheries, or factories should they choose to make the investment in achieving Fair Trade Certification.

The organization is committed to continuously improving this model and identifying opportunities to expand reach and impact through business partnerships and through the expertise, technologies, and resources provided by philanthropic partners.

Fair Trade USA’s standards are rigorous and sometimes require significant changes in the way that producer groups are organized, resourced, and where they are focused on making improvements. Without a demand from the market, those investments of time, staff, and funds would not deliver on the promise that Fair Trade offers.

With a motivated, collaborative partner like e.l.f. Beauty providing that market partnership, there was excitement to explore how the model could deliver on its promise to workers in cosmetics factories. With over a decade of experience in the factory sector, Fair Trade USA’s program has both grown and evolved since 2012. The inclusion of factories producing home goods in addition to apparel gave the organization an important understanding of how to make sure that processes, standards, and implementation could be agile enough to maintain rigor while also accommodating different types of factory production.

Standards Innovation

As a credible standard-setting organization who is an ISEAL Code Compliant member , Fair Trade USA follows best practices in monitoring and evolving its standards. Those best practices include transparently conducting regular revisions of standards in close concert with key stakeholders.

The work with e.l.f. provided a timely inflection point for the organization to consider whether a minor or major revision would be most useful to deliver the most benefit to factory workers, and, if so, how to best optimize our program to unlock more opportunity for scale with a broader range of industries and brands.

That led to undertaking a major revision that resulted in the Factory Production Standard (FPS) 2.0. Goals of this revision included maintaining the rigor of onboarding and implementation while increasing the efficiency and speed of bringing factories into the program. Prior to the revision, certification and onboarding of Fair Trade Certified factories could take 6 months or more, leading to longer timelines for workers to start receiving program benefits and brands to be able to bring certified products to market.

The revised standard has already broadened the range of products that can come from Fair Trade Certified factories, including footwear and beauty, and will extend the benefits of Fair Trade to workers in even more supply chains. It will also allow factories in more countries to become Fair Trade Certified.

Fair Trade USA’s vision is for all programs to maintain their rigor and impact while also bringing the efficiency, transparency, and data analytics needed to scale. Another critical element of being part of ISEAL is including stakeholder input, public consultation, and human rights due diligence.

The revised standard has already broadened the range of products that can come from Fair Trade Certified factories, including footwear and beauty, and will extend the benefits of fair trade to workers in even more supply chains. It will also allow factories in more countries to become Fair Trade Certified.

The FPS 2.0 benefitted from extensive stakeholder input gathered through:

- Pre-consultation interviews to reflect on program successes, challenges, and opportunities.

- A series of factory and brand webinars that provided a forum for initial reaction and feedback to the draft FPS 2.0.

- A Worker Engagement Survey, which garnered input from over 3,400 workers from 13 Fair Trade Certified factories.

- On- and offline comment forms made available to the public for 3 months; and,

- Individual consultations with auditing bodies, research institutions, and peer certification schemes.

Stakeholder feedback was largely positive and provided concrete suggestions for ways to improve the content and overall impact of the standard. The importance of trainings for factories, workers, and auditing bodies was emphasized as were some concerns about the standard’s complexity and density. This feedback resulted in simplification of requirements, timelines, and more straightforward scoring and compliance models. Additionally, a new policy was created to maintain program rigor and transparency in factories operating in shared buildings – an innovation that directly facilitated expansion into new beauty facilities and will open the door for a broader range of products to be included in the Fair Trade movement.

Once the FPS was finalized, Fair Trade USA moved to implementation which included:

- Training field staff on the different production realities of cosmetics products.

- Developing two new pre-audit assessments to prepare factories for Year 0 (entry) requirements and identify any additional risks; and,

- Launching a series of worker surveys that include a Year 0 baseline survey completed before entering the program, a second survey using the same questions after Premium funds have been received, and then annual surveys to understand evolving benefits of the program and any new needs or areas for improvement.

Sending Signals to the Sector

Both e.l.f. and Fair Trade USA have great enthusiasm and high hopes for the life-changing impact that sourcing from Fair Trade Certified beauty factories promises for the workers in those factories. By launching with such a leading brand in the sector, the two organizations hope to send a message to companies across both the beauty industry and the larger factory-sourcing sector that doing good is good business.

Building a truly sustainable product array is only possible when including social, economic, and environmental sustainability along with other areas of focus like packaging and animal welfare. e.l.f. is proof that major brands and companies can quickly make and deliver on significant volume commitments to jump start their sustainability performance and benefit from consumer recognition and preference for the Fair Trade Certified label.

This is possible and achievable in the beauty sector. It is also possible and achievable for all products manufactured in factories.

e.l.f. and Fair Trade USA™ Partnership Case Study

Would you like to download this case study? Click the link below!

Learn More about Fair Trade Factories

Fair trade factory program.

Our Factory Program upholds rigorous social, economic, and environmental standards.

Our Standards

Review the Fair Trade Certified Factory Production Standard (FPS) 2.0 and Trade Standard to learn more.

Start Your Fair Trade Journey

Learn how Fair Trade USA’s award-winning, rigorous, and globally recognized sustainable sourcing certification program can transform your business!

NBC Nightly News features Fairtrade cocoa farmers!

Cocoa farmers in West Africa are the backbone of the chocolate industry, but climate change is increasingly affecting their crops. Learn how Daniel and Ataa are adapting in collaboration with Fairtrade.

Impact Stories

Fairtrade is global. We work with nearly 2 million farmers and workers in the Global South and 2,400+ committed brands are selling Fairtrade certified products around the world. We are proud to share the stories of people, cooperatives and businesses that are all dedicated to creating a more just world through trade.

All Stories

Climate Action in Cocoa

Daniel, Ghanaian cocoa farmer

Solomon Boateng

A Q&A with Deborah Osei-Mensah

Sankara Azéta

Coliman Bananas– family-owned, farmer-focused

Fairtrade, Mars and ECOOKIM partner to raise farmer incomes

You’re on the list

We have received your email sign-up. Please tell us more so we can deliver tailored content to your inbox!

Thank you for subscribing.

We are so excited to share more about Fairtrade with you. You’ll be hearing from us soon!

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Global Issues

The problem with fair trade coffee fetchandinjecthtml('/defer-load/edit-this/2534', document.currentscript);.

Fair Trade-certified coffee is growing in consumer familiarity and sales, but strict certification requirements are resulting in uneven economic advantages for coffee growers and lower quality coffee for consumers. By failing to address these problems, industry confidence in Fair Trade coffee is slipping.

- download https://ssir.org/pdf/2011SU_CaseStudy_Haight.pdf

- order reprints

- related stories

By Colleen Haight Summer 2011

Peter Giuliano is in many ways the model of a Fair Trade coffee advocate. He began his career as a humble barista, worked his way up the ladder, and in 1995 co-founded Counter Culture Coffee, a wholesale roasting and coffee education enterprise in Durham, N.C. In his role as the green coffee buyer, Giuliano has developed close working relationships with farmers throughout the coffee-growing world, traveling extensively to Latin America, Indonesia, and Africa. He has been active for more than a decade in the Specialty Coffee Association of America, the world’s largest coffee trade association, and currently serves as its president.

Giuliano originally embraced the Fair Trade-certification model—which pays producers an above-market “fair trade” price provided they meet specific labor, environmental, and production standards—because he believed it was the best way to empower growers and drive the sustainable development of one of the world’s largest commodities. Today, Giuliano no longer purchases Fair Trade-certified coffee for his business. “I think fair trade as a concept is very relevant,” says Giuliano. But “I think the Fair Trade-certified FLO model is not relevant at all and kind of never has been, because they were doing something different than they were selling to the consumer. … That’s exactly why I left TransFair [now Fair Trade USA]. They’re selling a different thing than they’re producing.”

Giuliano is among a growing group of coffee growers, roasters, and importers who believe that Fair Trade-certified coffee is not living up to its chief promise to reduce poverty . Retailers explain that neither FLO—the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International umbrella group—nor Fair Trade USA , the American standards and certification arm of FLO, has sufficient data showing positive economic impact on growers. Yet both nonprofits state that their mission is to “use a market-based approach that empowers farmers to get a fair price for their harvest, helps workers create safe working conditions, provides a decent living wage, and guarantees the right to organize.” 1 (In this article, the term Fair Trade coffee refers to coffee that has been certified as “Fair Trade” by FLO or Fair Trade USA; the term Fair Trade refers to the certification model of FLO and Fair Trade USA; and the term fair trade refers to the movement to improve the lives of growers and other producers through trade.)

FLO rules cover artisans and farmers who produce not just coffee but also a variety of goods, including tea, cocoa, bananas, sugar, honey, rice, flowers, cotton, and even sports balls. Its certification process requires producing organizations to comply with a set of minimum standards “designed to support the sustainable development of small-scale producers and agricultural workers in the poorest countries in the world.” 2 These standards—31 pages of general and product-specific standards—detail member farm size, electoral processes and democratic organization, contractual transparency and reporting, and environmental standards, to name only a few. Supporting organizations, such as Fair Trade USA, in Oakland, Calif., ensure that the product is properly handled, labeled, and marketed in the consuming country.

Like many economic and political movements, the fair trade movement arose to address the perceived failure of the market and remedy important social issues. As the name implies, Fair Trade has sought not only to protect farmers but also to correct the legacy of the colonial mercantilist system and the kind of crony capitalism where large businesses obtain special privileges from local governments, preventing small businesses from competing and flourishing. To its credit, Fair Trade USA has played a significant role in getting American consumers to pay more attention to the economic plight of poor coffee growers. Although Fair Trade coffee still accounts for only a small fraction of overall coffee sales, the market for Fair Trade coffee has grown markedly over the last decade, and purchases of Fair Trade coffee have helped improve the lives of many small growers.

Despite these achievements, the system by which Fair Trade USA hopes to achieve its ends is seriously flawed, limiting both its market potential and the benefits it provides growers and workers. Among the concerns are that the premiums paid by consumers are not going directly to farmers, the quality of Fair Trade coffee is uneven, and the model is technologically outdated. This article will examine why, over the past 20 years, Fair Trade coffee has evolved from an economic and social justice movement to largely a marketing model for ethical consumerism—and why the model persists regardless of its limitations.

The Origins of Fair Trade

The idea of fair trade has been around since people first started exchanging goods with one another. The history of trade has shown, however, that exchange has not always been fair. The mercantile system that dominated Western Europe from the 16th to the late 18th century was a nationalistic system intended to enrich the state. Businesses, such as the Dutch East India Company, operating for the benefit of the mother country in “the colonies,” were afforded monopoly privileges and protected from local competition by tariffs. Under these circumstances, trade was anything but fair. Local workers often were compelled through force—slavery or indentured servitude—to work long hours under terrible conditions. In the 1940s and 1950s, nongovernmental and religious organizations, such as Ten Thousand Villages and SERRV International, attempted to create supply chains that were fair to producers, mostly creators of handicrafts. In the 1960s, the fair trade movement began to take shape, along with the criticism that industrialized countries and multinational corporations were using their power for further enrichment to the detriment of poorer counties and producers, particularly of agricultural products like coffee.

Adding to these perceived economic imbalances is the cyclical nature of the coffee business. As an agricultural product that is sensitive to growing conditions and temperature fluctuations, coffee is subject to exaggerated boom-bust cycles. Booms occur when farm output is low, causing price increases due to limited supply; bust cycles occur when there is a bumper crop, causing price declines due to large supply. Price stabilization is an objective commonly sought by less-developed countries through commodity agreements. Thus the International Commodity Agreement (ICA) evolved as a means to stabilize the chronic price fluctuations and endemic instability of the coffee industry. The first of these agreements arose in the 1940s to provide stability during wartime, when the European markets were unavailable to Latin American producers.

After the war, a boom in coffee demand made renewal of the agreement unnecessary. But during the late 1950s, down cycles threatened economies once again. The ICA essentially was little more than a cartel agreement between the member countries (coffee producers) to restrict output during bust periods to maintain higher prices, storing the surplus beans to sell later when output was low. Because the US government was concerned about the spread of communism in Latin America, it supported the cartel by enforcing import restrictions. In 1989, however, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the waning of communist influence, the United States lost interest in supporting the agreement and withdrew. Without US enforcement, the cartel fell prey to rampant cheating on the part of its members and eventually dissolved. Attempts have since been made to resurrect the cartel—but though it exists in name, it remains largely ineffective.

Recognizing the dire circumstances confronting farmers during the late 1980s, when the price of coffee once again plunged, fair trade activists formulated a system whereby farmers could obtain access to international markets and reasonable reward for their labor. In 1988 a coalition of those economic justice activists created the first fair trade certification initiative in the Netherlands, called Max Havelaar, after a fictional Dutch character who opposed the exploitation of coffee farmers by Dutch colonialists in the East Indies. The organization created a label for products that met certain wage standards. Other similar organizations arose within Europe, eventually merging in 1997 to create FLO, based in Bonn, Germany, which today sets the Fair Trade-certification standards and serves to inspect and certify the producer organizations.

Why do we care about fairly traded coffee? One reason is the importance of coffee to the economies of the countries in which the crop is grown. Coffee is the second most valuable commodity exported from developing countries, petroleum being the first. For many of the world’s least developed countries, such as Honduras, Ethiopia, and Guatemala, coffee exports make up an enormous share of the export earnings, comprising in some cases more than 50 percent of foreign exchange earnings. 3 In addition, many of the coffee growers are small and their businesses are financially marginal.

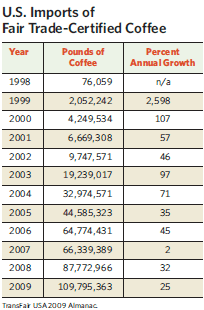

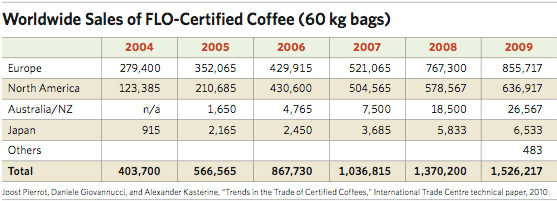

Although some of the world’s poorest countries produce coffee, the preponderance of that production is consumed by the citizens of the world’s wealthiest countries. The United States is the world’s single largest consuming country, buying more than 22 percent of world coffee imports; the combined countries of the European Union import roughly 67 percent, 4 with other countries importing the remaining 10 percent. According to the Specialty Coffee Retailer, an industry resource site, specialty coffee in 2010 accounted for $13.65 billion in sales, one-third of the nation’s $40 billion coffee industry. The Specialty Coffee Association of America reports that approximately 23 million people in the United States drink specialty or gourmet coffee daily. Fair Trade coffee, which has grown steadily from 76,059 pounds in 1998 to 109,795,363 pounds in 2009, 5 constitutes only about 4 percent of that $14 billion market.

The primary way in by which FLO and Fair Trade USA attempt to alleviate poverty and jump-start economic development among coffee growers is a mechanism called a price floor, a limit on how low a price can be charged for a product. As of March 2011, FLO fixed a price floor of $1.40 per pound of green coffee beans. FLO also indexes that floor to the New York Coffee Exchange price, so that when prices rise above $1.40 per pound for commodity, or non-specialty, coffee, the Fair Trade price paid is always at least 20 cents per pound higher than the price for commodity coffee.

Commodity coffee is broken into grades, but within each grade the coffee is standardized. This means that beans from one batch are assumed to be identical to those in any other batch. It is a standardized product. Specialty coffee, on the other hand, is sold because of its distinctive flavor characteristics. Because specialty coffees are of a higher grade, they command higher prices. Fair Trade coffee can come in any quality grade, but the coffee is considered part of the specialty coffee market because of its special production requirements and pricing structure. It is these requirements and pricing structure that create a quality problem for Fair Trade coffee.

To understand how the problem arises, one must understand that the low consumer demand for Fair Trade coffee means that not all of a particular farmer’s coffee, which will be of varying quality, may be sold at the Fair Trade price. The rest must be sold on the market at whatever price the quality of the coffee will support.

A simple example illustrates this point. A farmer has two bags of coffee to sell and there is a Fair Trade buyer for only one bag. The farmer knows bag A would be worth $1.70 per pound on the open market because the quality is high and bag B would be worth only $1.20 because the quality is lower. Which should he sell as Fair Trade coffee for the guaranteed price of $1.40? If he sells bag A as Fair Trade, he earns $1.40 (the Fair Trade price) and sells bag B for $1.20 (the market price), equaling $2.60. If he sells bag B as Fair Trade coffee he earns $1.40, and sells bag A at the market price for $1.70, he earns a total of $3.10. To maximize his income, therefore, he will choose to sell his lower quality coffee as Fair Trade coffee. Also, if the farmer knows that his lower quality beans can be sold at $1.40 per pound (provided there is demand), he may decide to increase his income by reallocating his resources to boost the quality of some beans over others. For example, he might stop fertilizing one group of plants and concentrate on improving the quality of the others. Thus the chances increase that the Fair Trade coffee will be of consistently lower quality. This problem is accentuated when the price of coffee rises to 30-year highs, as it has done recently.

One of the unique characteristics of the FLO and Fair Trade USA model is that only certain types of growers can qualify for certification—specifically, small growers who do not rely on permanent hired labor and belong to democratically run cooperatives. This means that private estate farmers and multinational companies like Kraft or Nestlé that grow their own coffee cannot be certified as Fair Trade coffee, even if they pay producers well, help create environmentally sustainable and organic products, and build schools and medical clinics for grower communities.

Although the cooperative requirement may seem unusual, it follows logically from the experience of Paul Rice, founder and president of Fair Trade USA. Rice spent most of the early 1980s working with cooperative farmers in Latin America, studying and implementing training programs for small farmer organizations on behalf of the Nicaragua Agrarian Reform Ministry under the Sandinista administration. In 1990, he became the first CEO of prodecoop, a fair trade organic cooperative representing almost 3,000 small coffee farmers in northern Nicaragua. Then in 1998, he founded Fair Trade USA. Rice sees cooperatives as the key to the empowerment of the independent coffee farmer, providing a union-like type of collective bargaining power that enables cooperative leaders to negotiate pricing for the individual members.

Membership in a cooperative is a requirement of Fair Trade regulations. Another core element is the premium—the subsidy (now 20 cents per pound) paid by purchasers to ensure economic and environmental sustainability. Premiums are retained by the cooperative and do not pass directly to farmers. Instead, the farmers vote on how the premium is to be spent for their collective use. They may decide to use it to upgrade the milling equipment of a cooperative, improve irrigation, or provide some community benefit, such as medical or educational facilities.

Fair Trade USA is a nonprofit, but an unusually sustainable one. It gets most of its revenues from service fees from retailers. For every pound of Fair Trade coffee sold in the United States, retailers must pay 10 cents to Fair Trade USA. That 10 cents helps the organization promote its brand, which has led some in the coffee business to say that Fair Trade USA is primarily a marketing organization. In 2009, the nonprofit had a budget of $10 million, 70 percent of which was funded by fees. The remaining 30 percent came from philanthropic contributions, mostly from foundation grants and private donors.

People in the coffee industry find it hard to criticize FLO and Fair Trade USA, because of its mission “to empower family farmers and workers around the world, while enriching the lives of those struggling in poverty” and to create wider conditions for sustainable development, equity, and environmental responsibility. 6 “I’m hook, line, and sinker for the Fair Trade mission,” says Shirin Moayyad, director of coffee purchasing for Peet’s Coffee & Tea Inc. “When I read [the statement], I thought, there’s nothing I disagree with here. Everything here I believe in.” Yet Moayyad has concerns about the effectiveness of the model, mostly because she does not see FLO making progress toward those goals.

Whole Foods Market initially rejected the Fair Trade model. The supermarket chain only recently began buying Fair Trade coffee, through its private label coffee, Allegro, in response to the demand from their consumers. Jeff Teter, president of Allegro Coffee, a specialty coffee business begun in 1985 and sold to Whole Foods in 1997, said that his main concern has been the quality of Fair Trade coffee. “To get great quality coffee, you pay the market price. Now, in our instance, it’s a lot more than what the Fair Trade floor prices are,” he says. As for social justice for coffee growers, Teter responds: “We were living the model at least 10 years before Paul Rice and TransFair people got started here in America. … Paul Rice and his group have done an amazing job convincing a small group of vocal and active consumers in America to be suspicious of anybody who isn’t FT.” Rice disagrees, arguing, “Fair Trade is the only certification program today that ensures and proves that farmers are getting more money.”

An Imperfect Model

My field and analytical research has found that there are distinct limitations to the Fair Trade model. 7 Perhaps the most serious challenge is the extraordinarily high price of coffee. “The market today is five times higher than when FLO entered the United States. The market’s at $2.50 (per pound for commodity coffee) today vs. the 40 cents or 50 cents (per pound) it was at in 2001,” says Dennis Macray, former director of global sustainability at Starbucks Coffee Co. This price shift dampens farmers’ desire to sell their high-quality coffee at the Fair Trade price. Many co-ops, according to Macray, are choosing to default on the Fair Trade contracts, so that they can do better for their members by selling on the open market. Macray, who is now an independent sustainability consultant with clients such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, says the default problem is seriously compounded by the perceptions of quality. Some roasters express concern that the quality of Fair Trade coffee is not at the same high levels as other types of specialty coffee sold alongside it. “For some cooperatives the Fair Trade price became the ceiling, not the floor. … Many Fair Trade buyers do not see a reason why they should pay any more than the fair trade price for the value that is Fair Trade,” explains Macray.

In the past, coffee growers were often isolated in remote regions and had little access to market information on the value of their product. Unscrupulous buyers might offer only very low prices, taking advantage of farmers’ lack of information. Today, however, growers have access to coffee price fluctuations on their cell phones and, in many cases, have a keener understanding of how to negotiate with foreign distributors to get the best price per pound. In addition, the growing demand for very high quality coffee has led to a tremendous increase in the number of buyers traveling to more remote regions to ensure the supply they require.

Another important flaw is FLO’s inability to alter the circumstances of the poorest of the poor in the coffee farming community. Although FLO does dictate certain minimal labor standards, such as paying workers minimum wage and banning child labor, the primary focus and beneficiary is the small farmer, who, in turn, is defined as a small landowner. The poorest segment of the farming community, however, is the migrant laborer who does not have the resources to own land and thus cannot be part of a cooperative. In Costa Rica, for example, most small farms, including those selling Fair Trade coffee, employ migrant laborers for harvesting, particularly from Nicaragua and Panama. Rice believes that because the “yields are so low on a small farm and it’s basically family run, the migrant labor issue is not as relevant.” But at the same time he admits that the benefits of Fair Trade do not reach migrant laborers; he says he wants to expand the model to serve this population.

Rice has never wavered from his view that Fair Trade’s “central goal is to alleviate poverty,” and he is adamant that the organization’s model is as relevant as it was 20 years ago. But during that time many of FLO’s provisions of have become duplications of regulations already in place in Latin American countries, such as minimum wage requirements, credit financing, and contracting terms. “I just don’t think that the benefits are trickling down,” says Philip Sansone, president and executive director of the Whole Planet Foundation (the philanthropic arm of Whole Foods). Rice disagrees and defends his model. “The small holders in Latin America would have no way of climbing out of poverty,” he says. “One-acre farmers standing alone are pretty much always going to be victimized by stronger market forces, be they middlemen or moneylenders. At those farm unit sizes and yields, no one is viable in the global market if they stand alone.”

Another challenge for FLO is the issue of transparency in business dealings. FLO regulations require a great amount of record keeping, to ensure that individual farmers have access to all information pertaining to the cooperative’s sales and farming practices, enabling them to make more informed business and agricultural decisions. But this record keeping has proven to be a hurdle in some cases. In addition to being time-consuming, it has also raised language and literacy barriers. Certification forms, for example, only recently were made available in Spanish. “They want a record to be kept of every daily activity, with dates and names, products, etc. They want everything kept track of. The small producers, on the other hand, can hardly write their own name,” 8 said Jesus Gonzales, a farmer at Tajumuco Cooperative in Guatemala. Records kept by cooperatives have shown that premiums paid for Fair Trade coffee are often used not for schools or organic farming but to build nicer facilities for cooperatives or to pay for extra office staff. Gerardo Alberto de Leon, manager of Fedecocagua, the largest cooperative in Guatemala selling Fair Trade coffee, told me during my 2006 field research, “The premium we use here [at the cooperative]—you saw our coffee lab, it is very professional.”

Although the cooperative lab may improve quality or sales or aid in member education, it is not necessarily where consumers who buy Fair Trade coffee think their money is going. Macray says coffee consumers want to know that the extra premiums are being used for social services. “Many licensees have started to question whether the premiums were being used for social good: schools, education, health, nutrition, and so on,” he says. “It became difficult to tell the story of where that premium was going. So in your retail shop, you want to be able to tell your customers, yeah, how we provide all this extra funding for these co-ops and it made these differences.”

FLO also provides incentives for some farmers to remain in the coffee business even though the market signals that they will not be successful. If a coffee farmer’s cost of production is higher than he is able to obtain for his product, he will go out of business. By offering a higher price, Fair Trade keeps him in a business for which his land may not be suitable. There are areas all over Latin America and Africa where the climate and growing conditions are simply not conducive to coffee growing. “Fair Trade directs itself to organizations and regions where there is a degree of marginality,” explains Eliecer Ureña Prado, dean of the School of Agricultural Economics at the University of Costa Rica. “We’re talking about unfavorable climates [for coffee production]. … Regions that are not competitive.”

The Future of Fair Trade Coffee

The FLO model has changed little since its inception. Although the Fair Trade price and premium for coffee has been adjusted upward over time, the rules and regulations have remained fairly static. Fair Trade’s chief legacy may be greater consumer awareness among coffee drinkers. “We generate awareness to create demand in the market,” explains Stacy Wagner, public relations manager at Fair Trade USA. And they have had tremendous success doing so. Today, according to Wagner, 50 percent of American households are aware of Fair Trade coffee, up from only 9 percent in 2005.

Representatives from Starbucks, Peet’s, and Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (which owns such brands as Caribou Coffee, Tully’s, and Newman’s Own) all report a push from consumers for more transparency of contract and socially responsible business practices. It is rare to find a coffee roaster or retailer these days that does not address social issues in some way. Some do so by offering Fair Trade coffee. Others, however, have sought out other solutions, such as adopting other certifications or by developing their own programs. “A number of importers and exporters in the coffee business are saying we can get more money into the pockets of farmers through direct trade than if we use the FLO model,” says Macray.

Examples of businesses that have risen to meet consumer demands include Starbucks, Peet’s, and Whole Foods’ Allegro coffee. Although Starbucks offers Fair Trade coffee as one of a number of options, they also have put into place a C.A.F.E. Practice—a program that defines socially responsible business guidelines for their buyers. Many coffee producers have taken note of this model and made their practices more sustainable to attract the attention of Starbucks’ buyers. Likewise, Peet’s buys a lot of coffee from TechnoServe , an organization working to improve the business practices of farmers in developing countries. “One of the objections to Fair Trade could be that the term ‘cooperative’ doesn’t perforce equate to ‘farmer,’” says Moayyad. “Just because a certain price is guaranteed to the cooperative, doesn’t actually mean that the farmer is receiving it.”

With TechnoServe, farmers get a much higher percentage of the proceeds—up to 60 percent more according to Moayyad, even though their stated focus is “developing entrepreneurs, building businesses and industries, and improving the business environment.” 9 TechnoServe’s model focuses on quality production and farm management. “It’s not a charity,” says Jim Reynolds, roast master emeritus of Peet’s, who has more than 30 years of buying experience. “It’s building skills and better business organization, so they can run their own co-ops more efficiently and earn better pricing by finding good buyers.” Teter also follows this type of socially responsible corporate investment. Allegro pays well above the Fair Trade price to obtain the quality coffees its customers want. In addition, 5 percent of Allegro’s profits goes to charity, and 85 percent is spent in growers’ communities.

“The model for sustainable coffee that was popular five years ago has changed quite a bit,” says Macray. “Five years ago, it was common practice to just go out and buy certified coffees and check the box; and today it’s about integrating sustainability and transparency into your supply chain. Companies are making it a core way of doing business.”

For more on Fair Trade:

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Colleen Haight .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

- Postdoctoral Scholars

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

- Faculty Recruiting

- See All Jobs

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Initiative for Financial Decision-Making

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Webinars

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Past Scholars

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Subscribe to Corporate Governance Emails

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

Fair Trade USA, Innovating for Impact

- Research & Insights

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Annual Alumni Dinner

- Class of 2024 Candidates

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Marketing

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- Career Change

- Career Advancement

- Career Support and Resources

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Program Contacts

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Laura Bunch

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- RKMA Market Research Handbook Series

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Media centre

- Resources library

- Campaign materials

Programmes case studies

The Fairtrade Foundation has identified five key themes, underpinned by our Theory of Change , where we are working with pioneering businesses to make trade fair.

The Fairtrade Standards offer a broad set of principles which we believe are the bedrock of future, more sustainable trade. There are over 1.65 million farmers and workers in 1,210 producer organisations across the Fairtrade system and the impact that the Standards have is well known.

However, we also recognise that leading organisations will identify specific areas where they can go deeper to address the sustainability issues specific to them, whether that’s mitigating a particular environmental issue, securing a supply chain or because their suppliers come from a particularly vulnerable or marginalised group. This will be driven by their assessment of materiality within their sustainability programmes, seeking out where their activities have a significant impact.

Providing direct support to producer organisations

Deepening commitment by going beyond compliance can help increase the long-term developmental impact of commercial partners’ work. This can include investing in organisations they source from in a number of areas:

- Providing technical support

- Providing specific thematic support

- Providing routes to access credit

- Facilitating strategic partnerships

- Providing marketing support for producers

- Helping producers move up the value chain.

Case Study: Matthew Algie and M&S – Brewing benefits with coffee farmers in Ethiopia

Case Study: Waitrose – Raising a cup to quality coffee in Brazil

Case Study: Palestinian Almonds – Creating a buzz about Palestinian Almonds

Case Study: A Programme Partnership to Create More Resilient Flower Supply Chains

Preferential sourcing

Fairtrade is also about creating routes to market from disadvantaged regions or marginalised groups and their organisations who would not otherwise have access through conventional trading routes. This involves:

- Understanding the profile of farmers

- Understanding how to benefit the most vulnerable

- Sourcing directly from smallholder farmers and their organisations

- Sourcing from conflict zones or climatically challenging regions

- Product-specific preferential sourcing from particular groups of farmers from particular regions in specific products

- Building new supply chains in new products.

Buying practices

The balance of power in supply chains is often with large traders, businesses and retailers and not with small farmers or their organisations. Buyers are often the first point of contact for small-scale farmers in the chain and can play an important role in improving terms of trade and transparency through:

- Entering into longer-term and stable contracts

- Regular contact with farmers/their organisations

- Regular feedback to farmers on product quality and ‘emotional traceability’

- Transparent and regular price and contract negotiations

- Fair risk-sharing

- Timely cash payments throughout the year, rather than a one-off payment

- Committing to reduce direct dependency over time.

Influencing consumer behaviour

Businesses, particularly retailers, are in a strong position to influence consumers by highlighting issues that producers face and advocating for sustainable practices. Buying ethical or fairly traded goods is one of the most effective ways for consumers to support sustainability – businesses can encourage this positive behaviour through:

- Honouring and advocating sustainable practices

- Community supply information

- Highlighting issues for producers.

Transparency

Impact and policy research on Fairtrade repeatedly highlights the lack of transparency in supply chains, particularly in pricing, contracts and the provision of market and producer information. This affects trading relationships and the ability of farmers and their organisations to participate in trade effectively. Businesses can commit to:

- Transparent communication of pricing and contracting terms

- Openness to exploring and negotiating all terms of contract and clarifying expectations clearly

- Providing market information on demand, supply, pricing and transfer of value in the chain

- Where possible, articulating long-term commitment to the relationship

- Encouraging farmer organisations to provide transparent information on all relevant transactions to members to encourage transparency and accountability along the chain.

Case Study: Liberation Foods – Cracking the issues around transparency

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to them allow us to process data such as browsing behaviour on this site.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Business resources and FAQs Fairtrade case studies Fairtrade expertise Fairtrade programmes Get in touch Sustainable sourcing with Fairtrade Thank you Why partner with Fairtrade Fairtrade Foundation, 5.7 The Loom, 14 Gower's Walk, London E1 8PY +44 (0)20 7405 5942 [email protected]

Fairtrade started more than 30 years ago to enable farmers and workers to have more control over their lives and invest in a sustainable future. Fairtrade certifies cocoa and other products that meet rigorous social, economic, and environmental standards, from farm to shelf. Farmers and workers benefit from Fairtrade's Minimum Price and Premium guarantees, as well as standards, training, and ...

A Beauty First. In 2022, e.l.f. and Fair Trade USA worked together to create a brand new framework for beauty industry factories to become Fair Trade Certified™, with e.l.f. being the first in the beauty industry to source from a Fair Trade Certified™ factory. The announcement of this certification was welcomed with enthusiasm as it demonstrates the range of products that can be Fair Trade ...

Impact Stories. Fairtrade is global. We work with nearly 2 million farmers and workers in the Global South and 2,400+ committed brands are selling Fairtrade certified products around the world.

Greggs case study: building back better with new Fairtrade commitments. Greggs are a long-standing and unique partner with Fairtrade in food-on-the-go retail. Greggs and Fairtrade: a success story on-the-go. The partnership started in 2006 when Greggs introduced Fairtrade coffee. It has since gone from strength to strength.

5.3. A case study from Fairtrade producers - the cotton industry. While Fairtrade operates for numerous agricultural and food products, including bananas, coffee, and chocolate, in this section we will focus on the cotton industry. As mentioned earlier, Fairtrade is an excellent example of a strategy that aims to address all three pillars of ...

Giuliano is among a growing group of coffee growers, roasters, and importers who believe that Fair Trade-certified coffee is not living up to its chief promise to reduce poverty.Retailers explain that neither FLO—the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International umbrella group—nor Fair Trade USA, the American standards and certification arm of FLO, has sufficient data showing positive ...

This case explores FT USA's market based approach and philosophy for increasing the reach and impact of Fair Trade. It reviews the concept of Fair Trade and the three pillars of the "Fair Trade for All" strategy: expand Fair Trade to include certification for large coffee growing estates and independent smaller farmers, invest in ...

Case Study: Matthew Algie and M&S - Brewing benefits with coffee farmers in Ethiopia . Case Study: Waitrose - Raising a cup to quality coffee in Brazil. Case Study: Palestinian Almonds - Creating a buzz about Palestinian Almonds. Case Study: A Programme Partnership to Create More Resilient Flower Supply Chains. Preferential sourcing

This case study focuses on the mass balance approach to traceability offered by Fairtrade International in addition to their offer of physical traceability. The case study comprises five sections. In section 2 we introduce the actor, Fairtrade International, and its role in the cocoa supply chain. In section 3 we describe the Fairtrade